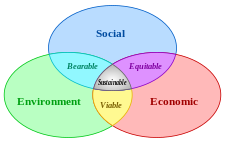

Environmental governance is a concept in political ecology and environmental policy that advocates sustainability as the supreme consideration for managing all human activities—political, social and economic.[1] Governance includes government, business and civil society, and emphasizes whole system management. To capture this diverse range of elements, environmental governance often employs alternative systems of governance, for example watershed-based management.[2]

It views natural resources and the environment as global public goods, belonging to the category of goods that are not diminished when they are shared.[3] This means that everyone benefits from for example, a breathable atmosphere, stable climate and stable biodiversity.

Public goods are non-rivalrous—a natural resource enjoyed by one person can still be enjoyed by others—and non-excludable—it is impossible to prevent someone consuming the good (breathing). Nevertheless, public goods are recognized as beneficial and therefore have value. The notion of a global public good thus emerges, with a slight distinction: it covers necessities that must not be destroyed by one person or state.

The non-rivalrous character of such goods calls for a management approach that restricts public and private actors from damaging them. One approach is to attribute an economic value to the resource. Water is possibly the best example of this type of good.

As of 2013 environmental governance is far from meeting these imperatives. “Despite a great awareness of environmental questions from developed and developing countries, there is environmental degradation and the appearance of new environmental problems. This situation is caused by the parlous state of global environmental governance, wherein current global environmental governance is unable to address environmental issues due to many factors. These include fragmented governance within the United Nations, lack of involvement from financial institutions, proliferation of environmental agreements often in conflict with trade measures; all these various problems disturb the proper functioning of global environmental governance. Moreover, divisions among northern countries and the persistent gap between developed and developing countries also have to be taken into account to comprehend the institutional failures of the current global environmental governance."

Contents

[hide]- 1 Definitions

- 2 Environmental issues

- 3 Environmental governance issues

- 4 Agreements

- 5 Background

- 6 Actors

- 6.1 International institutions

- 6.1.1 United Nations Environment Program

- 6.1.2 Global Environment Facility (GEF)

- 6.1.3 United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD)

- 6.1.4 World Environment Organization (WEO)

- 6.1.5 World Bank

- 6.1.6 World Trade Organization (WTO)

- 6.1.7 International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- 6.1.8 UN ICLEI

- 6.1.9 Other secretariats

- 6.1.10 Criticism

- 6.2 States

- 6.3 Business

- 6.4 Non-governmental organizations

- 6.1 International institutions

- 7 Proposals

- 8 Research groups

- 9 See also

- 10 References

Definitions[edit]

Environmental governance has been severally defined as: i) “the whole range of rules, practices and institutions related to the management of the environment in its different forms (conservation, protection, exploitation of natural resources, etc.)”;[4] ii) “all the processes and institutions, both formal and informal, that encompass the standards, values, behaviour and organizing mechanisms used by citizens, organizations and social movements as well as the different interest groups as a basis for linking up their interests, defending their differences and exercising their rights and obligations in terms of accessing and using natural resources.”;[5] and iii) "the formal and informal institutions, rules, mechanisms and processes of collective decision-making that enable stakeholders to influence and coordinate their interdependent needs and interests and their interactions with the environment at the relevant scales." [6]At the international level, global environmental governance is “the sum of organizations, policy instruments, financing mechanisms, rules, procedures and norms that regulate the processes of global environmental protection.” [7]

Key principles of environmental governance include:

- Embedding the environment in all levels of decision-making and action

- Conceptualizing cities and communities, economic and political life as a subset of the environment

- Emphasizing the connection of people to the ecosystems in which they live

- Promoting the transition from open-loop/craddle-to-grave systems (like garbage disposal with no recycling) to closed-loop/cradle-to-cradle systems (like permaculture and zero waste strategies).

There has been a growing interest in the effects of neoliberalism on the politics of the non-human world of environmental governance. Neoliberalism is seen to be more than a homogenous and monolithic ‘thing’ with a clear end point.[11] It is a series of path-dependent, spatially and temporally “connected neoliberalisation” processes which affect and are affected by nature and environment that “cover a remarkable array of places, regions and countries”.[12] Co-opting neoliberal ideas of the importance of private property and the protection of individual (investor) rights, into environmental governance can be seen in the example of recent multilateral trade agreements (see in particular the North American Free Trade Agreement). Such neoliberal structures further reinforce a process of nature enclosure and primitive accumulation or “accumulation by dispossession” that serves to privatise increasing areas of nature.[13] The ownership-transfer of resources traditionally not privately owned to free market mechanisms is believed to deliver greater efficiency and optimal return on investment.[14] Other similar examples of neo-liberal inspired projects include the enclosure of minerals, the fisheries quota system in the North Pacific[15] and the privatisation of water supply and sewage treatment in England and Wales.[16] All three examples share neoliberal characteristics to “deploy markets as the solution to environmental problems” in which scarce natural resources are commercialized and turned into commodities.[17] The approach to frame the ecosystem in the context of a price-able commodity is also present in the work of neoliberal geographers who subject nature to price and supply/demand mechanisms where the earth is considered to be a quantifiable resource (Costanza, for example, estimates the earth ecosystem's service value to be between 16 and 54 trillion dollars per year[18] ).

Environmental issues[edit]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

Factors resulting in environmental degradation[edit]

Economic growth – The development-centric vision that prevails in most countries and international institutions advocates a headlong rush towards more development, whereby the development of increasingly advanced technologies and more efficiently scaled economies would help to protect the environment against the damage caused by the very same development. Environmental economists, on the other hand, point to a close correlation between economic growth and environmental degradation, arguing for qualitative development as an alternative to growth. There are those, particularly within the alternative globalization movement, who maintain that it is feasible to change to a degrowth phase without losing social efficiency or lowering the quality of life.Consumption – The growth of consumption and the cult of consumption, or consumerist ideology, is the major cause of economic growth. Overdevelopment, seen as the only alternative to poverty, has become an end in itself. The means for curbing this growth are not equal to the task, since the phenomenon is not confined to a growing middle class in developing countries, but also concerns the development of irresponsible lifestyles, particularly in northern countries, such as the increase in the size and number of homes and cars per person.

Destruction of biodiversity – The complexity of the planet’s ecosystems means that the loss of any species has unexpected consequences. The stronger the impact on biodiversity, the stronger the likelihood of a chain reaction with unpredictable negative effects. Despite all the damage inflicted, a number of ecosystems have proved to be hugely resilient. Environmentalists are endorsing a precautionary principle whereby all potentially damaging activities would have to be analyzed for their environmental impact.

