From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Buckminster fuller)

For the EP by Nerina Pallot, see Buckminster Fuller EP.

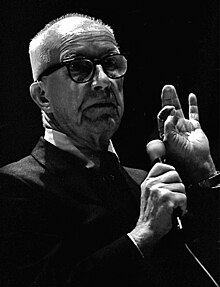

| Buckminster Fuller | |

|---|---|

Richard Buckminster Fuller | |

| Born | July 12, 1895 Milton, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | July 1, 1983 (aged 87) Los Angeles, United States |

| Occupation | Designer, author, inventor |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Hewlett (m. 1917) |

| Children | 2: Allegra Fuller Snyder and Alexandra who died in childhood |

Fuller published more than 30 books, inventing and popularizing terms such as "Spaceship Earth", ephemeralization, and synergetic. He also developed numerous inventions, mainly architectural designs, including the widely known geodesic dome. Carbon molecules known as fullerenes were later named by scientists for their resemblance to geodesic spheres.

Buckminster Fuller was the second president of Mensa from 1974 to 1983.[2]

Contents |

[edit] Biography

Fuller was born on July 12, 1895, in Milton, Massachusetts, the son of Richard Buckminster Fuller and Caroline Wolcott Andrews, and also the grandnephew of the American Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller. He attended Froebelian Kindergarten. Spending much of his youth on Bear Island, in Penobscot Bay off the coast of Maine, he had trouble with geometry, being unable to understand the abstraction necessary to imagine that a chalk dot on the blackboard represented a mathematical point, or that an imperfectly drawn line with an arrow on the end was meant to stretch off to infinity. He often made items from materials he brought home from the woods, and sometimes made his own tools. He experimented with designing a new apparatus for human propulsion of small boats.Years later, he decided that this sort of experience had provided him with not only an interest in design, but also a habit of being familiar with and knowledgeable about the materials that his later projects would require. Fuller earned a machinist's certification, and knew how to use the press brake, stretch press, and other tools and equipment used in the sheet metal trade.[3]

[edit] Education

Fuller attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts, and after that began studying at Harvard University, where he was affiliated with Adams House. He was expelled from Harvard twice: first for spending all his money partying with a vaudeville troupe, and then, after having been readmitted, for his "irresponsibility and lack of interest." By his own appraisal, he was a non-conforming misfit in the fraternity environment.[3][edit] Wartime experience

Between his sessions at Harvard, Fuller worked in Canada as a mechanic in a textile mill, and later as a laborer in the meat-packing industry. He also served in the U.S. Navy in World War I, as a shipboard radio operator, as an editor of a publication, and as a crash rescue boat commander. After discharge, he worked again in the meat packing industry, thereby acquiring management experience. In 1917, he married Anne Hewlett. During the early 1920s, he and his father-in-law developed the Stockade Building System for producing light-weight, weatherproof, and fireproof housing—although the company would ultimately fail.[3][edit] Bankruptcy and depression

By age 32, Fuller was bankrupt[dubious ] and jobless, living in low-income public housing in Chicago, Illinois. In 1922,[4] Fuller's young daughter Alexandra died from complications from polio and spinal meningitis. Allegedly, he felt responsible and this caused him to drink frequently and to contemplate suicide for a while. He finally chose to embark on "an experiment, to find what a single individual [could] contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity."[5][edit] Recovery

In 1927 Fuller resolved to think independently which included a commitment to "the search for the principles governing the universe and help advance the evolution of humanity in accordance with them... finding ways of doing more with less to the end that all people everywhere can have more and more."[citation needed] By 1928, Fuller was living in Greenwich Village and spending much of his time at the popular café Romany Marie's,[6] where he had spent an evening in conversation with Marie and Eugene O'Neill several years earlier.[7] Fuller accepted a job decorating the interior of the café in exchange for meals,[6] giving informal lectures several times a week,[7][8] and models of the Dymaxion house were exhibited at the café. Isamu Noguchi arrived during 1929—Constantin Brâncuşi, an old friend of Marie's,[9] had directed him there[6]—and Noguchi and Fuller were soon collaborating on several projects,[8][10] including the modeling of the Dymaxion car based on recent work by Aurel Persu.[11] It was the beginning of their lifelong friendship.[edit] Geodesic domes

Fuller taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina during the summers of 1948 and 1949,[12] serving as its Summer Institute director in 1949. There, with the support of a group of professors and students, he began reinventing a project that would make him famous: the geodesic dome. Although the geodesic dome had been created some 30 years earlier by Dr. Walther Bauersfeld, Fuller was awarded United States patents. He is credited for popularizing this type of structure.One of his early models was first constructed in 1945 at Bennington College in Vermont, where he frequently lectured. In 1949, he erected his first geodesic dome building that could sustain its own weight with no practical limits. It was 4.3 meters (14 ft) in diameter and constructed of aluminum aircraft tubing and a vinyl-plastic skin, in the form of an icosahedron. To prove his design, and to awe non-believers, Fuller suspended from the structure's framework several students who had helped him build it. The U.S. government recognized the importance of his work, and employed his firm Geodesics, Inc. in Raleigh, North Carolina to make small domes for the Marines. Within a few years there were thousands of these domes around the world.

