May 20 2014 12:27 FT Alphaville

Ken Rogoff wades into the negative rate debate this month, in a paper that discusses the costs and benefits of phasing out paper currency — a topic previously explored by Willem Buiter and Miles Kimball (and of course Satoshi Nakamoto).

Among his observations is the somewhat provocative point (at least judging by the replies on Twitter) that…

That said, while Rogoff refers to Blanchard on that point, he ultimately concedes that negative rates may be much more effective in the long run:

In any case, this leads Rogoff to the dreaded subject of how best to substitute paper cash for electronic cash.

As Rogoff notes, the key problem is the uniquely anonymous nature of cash, something which facilitates tax evasion and illegal activity all round. Electronic money may be private but it’s certainly not anonymous (and that applies to Bitcoin as well).

As Rogoff further explains:

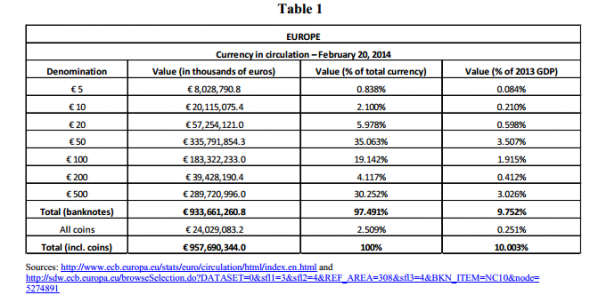

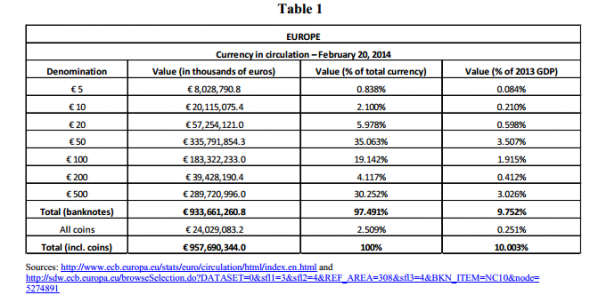

Here, for example, is a chart for the euro system:

To summarise:

The problem this poses for the public purse is that even though the substitution of paper cash for electronic cash should not theoretically affect seigniorage revenue for the government — because phased-out paper currency demand would be replaced by demand for electronic central bank reserves — the non-anonymous nature of electronic money would likely lead to a large shrinkage in demand.

In Rogoff’s opinion, Treasuries or other anonymous vehicles would have to absorb that loss instead.

The only caveat would be if the government managed to introduce a fully anonymous electronic money in its own right.

As he notes:

Rogoff says that might not be so bad if there were rules and protocols in place to ensure the government could not abuse its unique information advantage in that regard.

Nevertheless, none of this spares the country from the risk that another country’s paper currency might end up becoming used more commonly in the economy instead.

Overall, Rogoff concludes further study of the costs and benefits of phasing out paper currency is necessary, especially since we may already live in the “twilight of the paper currency era anyway”.

In any case, a few points we’re left confused about:

1) First, Rogoff claims that if there were concerns about anonymous digital central bank cash, people would likely park money in Treasuries instead and that this would reduce seigniorage income.

Surely, this thinking doesn’t make sense? Wouldn’t the money redirected from zero-yielding cash, which is provided by the government on demand (especially so that it is always zero yielding), be redirected into yielding securities in such a way that it would have negative yielding effects? If that’s the case the negative rates provided to the government would be a form of seigniorage revenue, and could be exploited by greater borrowing at zero rates.

2) Second, doesn’t Rogoff neglect the seigniorage revenue that’s already being lost — irrespective of anonymity — due to the shortage of safe assets problem? The market also has a preference for creating private money substitutes — whether they’re bearer notes collateralised by art, collateralised commodities in no-man’s land stores or bitcoin — rather than taking on more free debt. After all, the former currently allocates the money much more questionably than structured public policy might do.

3) Why has no-one yet made the connection between anonymity — which is injected into the system by means of anonymous bearer currency which “neither buyer nor seller requires knowledge of its history” — and our inability to model or control systemic risk?

All thoughts appreciated.

Among his observations is the somewhat provocative point (at least judging by the replies on Twitter) that…

Paying a negative interest rate on currency, or on electronic reserves at the central bank, may seem barbaric to some. But it is arguably no more barbaric than inflation, which similarly reduces the real purchasing power of currency.Meaning that a good bout of inflation could be just as good as a negative rate regime.