Population – Forecasts predict 8.9 billion people on the planet in 2050, representing an increase of 41% from current numbers. This is a subject which primarily affects developing countries, but also concerns northern countries; although their demographic growth is lower, the environmental impact per person is far higher in these countries. Demographic growth needs to be countered by developing education and family planning programmes and generally improving women’s status.

Challenges[edit]

The crisis caused by the impact of human activities on nature calls for responses by international institutions, governments and citizens. Governance intends to meet this crisis by pooling the experience and knowledge of each of the agents and institutions concerned.Environmental problems of climate change, biodiversity loss and degradation of ecosystem services threaten to block solutions and already restrict economic development in many countries and regions. Environmental protection measures remain insufficient. The necessary reforms require time, energy, money and diplomatic negotiations. The situation has not generated a unanimous response. Persistent divisions slow progress towards global environmental governance.

The global nature of the crisis limits the effects of national or sectoral measures. Cooperation is necessary between actors and institutions in international trade, sustainable development and peace.

Global, continental, national and local governments have employed a variety of approaches to environmental governance. Substantial positive and negative spillovers limit the ability of any single jurisdiction to resolve issues.

Challenges facing environmental governance include:

- Inadequate continental and global agreements

- Unresolved tensions between maximum development, sustainable development and maximum protection, limiting funding, damaging links with the economy and limiting application of Multilateral Environment Agreements (MEAs).

- Environmental funding is not self-sustaining, diverting resources from problem-solving into funding battles.

- Lack of integration of sector policies

- Inadequate institutional capacities

- Ill-defined priorities

- Unclear objectives

- Lack of coordination within the UN, governments, the private sector and civil society

- Lack of shared vision

- Interdependencies among development/sustainable economic growth, trade, agriculture, health, peace and security.

- International imbalance between environmental governance and trade and finance programs, e.g., World Trade Organization (WTO).

- Limited credit for organizations running projects within the Global Environment Facility (GEF)

- Linking UNEP, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank with MEAs

- Lack of government capacity to satisfy MEA obligations

- Absence of the gender perspective and equity in environmental governance

- Inability to influence public opinion[19][20][21]

TheAgenda 21 programme has been implemented in over 7,000 communities.[22] Environmental problems, including global-scale problems, may not require global solutions. For example, marine pollution can be tackled regionally, and ecosystem deterioration can be addressed locally. Other global problems such as climate change benefit from local and regional action.

Bäckstrand and Saward wrote, “sustainability and environmental protection is an arena in which innovative experiments with new hybrid, plurilateral forms of governance, along with the incorporation of a transnational civil society spanning the public-private divide, are taking place.” [23]

Local governance[edit]

The terms “participative” or “decentralized environmental governance” apply when decision-making shifts to the grassroots. Pulgar Vidal observed a “new institutional framework, [wherein] decision-making regarding access to and use of natural resources has become increasingly decentralized.” [24] He noted four techniques that can be used to develop these processes:- formal and informal regulations, procedures and processes, such as consultations and participative democracy;

- social interaction that can arise from participation in development programmes or from the reaction to perceived injustice;

- regulating social behaviours to reclassify an individual question as a public matter;

- within-group participation in decision-making and relations with external actors.

- access to social capital, including local knowledge, leaders and local shared vision;

- democratic access to information and decision-making;

- local government activity in environmental governance: as facilitator of access to natural resources, or as policy maker;

- an institutional framework that favours decentralized environmental governance and creates forums for social interaction and making widely-accepted agreements acceptable.[24]

State governance[edit]

At the state level, environmental management has been found to be conducive to the creation of roundtables and committees. In France, the Grenelle de l’environnement [26] process:- included a variety of actors (e.g. the state, political leaders, unions, businesses, not-for-profit organizations and environmental protection foundations);

- allowed stakeholders to interact with the legislative and executive powers in office as indispensable advisors;

- worked to integrate other institutions, particularly the Economic and Social Council, to form a pressure group that participated in the process for creating an environmental governance model;

- attempted to link with environmental management at regional and local levels.

“In southern countries, the main obstacle to the integration of intermediate levels in the process of territorial environmental governance development is often the dominance of developmentalist inertia in states’ political mindset. The question of the environment has not been effectively integrated in national development planning and programmes. Instead, the most common idea is that environmental protection curbs economic and social development, an idea encouraged by the frenzy for exporting raw materials extracted using destructive methods that consume resources and fail to generate any added value.” [28] Citizens in some states have responded by developing empowerment strategies to ease poverty through sustainable development.

Issues of scale[edit]

Multi-tier governance[edit]

The literature on governance scale shows how changes in the understanding of environmental issues have led to the movement from a local view to recognising their larger and more complicated scale. This move brought an increase in the diversity, specificity and complexity of initiatives. Meadowcroft pointed out innovations that were layered on top of existing structures and processes, instead of replacing them.[29]Lafferty and Meadowcroft give three examples: internationalisation, increasingly comprehensive approaches and involvement of multiple governmental entities.[30] Lafferty and Meadowcroft described the resulting multi-tiered system, addressing issues on both smaller and wider scales.

Institutional fit[edit]

Hans Bruyninckx claimed that a mismatch between the scale of the environmental problem and the level of the policy intervention was problematic.[31] Young claimed that such mismatches reduced the effectiveness of interventions.[32] Most of the literature addresses the level of governance rather than ecological scale.Elinor Ostrom, amongst others, claimed that the mismatch is often the cause of unsustainable management practices and that simple solutions to the mismatch have not been identified.[33][34]

Considerable debate has addressed the question of which level(s) should take responsibility for fresh water management. Development workers tend to address the problem at the local level. National governments focus on policy issues.[35] This can create conflicts among states because rivers cross borders, leading to efforts to evolve governance of river basins.[36]

Environmental governance issues[edit]

Soil deterioration[edit]

Soil and land deterioration reduces its capacity for capturing, storing and recycling water, energy and food. Alliance 21 proposed solutions in the following domains:[37]- include soil rehabilitation as part of conventional and popular education

- involve all stakeholders, including policymakers and authorities, producers and land users, the scientific community and civil society to manage incentives and enforce regulations and laws

- establish a set of binding rules, such as an international convention

- set up mechanisms and incentives to facilitate transformations

- gather and share knowledge;

- mobilize funds nationally and internationally

Climate change[edit]

The goal of combating climate change led to the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol by 191 states, an agreement encouraging the reduction of greenhouse gases, mainly CO2. Since developed economies produce more emissions per capita, limiting emissions in all countries inhibits opportunities for emerging economies, the only major success in efforts to produce a global response to the phenomenon.Two decades following the Brundtland Report, however, there has been no improvement in the key indicators highlighted.