His first "continuous tension – discontinuous compression" geodesic dome (full sphere in this case) was constructed at the University of Oregon Architecture School in 1959 with the help of students.[13] These continuous tension – discontinuous compression structures featured single force compression members (no flexure or bending moments) that did not touch each other and were 'suspended' by the tensional members.

[edit] Best-known work

For the next half-century, Fuller developed many ideas, designs and inventions, particularly regarding practical, inexpensive shelter and transportation. He documented his life, philosophy and ideas scrupulously by a daily diary (later called the Dymaxion Chronofile), and by twenty-eight publications. Fuller financed some of his experiments with inherited funds, sometimes augmented by funds invested by his collaborators, one example being the Dymaxion car project.[edit] World stage

The Montreal Biosphère by Buckminster Fuller, 1967

Fuller believed human societies would soon rely mainly on renewable sources of energy, such as solar- and wind-derived electricity. He hoped for an age of "omni-successful education and sustenance of all humanity." Fuller referred to himself as "the property of universe" and during one radio interview he gave later in life, declared himself and his work "the property of all humanity". For his lifetime of work, the American Humanist Association named him the 1969 Humanist of the Year.

In 1976, Fuller was a key participant at UN Habitat I, the first UN forum on human settlements.

[edit] Honors

Fuller was awarded 28 United States patents[15] and many honorary doctorates. In 1960, he was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal from The Franklin Institute. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968.[16] In 1970 he received the Gold Medal award from the American Institute of Architects. He also received numerous other awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom presented to him on February 23, 1983 by President Ronald Reagan.[edit] Last filmed appearance

Fuller's last filmed interview took place on April 3, 1983, in which he presented his analysis of Simon Rodia's Watts Towers as a unique embodiment of the structural principles found in nature. Portions of this interview appear in I Build the Tower, a documentary film on Rodia's architectural masterpiece.[edit] Death

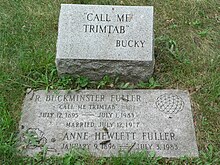

Gravestone (see trim tab)

[edit] Philosophy and worldview

The grandson of Unitarian minister Arthur Buckminster Fuller,[17] R. Buckminster Fuller was also Unitarian.[18] Buckminster Fuller was an early environmental activist. He was very aware of the finite resources the planet has to offer, and promoted a principle that he termed "ephemeralization", which, in essence—according to futurist and Fuller disciple Stewart Brand—Fuller coined to mean "doing more with less".[19] Resources and waste material from cruder products could be recycled into making more valuable products, increasing the efficiency of the entire process. Fuller also introduced synergetics, an encompassing term which he used broadly as a metaphoric language for communicating experiences using geometric concepts and, more specifically, to reference the empirical study of systems in transformation, with an emphasis on total system behavior unpredicted by the behavior of any isolated components. Fuller coined this term long before the term synergy became popular.Fuller was a pioneer in thinking globally, and he explored principles of energy and material efficiency in the fields of architecture, engineering and design.[20][21] He cited François de Chardenedes' opinion that petroleum, from the standpoint of its replacement cost out of our current energy "budget" (essentially, the net incoming solar flux), had cost nature "over a million dollars" per U.S. gallon (US$300,000 per litre) to produce. From this point of view, its use as a transportation fuel by people commuting to work represents a huge net loss compared to their earnings.[22] An encapsulation quotation of his views might be, "There is no energy crisis, only a crisis of ignorance."[23][24][25]

Fuller was concerned about sustainability and about human survival under the existing socio-economic system, yet remained optimistic about humanity's future. Defining wealth in terms of knowledge, as the "technological ability to protect, nurture, support, and accommodate all growth needs of life," his analysis of the condition of "Spaceship Earth" caused him to conclude that at a certain time during the 1970s, humanity had attained an unprecedented state. He was convinced that the accumulation of relevant knowledge, combined with the quantities of major recyclable resources that had already been extracted from the earth, had attained a critical level, such that competition for necessities was not necessary anymore. Cooperation had become the optimum survival strategy. "Selfishness," he declared, "is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable.... War is obsolete."[26] He criticized previous utopian schemes as too exclusive, and thought this was a major source of their failure. To work, he thought that a utopia needed to include everyone.[27]

So it is not surprising that he and others of his stature were attracted by Korzybski's ideas in general semantics. General semantics is a discipline of mind that seeks to unify persons and nations by changing their worldview reaction and the philosophy of their expression. In the 1950s Fuller attended seminars and workshops organized by the Institute of General Semantics, and he delivered the annual Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture in 1955.[28] Korzybski is mentioned in the Introduction of his book Synergetics. The two gentlemen shared a remarkable amount of similarity in their formulations of general semantics.[29]

In his 1970 book I Seem To Be a Verb, he wrote: "I live on Earth at present, and I don't know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing—a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process—an integral function of the universe."