That said, while Rogoff refers to Blanchard on that point, he ultimately concedes that negative rates may be much more effective in the long run:

The idea of raising target inflation to reduce the likelihood of hitting the zero bound is indeed an alternative approach. Blanchard et al. point out that if central banks permanently raised their target inflation rates from 2% to 4%, it would leave them scope to make deeper cuts to real interest rates in severe downturns. Arguably, paying negative interest rates is a better approach if, as many believe, inflation becomes more unstable as the general level of inflation rises. Robert Hall (1983) argues forcefully that the central role of monetary policy should be to provide a stable unit of account, and in principle the ability to pay negative interest rates facilitates its ability to achieve this in today’s low inflation environment (Hall, 2002, 2012).(For further discussion about the Blanchard plan see here.)

In any case, this leads Rogoff to the dreaded subject of how best to substitute paper cash for electronic cash.

As Rogoff notes, the key problem is the uniquely anonymous nature of cash, something which facilitates tax evasion and illegal activity all round. Electronic money may be private but it’s certainly not anonymous (and that applies to Bitcoin as well).

As Rogoff further explains:

Standard monetary theory (e.g., Kiyotaki and Wright 1989) suggests that an essential property of money is that neither buyer nor seller requires knowledge of its history, giving it a certain form of anonymity. (A slight caveat is that the identity of the buyer might be correlated with the probability of the currency being counterfeit, but until now this is a problem that governments have been able to contain.) There is nothing, however, in standard theories of money that requires transactions to be anonymous from tax- or law-enforcement authorities. And yet there is a significant body of evidence that a large percentage of currency in most countries, generally well over 50%, is used precisely to hide transactions. I have summarized the international evidence in earlier research (Rogoff 1998, 2002). Other than the introduction of the euro, rather little has changed except that, if anything, anonymous currencies have continued to grow at a faster rate than nominal GDP.The most surprising thing about cash in that context is probably just how much of it there remains in circulation considering the efficiency of modern electronic systems.

Here, for example, is a chart for the euro system:

To summarise:

…in the US the currency supply is 7% of GDP, in the Eurozone 10%, and in Japan 18%.Which means, despite the fact that the use of currency in the legal economy is dwindling due to advances in cashless payments, the world still remains hopelessly addicted to cash for black economy reasons.

The problem this poses for the public purse is that even though the substitution of paper cash for electronic cash should not theoretically affect seigniorage revenue for the government — because phased-out paper currency demand would be replaced by demand for electronic central bank reserves — the non-anonymous nature of electronic money would likely lead to a large shrinkage in demand.

In Rogoff’s opinion, Treasuries or other anonymous vehicles would have to absorb that loss instead.

The only caveat would be if the government managed to introduce a fully anonymous electronic money in its own right.

As he notes:

The government would continue to garner seigniorage revenues from the underground economy and the problem of the zero bound on nominal interest rates would be effectively eliminated. That said, it is far from clear that the government can credibly issue a fully anonymous electronic currency and even if it could, anonymous electronic fiat money has all the drawbacks of an anonymous paper currency in facilitating tax evasion and illegal activity.Rogoff also suggests that any attempt to introduce a fully anonymous state currency would probably transform the central bank into a universal bank — something we’ve suggested is already happening due to the Fed already expanding its balance sheet to money market funds.

Rogoff says that might not be so bad if there were rules and protocols in place to ensure the government could not abuse its unique information advantage in that regard.

Nevertheless, none of this spares the country from the risk that another country’s paper currency might end up becoming used more commonly in the economy instead.

Overall, Rogoff concludes further study of the costs and benefits of phasing out paper currency is necessary, especially since we may already live in the “twilight of the paper currency era anyway”.

In any case, a few points we’re left confused about:

1) First, Rogoff claims that if there were concerns about anonymous digital central bank cash, people would likely park money in Treasuries instead and that this would reduce seigniorage income.

Surely, this thinking doesn’t make sense? Wouldn’t the money redirected from zero-yielding cash, which is provided by the government on demand (especially so that it is always zero yielding), be redirected into yielding securities in such a way that it would have negative yielding effects? If that’s the case the negative rates provided to the government would be a form of seigniorage revenue, and could be exploited by greater borrowing at zero rates.

2) Second, doesn’t Rogoff neglect the seigniorage revenue that’s already being lost — irrespective of anonymity — due to the shortage of safe assets problem? The market also has a preference for creating private money substitutes — whether they’re bearer notes collateralised by art, collateralised commodities in no-man’s land stores or bitcoin — rather than taking on more free debt. After all, the former currently allocates the money much more questionably than structured public policy might do.

3) Why has no-one yet made the connection between anonymity — which is injected into the system by means of anonymous bearer currency which “neither buyer nor seller requires knowledge of its history” — and our inability to model or control systemic risk?

All thoughts appreciated.

No comments:

Post a Comment