Biodiversity[edit]

The 20th century witnessed accelerating biodiversity destruction. Estimates of extinction rates vary between a few and 200 species lost every day.The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was signed in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 human activities. The CBD’s objectives are: “to conserve biological diversity, to use biological diversity in a sustainable fashion, to share the benefits of biological diversity fairly and equitably.” The Convention is the first global agreement to address all aspects of biodiversity: genetic resources, species and ecosystems. It recognizes, for the first time, that the conservation of biological diversity is “a common concern for all humanity”. The Convention encourages joint efforts on measures for scientific and technological cooperation, access to genetic resources and the transfer of clean environmental technologies.

Water[edit]

The 2003 UN World Water Development Report claimed that the amount of water available over the next twenty years would drop by 30%.| This article is outdated. (September 2013) |

According to Alliance 21[38] “All levels of water supply management are necessary and independent. The integrated approach to the catchment areas must take into account the needs of irrigation and those of towns, jointly and not separately as is often seen to be the case....The governance of a water supply must be guided by the principles of sustainable development.”

Ozone layer[edit]

On 16 September 1987 the United Nations General Assembly signed the Montreal Protocol to address the declining ozone layer. Since that time, the use of chlorofluorocarbons (industrial refrigerants and aerosols) and farming fungicides such as methyl bromide has mostly been eliminated, although other damaging gases are still in use.Nuclear risk[edit]

The Nuclear non-proliferation treaty is the primary multilateral agreement governing nuclear activity.Transgenic organisms[edit]

Genetically modified organisms are not the subject of any major multilateral agreements. They are the subject of various restrictions at other levels of governance. GMOs are in widespread use in the US, but are heavily restricted in many other jurisdictions.Controversies have ensued over golden rice, genetically-modified salmon, genetically-modified seeds, disclosure and other topics.

Precautionary principle[edit]

The precautionary principle or precautionary approach states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the publicor to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus that the action or policy is harmful, the burden of proof that it is notharmful falls on those taking an action. As of 2013 it was not the basis of major multilateral agreements.Agreements[edit]

Conventions[edit]

The main multilateral conventions, also known as Rio Conventions, are as follows:Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (1992–1993): aims to conserve biodiversity. Related agreements include the Cartagena Protocol on biosafety.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) (1992–1994): aims to stabilize concentrations of greenhouse gases at a level that would stabilize the climate system without threatening food production, and enabling the pursuit of sustainable economic development; it incorporates the Kyoto Protocol.

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) (1994–1996): aims to combat desertification and mitigate the effects of drought and desertification, particularly in Africa.

Further conventions:

- Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (1971–1975)

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention (1972–1975)

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) (1973–1975)

- Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (1979–1983)

- Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention) (1992–1996)

- Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (1989–1992)

- Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedures for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (COP) (2001–2004)

- obligatory execution by signatory states

- involvement in a sector of global environmental governance

- focus on the fighting poverty and the development of sustainable living conditions;

- funding from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) for countries with few financial resources;

- inclusion of a for assessing ecosystem status[39]

- rigidity and verticality: they are too descriptive, homogenous and top down, not reflecting the diversity and complexity of environmental issues. Signatory countries struggle to translate objectives into concrete form and incorporate them consistently;

- duplicate structures and aid: the sector-specific format of the conventions produced duplicate structures and procedures. Inadequate cooperation between government ministries;

- contradictions and incompatibility: e.g., “if reforestation projects to reduce CO2 give preference to monocultures of exotic species, this can have a negative impact on biodiversity (whereas natural regeneration can strengthen both biodiversity and the conditions needed for life).” [19]

Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs)[edit]

MEAs are agreements between several countries that apply internationally or regionally and concern a variety of environmental questions. As of 2013 over 500 Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs), including 45 of global scope involve at least 72 signatory countries.[41] Further agreements cover regional environmental problems, such as deforestation in Borneo or pollution in the Mediterranean. Each agreement has a specific mission and objectives ratified by multiple states.“The environmental governance structure defined by the Rio and Johannesburg Summits is sustained by UNEP, MEAs and developmental organizations and consists of assessment and policy development, as well as project implementation at the country level.

"The governance structure consists of a chain of phases:

- a) assessment of environment status;

- b) international policy development;

- c) formulation of MEAs;

- d) policy implementation;

- e) policy assessment;

- f) enforcement;

- g) sustainable development.

Lack of coordination affects the development of coherent governance. The report shows that donor states support development organizations, according to their individual interests. They do not follow a joint plan, resulting in overlaps and duplication. MEAs tend not to become a joint frame of reference and therefore receive little financial support. States and organizations emphasize existing regulations rather than improving and adapting them.[41]

Background[edit]

The risks associated with nuclear fission raised global awareness of environmental threats. The 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty prohibiting atmospheric nuclear testing was the beginning of the globalization of environmental issues. Environmental law began to be modernized and coordinated with the Stockholm Conference (1972), backed up in 1980 by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.[42] The Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer was signed and ratified in 1985. In 1987, 24 countries signed the Montreal Protocol which imposed the gradual withdrawal of CFCs.The Brundtland Report, published in 1987 by the UN Commission on Environment and Development, stipulated the need for economic development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the capacity of future generations to meet their needs.

Rio Conference (1992) and reactions[edit]

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), better known as the 1992 Earth Summit, was the first major international meeting since the end of the Cold War and was attended by delegations from 175 countries. Since then the biggest international conferences that take place every 10 years guided the global governance process with a series of MEAs. Environmental treaties are applied with the help of secretariats.Governments created international treaties in the 1990s to check global threats to the environment. These treaties are far more restrictive than global protocols and set out to change non-sustainable production and consumption models.[43]

Agenda 21[edit]

Agenda 21 is a detailed plan of actions to be implemented at the global, national and local levels by UN organizations, member states and key individual groups in all regions. Agenda 21 advocates making sustainable development a legal principle law. At the local level, local Agenda 21 advocates an inclusive, territory-based strategic plan, incorporating sustainable environmental and social policies.The Agenda has been accused of using neoliberal principles, including free trade to achieve environmenal goals. For example, chapter two, entitled “International Cooperation to Accelerate Sustainable Development in Developing Countries and Related Domestic Policies” states, “The international economy should provide a supportive international climate for achieving environment and development goals by: promoting sustainable development through trade liberalization.”

Actors[edit]

International institutions[edit]

United Nations Environment Program[edit]

Main article: United Nations Environment Program

The UNEP has had its biggest impact as a monitoring and advisory body, and in developing environmental agreements. It has also contributed to strengthening the institutional capacity of environment ministries.In 2002 UNEP held a conference to focus on product lifecycle impacts, emphasizing the fashion, advertising, financial and retail industries, seen as key agents in promoting sustainable consumption.[43]

According to Ivanova, UNEP adds value in environmental monitoring, scientific assessment and information sharing, but cannot lead all environmental management processes. She proposed the following tasks for UNEP:

- initiate a strategic independent overhaul of its mission;

- consolidate the financial information and transparency process;

- restructure organizing governance by creating an operative executive council that balances the omnipresence of the overly imposing and fairly ineffectual Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum (GMEF).

Sherman proposed principles to strengthen UNEP:

- obtain a social consensus on a long-term vision;

- analyze the current situation and future scenarios;

- produce a comprehensive plan covering all aspects of sustainable development;

- build on existing strategies and processes;

- multiply links between national and local strategies;

- include all these points in the financial and budget plan;

- adopt fast controls to improve process piloting and identification of progress made;

- implement effective participation mechanisms.[45]

Global Environment Facility (GEF)[edit]

Main article: Global Environment Facility

Created in 1991, the Global Environment Facility is an independent financial organization initiated by donor governments including Germany and France. It was the first financial organization dedicated to the environment at the global level. As of 2013 it had 179 members. Donations are used for projects covering biodiversity, climate change, international waters, destruction of the ozone layer, soil degradation and persistent organic pollutants.GEF's institutional structure includes UNEP, UNDP and the World Bank. It is the funding mechanism for the four environmental conventions: climate change, biodiversity, persistent organic pollutants and desertification. GEF transfers resources from developed countries to developing countries to fund UNDP, UNEP and World Bank projects. The World Bank manages the annual budget of US$561.10 million.[47]

The GEF has been criticized for its historic links with the World Bank, at least during its first phase during the 1990s,[48] and for having favoured certain regions to the detriment of others.[49] Another view sees it as contributing to the emergence of a global "green market". It represents “an adaptation (of the World Bank) to this emerging world order, as a response to the emergence of environmental movements that are becoming a geopolitical force.”[50] Developing countries demanded financial transfers to help them protect their environment.

GEF is subject to economic profitability criteria, as is the case for all the conventions. It received more funds in its first three years than the UNEP has since its creation in 1972. GEF funding represents less than 1% of development aid between 1992 and 2002.[50]

United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD)[edit]

Main article: Commission on Sustainable Development

This intergovernmental institution meets twice a year to assess follow-up on Rio Summit goals. The CSD is made up of 53 member states, elected every three years and was reformed in 2004 to help improve implementation of Agenda 21. It meets twice a year, focusing on a specific theme during each two-year period: 2004-2005 was dedicated to water and 2006-2007 to climate change. The CSD has been criticized for its low impact, general lack of presence and the absence of Agenda 21 at the state level specifically, according to a report by the World Resources Institute.[51] Its mission focuses on sequencing actions and establishing agreements puts it in conflict with institutions such as UNEP and OECD.[7]World Environment Organization (WEO)[edit]

Main article: United Nations Environment Organization

A proposed World Environment Organization, analogous to the World Health Organization could be capable of adapting treaties and enforcing international standards.[52]The European Union, particularly France and Germany, and a number of NGOs favour creating a WEO. The United Kingdom, the USA and most developing countries prefer to focus on voluntary initiatives.[53] WEO partisans maintain that it could offer better political leadership, improved legitimacy and more efficient coordination. Its detractors argue that existing institutions and missions already provide appropriate environmental governance; however the lack of coherence and coordination between them and the absence of clear division of responsibilities prevents them from greater effectiveness.[40][20]

World Bank[edit]

Main article: World Bank

The World Bank influences environmental governance through other actors, particularly the GEF. The World Bank’s mandate is not sufficiently defined in terms of environmental governance despite the fact that it is included in its mission. However, it allocates 5 to 10% of its annual funds to environmental projects. The institution's capitalist vocation means that its investment is concentrated solely in areas which are profitable in terms of cost benefits, such as climate change action and ozone layer protection, whilst neglecting other such as adapting to climate change and desertification. Its financial autonomy means that it can make its influence felt indirectly on the creation of standards, and on international and regional negotiations.[54]Following intense criticism in the 1980s for its support for destructive projects which, amongst other consequences, caused deforestation of tropical forests, the World Bank drew up its own environment-related standards in the 1990s so it could correct its actions. These standards differ from UNEP’s standards, meant to be the benchmark, thus discrediting the institution and sowing disorder and conflict in the world of environmental governance. Other financial institutions, regional development banks and the private sector also drew up their own standards. Criticism is not directed at the World Bank’s standards in themselves, which Najam considered as “robust”,[7] but at their legitimacy and efficacy.

GEF[edit]

The GEF's account of itself as of 2012 [5] is as "the largest public funder of projects to improve the global environment", period, which "provides grants for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, international waters, land degradation, the ozone layer, and persistent organic pollutants." It claims to have provided "$10.5 billion in grants and leveraging $51 billion in co-financing for over 2,700 projects in over 165 countries [and] made more than 14,000 small grants directly to civil society and community based organizations, totaling $634 million." It serves as mechanism for the:- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

- Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD)

- implementation of Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer in some countries with "economies in transition" [6]

World Trade Organization (WTO)[edit]

Main article: World Trade Organization

The WTO’s mandate does not include a specific principle on the environment. All the problems linked to the environment are treated in such a way as to give priority to trade requirements and the principles of the WTO’s own trade system. This produces conflictual situations. Even if the WTO recognizes the existence of MEAs, it denounces the fact that around 20 MEAs are in conflict with the WTO’s trade regulations. Furthermore, certain MEAs can allow a country to ban or limit trade in certain products if they do not satisfy established environmental protection requirements. In these circumstances, if one country’s ban relating to another country concerns two signatories of the same MEA, the principles of the treaty can be used to resolve the disagreement, whereas if the country affected by the trade ban with another country has not signed the agreement, the WTO demands that the dispute be resolved using the WTO’s trade principles, in other words, without taking into account the environmental consequences.Some criticisms of the WTO mechanisms may be too broad. In a recently dispute over labelling of dolphin safe labels for tuna between the US and Mexico, the ruling was relatively narrow and did not, as some critics claimed,

International Monetary Fund (IMF)[edit]

Main article: International Monetary Fund

The IMF’s mission is to encourage growth and development. The IMF advocates reduced public expenditure, increased exports and foreign investment. The environment is not a priority for the IMF, leading it to favor projects that may have negative environmental effects.[citation needed]The IMF Green Fund proposal of Dominique Strauss-Kahn[55] specifically to address "climate-related shocks in Africa",[56] despite receiving serious attention[57] was rejected.[58] Strauss-Kahn's proposal, backed by France and Britain, was that "developed countries would make an initial capital injection into the fund using some of the $176 billion worth of SDR allocations from last year in exchange for a stake in the green fund." However, "most of the 24 directors ... told Strauss-Kahn that climate was not part of the IMF's mandate and that SDR allocations are a reserve asset never intended for development issues."[58]

UN ICLEI[edit]

The UN's main body for coordinating municipal and urban decision-making[59] is named the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives. Its slogan is "Local Governments for Sustainability". This body sponsored the concept of full cost accounting that makes environmental governance the foundation of other governance.ICLEIs projects and achievements include:

- Convincing thousands of municipal leaders to sign the World Mayors and Municipal Leaders Declaration on Climate Change (2005) which notably requests of other levels of government that:

- Global trade regimes, credits and banking reserve rules be reformed to advance debt relief and incentives to implement polices and practices that reduce and mitigate climate change.[60]

- Starting national councils to implement this and other key agreements, e.g., ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability USA

- Spreading ecoBudget (2008) [61] and Triple Bottom Line (2007) "tools for embedding sustainability into council operations",[62] e.g. Guntur's Municipal Corporation, one of the first four to ipmlement the entire framework.

- Sustainability Planning Toolkit (launched 2009)[63] integrating these and other tools

- Cities Climate Registry (launched 2010)[64] - part of UNEP Campaign on Cities and Climate Change[65]

Other secretariats[edit]

Other international institutions incorporate environmental governance in their action plans, including:- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), promoting development;

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO) which works on the climate and atmosphere;

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) working on the protection of agriculture, forests and fishing;

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) which focuses on nuclear security.

Criticism[edit]

According to Bauer, Busch and Siebenhüner,[66] the different conventions and multilateral agreements of global environmental regulation is increasing their secretariats' influence. Influence varies according to bureaucratic and leadership efficiency, choice of technical or client-centered.The United Nations is often the target of criticism, including from within over the multiplication of secretariats due to the chaos it produces. Using a separate secretariat for each MEA creates enormous overhead given the 45 international-scale and over 500 other agreements.

States[edit]

Environmental governance at the state level[edit]

Environmental protection has created opportunities for mutual and collective monitoring among neighbouring states. The European Union provides an example of the institutionalization of joint regional and state environmental governance. Key areas include information, led by the European Environment Agency (EEA), and the production and monitoring of norms by states or local institutions.State participation in global environmental governance[edit]

US refusal to ratify major environment agreements produced tensions with ratifiers in Europe and Japan.The World Bank, IMF and other institutions are dominated by the developed countries and do not always properly consider the requirements of developing countries.

Business[edit]

Environmental governance applies to business as well as government. Considerations are typical of those in other domains:- values (vision, mission, principles);

- policy (strategy, objectives, targets);

- oversight (responsibility, direction, training, communication);

- process (management systems, initiatives, internal control, monitoring and review, stakeholder dialogue, transparency, environmental accounting, reporting and verification);

- performance (performance indicators, benchmarking, eco-efficiency, reputation, compliance, liabilities, business development).[67]

Business environmental issues include emissions, biodiversity, historical liabilities, product and material waste/recycling, energy use/supply and many others.[67]

Environmental governance has become linked to traditional corporate governance as an increasing number of shareholders are corporate environmental impacts.[68] Corporate governance is the set of processes, customs, policies, laws, and institutions affecting the way a corporation (or company) is managed. Corporate governance is affected by the relationships among stakeholders. These stakeholders research and quantify performance to compare and contrast the environmental performance of thousands of companies.[69]

Large corporations with global supply chains evaluate the environmental performance of business partners and suppliers for marketing and ethical reasons. Some consumers seek environmentally friendly and sustainable products and companies.

Non-governmental organizations[edit]

Main article: Non-governmental organizations

According to Bäckstrand and Saward,[23] “broader participation by non-state actors in multilateral environmental decisions (in varied roles such as agenda setting, campaigning, lobbying, consultation, monitoring, and implementation) enhances the democratic legitimacy of environmental governance.”Local activism is capable of gaining the support of the people and authorities to combat environmental degradatation. In Cotacachi, Ecuador, a social movement used a combination of education, direct action, the influence of local public authorities and denunciation of the mining company’s plans in its own country, Canada, and the support of international environmental groups to influence mining activity.[70]

Fisher cites cases in which multiple strategies were used to effect change.[71] She describes civil society groups that pressure international institutions and also organize local events. Local groups can take responsibility for environmental governance in place of governments.[72][73]

According to Bengoa,[74] “social movements have contributed decisively to the creation of an institutional platform wherein the fight against poverty and exclusion has become an inescapable benchmark.” But despite successes in this area, “these institutional changes have not produced the processes for transformation that could have made substantial changes to the opportunities available to rural inhabitants, particularly the poorest and those excluded from society.” He cites several reasons:

- conflict between in-group cohesion and openness to outside influence;

- limited trust between individuals;

- contradiction between social participation and innovation;

- criticisms without credible alternatives to environmentally damaging activities

Proposals[edit]

The International Institute for Sustainable Development proposed an agenda for global governance. These objectives are:[7]- expert leadership;

- positioning science as the authoritative basis of sound environmental policy;

- coherence and reasonable coordination;

- well-managed institutions;

- incorporate environmental concerns and actions within other areas of international policy and action

Coherence and coordination[edit]

Inforesources[75] identifies four major obstacles to global environmental governance, and describes measures in response. The four obstacles are:- parallel structures and competition, without a coherent strategy

- contradictions and incompatibilities, without appropriate compromise

- competition between multiple agreements with incompatible objectives, regulations and processes

- integrating policy from macro- to micro- scales.

- MDGs

and conventions, combining sustainbility and reduction of poverty and equity;

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2013) - country-level approach linking global and local scales

- coordination and division of tasks in a multilateral approach that supports developing countries and improves coordination between donor countries and institutions

- use of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) in development planning

- transform conflicts into tradeoffs, synergies and win-win options

Democratization[edit]

Starting in 2002, Saward[23] and others began to view the Earth Summit process as capable opening up the possibility of stakeholder democracy. The summits were deliberative rather than simply participative, with NGOs, women, men, indigenous peoples and businesses joining the decision-making process alongside states and international organizations, characterized by:- the importance given to scientific and technical considerations

- the official and unofficial participation of many actors with heterogeneous activity scopes

- growing uncertainty

- a new interpretation of international law and social organization models[76]

Institutional reform[edit]

Actors inside and outside the United Nations are discussing possibilities for global environmental governance that provides a solution to current problems of fragility, coordination and coherence.[78] Deliberation is focusing on the goal of making UNEP more efficient. A 2005 resolution recognizes “the need for more efficient environmental activities in the United Nations system, with enhanced coordination, improved policy advice and guidance, strengthened scientific knowledge, assessment and cooperation, better treaty compliance, while respecting the legal autonomy of the treaties, and better integration of environmental activities in the broader sustainable development framework.”Proposals include:[79]

- greater and better coordination between agencies;

- strengthen and acknowledge UNEP’s scientific role;

- identify MEA areas to strengthen coordination, cooperation and team work between different agreements;

- increase regional presence;

- implement the Bali Strategic Plan on improving technology training and support for the application of environmental measures in poor countries;

- demand that UNEP and MEAs participate formally in all relevant WTO committees as observers.

- strengthen its financial situation;

- improve secretariats’ efficiency and effectiveness.

- clearly divide tasks between development organizations, UNEP and the MEAs

- adopt a political direction[clarification needed] for environmental protection and sustainable development

- authorize the UNEP Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum to adopt the UNEP medium-term strategy

- allow Member States to formulate and administer MEAs an independent secretariat for each convention

- support UNEP in periodically assessing MEAs and ensure coordination and coherence

- establish directives for setting up national/regional platforms capable of incorporating MEAs in the Common Country Assessment (CCA) process and United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF)[80]

- establish a global joint planning framework

- study the aptitude and efficiency of environmental activities’ funding, focusing on differential costs

- examine and redefine the concept of funding differential costs as applicable to existing financial mechanisms

- reconsider remits, division of tasks and responsibilities between entities that provide services to the multipartite conferences. Clearly define the services that UN offices provide to MEA secretariats

- propose measures aiming to improve personnel provision and geographic distribution for MEA secretariats

- improve transparency resource use for supporting programmes and in providing services to MEAs. Draw up a joint budget for services supplied to MEAs.

Education[edit]

A 2001 Alliance 21 report proposes six fields of action:[81]- strengthen citizens' critical faculties to ensure greater democratic control of political orientations

- develop a global and critical approach

- develop civic education training for teachers

- develop training for certain socio-professional groups

- develop environmental education for the entire population;

- assess the resulting experiences of civil society

Transform daily life[edit]

Individuals can modify consumption, based on voluntary simplicity: changes in purchasing habits, simplified lifestyles (less work, less consumption, more socialization and constructive leisure time). But individual actions must not replace vigilance and pressure on policies.[43] Notions of responsible consumption developed over decades, revealing the political nature of individual purchases, according to the principle that consumption should satisfy the population’s basic needs. These needs comprise the physical wellbeing of individuals and society, a healthy diet, access to drinking water and plumbing, education, healthcare and physical safety.[43] The general attitude centres on the need to reduce consumption and reuse and recycle materials. In the case of food consumption, local, organic and fair trade products which avoid ill treatment of animals has become a major trend.Alternatives to the personal automobile are increasing, including public transport, car sharing and bicycles and alternative propulsion systems.

Alternative energy sources are becoming less costly.

Ecological industrial processes turn the waste from one industry into raw materials for another.

Governments can reduce subsidies/increase taxes/tighten regulation on unsustainable activities.[43]

The Community Environmental governance Global Alliance encourages holistic approaches to environmental and economic challenges, incorporating indigenous knowledge.[82] Okotoks, Alberta capped population growth based on the carrying capacity of the Sheep River.[83] The Fraser Basin Council Watershed Governance[84] in British Columbia, Canada, manages issues that span municipal jurisdictions. Smart Growth is an international movement that employs key tenets of Environmental governance in urban planning.

Policies and regulations[edit]

Establish policies and regulations that promote “infrastructures for well being” whilst addressing the political, physical and cultural levels.Eliminate subsidies that have a negative environmental impact and tax pollution

Promoting workers’ personal and family development.[43]

Coordination[edit]

A programme of national workshops on synergies between the three Rio Conventions launched in late 2000, in collaboration with the relevant secretariats. The goal was to strengthen coordination at the local level by:- sharing information

- promoting political dialogue to obtain financial support and implement programmes

- enabling the secretariats to update their joint work programmes.[85]

Moving local decisions to the global level is as important as the way in which local initiatives and best practices are part of a global system. Kanie[87] points out that NGOs, scientists, international institutions and stakeholder partnerships can reduce the distance that separates the local and international levels.

Research groups[edit]

The POLIS Project on Environmental governance based out of the University of Victoria conducts research on environmental governance.[88]See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up ^ Page 8. The Soft Path in a Nutshell. (2005). Oliver M Brandes and David B Brooks. University of Victoria, Victoria, BC.

- Jump up ^ IPlanet U, R. Michael M'Gonigle, Justine Starke

- Jump up ^ Launay, Claire, Mouriès, Thomas, Les différentes catégories de biens , summary and excerpt from Pierre Calame’s book, ’’La démocratie en miettes’’, 2003.

- Jump up ^ Fontaine, Guillaume; Verde y negro: ecologismo y conflictos por petróleo en el Ecuador, (Green and Black: environmentalism and oil conflicts in Ecuador) in G. Fontaine, G. van Vliet, R. Pasquis (Coord.), “Políticas ambientales y gobernabilidad en América Latina" (Environmental policies and governance in Latin America); Quito: FLACSO-IDDRI-CIRAD, 2007, pp. 223-254

- Jump up ^ Ojeda, L.; Gobernabilidad en la Conservación de los Recursos Naturales (Governance of Natural Resources Conservation); Red ECOUF; Universidad de La Florida (draft); 2005

- Jump up ^ Tacconi, L. (2011). Developing environmental governance research: The example of forest cover change studies. Environmental Conservation, 38(2): 234-246.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Najam, A., Papa, M. and Taiyab, N. Global Environmental Governance. A Reform Agenda; IISD; 2006.

- Jump up ^ Castree, N. (2007) ‘Neoliberal ecologies’, in Nik Heynen, James McCarthy, Scott Prudham and Paul Robbins (eds.) Neoliberal environments, London: Routledge, p. 281.

- Jump up ^ Jessop B. (2002) ‘Liberalism, Neo-Liberalism and Urban Governance: A State Theoretical Perspective’, Antipode, 34 (3), p. 454.

- Jump up ^ Peck, J. and Tickell, A. (2002) ‘Neoliberalizing Space’, Antipode, 34(3): p. 382.

- Jump up ^ Heynen N and Robins P. (2005) ‘The neoliberalization of nature: Governance, privatization, enclosure and valuation’, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 16(1): p. 6.

- Jump up ^ Castree, N. (2007) ‘Neoliberal ecologies’, in Nik Heynen, James McCarthy, Scott Prudham and Paul Robbins (eds.) Neoliberal environments, London: Routledge, p. 283.

- Jump up ^ McCarthy, J. (2004) ‘Privatizing conditions of production: trade agreements as neoliberal environmental governance’, Geoforum, 35(3), p. 327.

- Jump up ^ Swyngedouw, E. (2005) ‘Dispossessing H20: The contested terrain of water privatisation’, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 16(1): pp. 1-18.

- Jump up ^ Mansfield, B. (2004) ‘Rules of Privatization: Contradictions in Neoliberal Regulation of North Pacific Fisheries’ Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 94(3): pp. 565–584.

- Jump up ^ Bakker, K. (2004) An uncooperative commodity: privatizing water in England and Wales, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Jump up ^ Bakker, K. (2004) An uncooperative commodity: privatizing water in England and Wales, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.431

- Jump up ^ Costanza, R. et al., (1997) ‘The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital’, Nature 387(6630): pp. 255

- ^ Jump up to: a b Global Conventions and Environmental Governance; Inforesources Focus No. 3, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b UNEP; International Environmental Governance and the Reform of the United Nations, XVI Meeting of the Forum of Environment Ministers of Latin America and the Caribbean; 2008.

- Jump up ^ Civil Society Statement on International Environmental Governance; Seventh special session of the UNEP Governing Council/GMEF; Cartagena, Colombia; February 2002.

- Jump up ^ 7,000 municipalities is very few, in view of the fact that over a million municipalities exist on the planet and that initial forecasts were for local agenda 21 actions being adopted in 500,000 municipalities in 1996 and throughout the rest of the planet in 2000

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bäckstrand, Karin; Saward, Michel; Democratizing Global Governance: Stakeholder Democracy at the World Summit for Sustainable Development; Document presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association; Chicago; 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pulgar Vidal, Manuel; Gobernanza Ambiental Descentralizada (Decentralized Environmental Governance); 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Suárez, David; Poats, Susan V.; Procesos de Gobernanza Ambiental en el Manejo Participativo de Áreas Protegidas en Carchi (Environmental Governance Processes in the Participative Management of Carchi Protected Areas); Symposium; 2008.

- Jump up ^ Operational Committee No. 24 "Institutions and stakeholder representativity" (introduced by Bertrand Pancher); Final report to the Prime Minister, senior Minister, Minister for the Ecology, Sustainable Development and Territorial Planning; 2008, also known as the Rapport Pancher.

- Jump up ^ Laime, Marc; Gouvernance environnementale: vers une meilleure concertation ? (Environmental Governance: towards better consultation?); 2008.

- Jump up ^ IUCN; Gobernanza ambiental para un desarrollo sostenible (Environmental Governance for Sustainable Development).

- Jump up ^ Meadowcroft, James (2002). "Politics and scale: some implications for environmental governance". landscape and urban planning 61: 169–179.

- Jump up ^ Lafferty, William; Meadowcroft, James (2000). Implementing Sustainable Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jump up ^ Bruyninckx, Hans (2009). "Environmental evaluation practices and the issue of scale". New directions for evaluation 122: 31–39.

- Jump up ^ Young, Oran (2006). "The globalization of socio-ecological systems: An agenda for scientific research". Global Environmental Change 16: 304–316.

- Jump up ^ Folke, C (2007). "The problem of fit between ecosystems and institutions: ten years later". Ecology and Society 12 (1): 30.

- Jump up ^ Ostrem, Elinor (2007). "A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States 104 (39): 15181–15187.

- Jump up ^ Lebel, L; Garden, L & Imamura, M (2005). "The Politics of Scale, Position and Place in the Governance of Water Resources in the Mekong Region". Ecology and Society 10 (2): 18.

- Jump up ^ Zagg, V; Gupta, J (2008). "Scale issues in the governance of water storage projects". Water Resouces Research 44.

- Jump up ^ Alliance 21’s Proposal Paper “Save our Soils to Sustain our Societies”

- Jump up ^ Proposals Related to the Water Issue

- Jump up ^ Millenium assessment

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kanie & Haas 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Inomata, Tadanori; Management Review of Environmental Governance within the United Nations System; United Nations; Joint Inspection Unit; Geneva; 2008.

- Jump up ^ Di Mento, Josep; The Global Environment and International law, University of Texas Press; 2003; p 7..

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Bouguerra, Larbi; La consommation assassine. Comment le mode de vie des uns ruine celui des autres, pistes pour u ne consommation responsible (Consumption Kills. How some people’s lifestyles ruin other people’s lives. Ideas for responsible consumption) ; Éditions Charles Léopold Mayer; 2005; adaptation of State of the World. Special Focus - The Consumer Society; The Worldwatch Institute; 2004.

- Jump up ^ Reforming International Environmental Governance: Statement representing views expressed at two meetings of stakeholders held at the 24th Session of the UNEP Governing Council/GMEF 2007.

- Jump up ^ Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future, et al (comp.); Options for Strengthening the Environment Pillar of Sustainable Development. Compilation of Civil Society Proposals on the Institutional Framework for the United Nations' Environmental Activities; 2007.

- Jump up ^ Submission by the Brazilian Forum of NGOs and Social Movements for the Environment and the Development to the Panel Consultation with Civil Society; June 2006.

- Jump up ^ Zoë, Young (2002). A new green order: The World Bank and the politics of the global environmental facility. London: Pluto Press.

- Jump up ^ Andler, Lydia; The Secretariat of the Global Environment Facility: From Network to Bureaucracy; "Global Governance Working Paper", no. 24; Amsterdam et al.; The Global Governance Project; 2007.

- Jump up ^ Werksman, Jake; Consolidating global environmental governance: New lessons from the GEF?; in Kanie & Haas 2004

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zoë2002, p. 3.

- Jump up ^ World Resources Institute; World Resources 2002–2004: Decisions for the Earth: Balance, Voice and Power; Washington DC; 2004.

- Jump up ^ proposals

- Jump up ^ Tubiana, L.; Martimort-Asso, B.; Gouvernance internationale de l'environnement: les prochaines étapes (International Environmental Governance; the next stages); in "Synthèse", 2005, no. 01, Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales (IDDRI).

- Jump up ^ Marschinski, Robert; Behrle, Steffen; The World Bank: Making the Business Case for the Environment; "Global Governance Working Paper No 21"; Amsterdam et al; The Global Governance Project; 2006.

- Jump up ^ "IMF Survey: IMF Proposes "Green Fund" for Climate Change Financing". Imf.org. 2010-01-30. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ Recio, Eugenia (2010-03-08). "IMF Chief Proposes Green Fund to Address Climate-Related Shocks in Africa - Climate Change Policy & Practice". Climate-l.iisd.org. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ "The IMF's Green Fund Proposal". Wdev.eu. 2010-02-04. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "IMF member countries reject green fund plan". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ [1]

- Jump up ^ [2][dead link]

- Jump up ^ [3][dead link]

- Jump up ^ [4][dead link]

- Jump up ^ ICLEI Releases Sustainability Toolkit (2009-12-05). "ICLEI Releases Sustainability Toolkit - Triple Bottom Line". Blog.accessfayetteville.org. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ "Mayors launch reporting platform of cities at Climate Summit | WMSC 2010 Mexico City | World Mayors Summit on Climate 2010". Wmsc2010.org. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ "Urban Environment Unit , UNEP". Unep.org. 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ Bauer, Steffen; Busch, Per-Olof; Siebenhüner, Bernd; Administering International Governance: What Role for Treaty Secretariats? "Global Governance Working Paper" No 29. Amsterdam et al; The Global Governance Project; 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c White, Andrew; Klernan, Matthew; Corporate Environment Governance. A Study into the Influence of Environmental Governance and the Financial Performance; Environment Agency (United Kingdom Government); 2004.

- Jump up ^ "Environmental Governance". Wallace Partners. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- Jump up ^ "Priority Stakeholders". Wallace Partners. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ Bebbington, Anthony; et al.; Los movimientos sociales frente a la minería: disputando el desarrollo territorial andino (Social Movements and Mining: disputes over territorial development in the Andes); in J. Bengoa (ed.) "Movimientos sociales y desarrollo territorial rural en América Latina" (Social Movements and Territorial Rural Development in Latin America). Catalonia; 2007.

- Jump up ^ Fisher, Dana R.; Civil Society Protest and Participation: Civic Engagement Within the Multilateral Governance Regime pp. 176-201; in Kanie & Haas 2004

- Jump up ^ "Community-Based Marine Conservation | The Nature Conservancy". Nature.org. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ Andrade Mendoza, Karen; La gobernanza ambiental en el Ecuador: El conflicto alrededor de la licencia Ambiental en el bloque 31, en el parque nacional Yasuní (Environmental Governance in Ecuador: the conflict concerning the environmental license for block 31 in the Yasuní National Park); FLACSO; Observatorio Socioambiental; Quito; 2008.

- Jump up ^ Bengoa, José; et al. Movimientos sociales, gobernanza ambiental y desarrollo territorial (Social Movements, Environmental Governance and Territorial Development) ; Catalonia; 2007.

- Jump up ^ Global Conventions and Environmental Governance

- Jump up ^ Behnassi, Mohamed; Les négociations environnementales multilatérales: Vers une gouvernance environnementale mondiale (Multilateral Environmental Negotiations: towards world environmental governance); doctoral thesis summary paper; Casablanca; 2003.

- Jump up ^ Johal, Surjinder; Ulph, Alistair; Globalization, Lobbying and International Environmental Governance; "Review of International Economics", 10, (3), 387-403; 2002.

- Jump up ^ Resolution 60/1 of the United Nations General Assembly.

- Jump up ^ UN environmental governance report

- Jump up ^ The CCA is the main diagnostic tool available for teams working in UN countries and their partners. It is used to assess and create a shared understanding of the underlying challenges facing a country during its development. The UNDAF is a product of the CCA analysis and collaboration process and provides the basis for UN cooperation programmes. (Source: ISDR; Words into Action: A Guide for Implementing the Hyogo Framework; United Nations; 2007; chapter 4; p. 81-120).

- Jump up ^ Ziaka, Yolanda; Robicon, Philippe; Souchon, Christian; Environmental Education: Six Proposals for Citizens’ Action. Proposal Paper, Alliance for a Responsible, Plural and United World; 2001.

- Jump up ^ Community Environmental governance Global Alliance (CEG-GA), The Gaia Foundation website, accessed November 18, 2009

- Jump up ^ "Okotoks - 1. Water Management". Okotoks.ca. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ "Fraser Basin Council - Home". Fraserbasin.bc.ca. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- Jump up ^ Diallo, Hama Arba; La gouvernance environnementale et la synergie entre les trois conventions globales (Environmental Governance and the Synergy between the Three Global Conventions); Johannesburg Summit document; 2002.

- Jump up ^ Campbell, Laura B.; The Effectiveness of WTO and WIPO: Lessons for Environmental Governance? in Kanie & Haas 2004

- Jump up ^ Kanie, Norichika; Global Environmental Governance in Terms of Vertical Linkages; pp. 86-113 Kanie & Haas 2004

- Jump up ^ "UVic Faculty of Law - University of Victoria". Law.uvic.ca. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

Sources[edit]

- Kanie, Norichika; Haas, Peter M. (2004). Emerging Forces in Environmental Governance. UNU Press.

- Forum for a New World Governance

- Lennart J. Lundqvist (2004), Sweden and Environmental governance: Straddling the Fence. Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-6902-5

| ||

| |||

No comments:

Post a Comment