Fuller claimed that the natural analytic geometry of the universe was based on arrays of tetrahedra. He developed this in several ways, from the close-packing of spheres and the number of compressive or tensile members required to stabilize an object in space. One confirming result was that the strongest possible homogeneous truss is cyclically tetrahedral.[30]

He had become a guru of the design, architecture, and 'alternative' communities, such as Drop City, the community of experimental artists to whom he awarded the 1966 "Dymaxion Award" for "poetically economic" domed living structures.

[edit] Major design projects

[edit] The geodesic dome

Fuller was most famous for his lattice shell structures – geodesic domes, which have been used as parts of military radar stations, civic buildings, environmental protest camps and exhibition attractions. An examination of the geodesic design by Walther Bauersfeld for the Zeiss-Planetarium, built some 20 years prior to Fuller's work, reveals that Fuller's Geodesic Dome patent (U.S. 2,682,235; awarded in 1954), follows the same design as Bauersfeld's.[31]Their construction is based on extending some basic principles to build simple "tensegrity" structures (tetrahedron, octahedron, and the closest packing of spheres), making them lightweight and stable. The geodesic dome was a result of Fuller's exploration of nature's constructing principles to find design solutions. The Fuller Dome is referenced in the Hugo Award-winning novel Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner, in which a geodesic dome is said to cover the entire island of Manhattan, and it floats on air due to the hot-air balloon effect of the large air-mass under the dome (and perhaps its construction of lightweight materials).[32]

[edit] Transportation

In the 1930s, Fuller designed and built prototypes of what he hoped would be a safer, aerodynamic car, which he called the Dymaxion. ("Dymaxion" is said to be a syllabic abbreviation of dynamic maximum tension, or possibly of dynamic maximum ion.)[33] Fuller worked with professional colleagues for three years beginning in 1932 on a design idea Fuller had derived from aircraft technologies. The three prototype cars were different from anything being sold at the time. They had three wheels: two front drive wheels and one rear, steered wheel. The engine was in the rear, and the chassis and body were original designs. The aerodynamic, somewhat tear-shaped body was large enough to seat eleven people and was about 18 feet (5.5 m) long, resembling a blend of a light aircraft (without wings) and a Volkswagen van of 1950s vintage. All three prototypes were essentially a mini-bus, and its concept long predated the Volkswagen Type 2 mini-bus conceived in 1947 by Ben Pon.Despite its length, and due to its three-wheel design, the Dymaxion turned on a small radius and could easily be parked in a tight space. The prototypes were efficient in fuel consumption for their day, traveling about 30 miles per gallon.[34] Fuller contributed a great deal of his own money to the project, in addition to funds from one of his professional collaborators. An industrial investor was also very interested in the concept. Fuller anticipated that the cars could travel on an open highway safely at up to about 160 km/h (100 miles per hour), but, in practice, they were difficult to control and steer above 80 km/h (50 mph). Investors backed out and research ended after one of the prototypes was involved in a high-profile collision that resulted in a fatality. In 2007, Time Magazine reported on the Dymaxion as one of the "50 worst cars of all time".[35]

In 1943, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser asked Fuller to develop a prototype for a smaller car, but Fuller's five-seater design was never developed further.

[edit] Housing

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (December 2010) |

A Dymaxion House at The Henry Ford.

Conceived nearly two decades before, and developed in Wichita, Kansas, the house was designed to be lightweight and adapted to windy climates. It was to be inexpensive to produce and purchase, and assembled easily. It was to be produced using factories, workers, and technologies that had produced World War II aircraft. It was ultramodern-looking at the time, built of metal, and sheathed in polished aluminum. The basic model enclosed 90 m² (1000 square feet) of floor area. Due to publicity, there were many orders during the early Post-War years, but the company that Fuller and others had formed to produce the houses failed due to management problems.

In 1969, Fuller began the Otisco Project, named after its location in Otisco, New York. The project developed and demonstrated concrete spray technology used in conjunction with mesh covered wireforms as a viable means of producing large scale, load bearing spanning structures built on site without the use of pouring molds, other adjacent surfaces or hoisting.

The initial construction method used a circular concrete footing in which anchor posts were set. Tubes cut to length and with ends flattened were then bolted together to form a duodeca-rhombicahedron (22 sided hemisphere) geodesic structure with spans ranging to 60 feet (18 m). The form was then draped with layers of ¼-inch wire mesh attached by twist ties. Concrete was then sprayed onto the structure, building up a solid layer which, when cured, would support additional concrete to be added by a variety of traditional means. Fuller referred to these buildings as monolithic ferroconcrete geodesic domes. The tubular frame form proved too problematic when it came to setting windows and doors, and was abandoned. The second method used iron rebar set vertically in the concrete footing and then bent inward and welded in place to create the dome's wireform structure and performed satisfactorily. Domes up to three stories tall built with this method proved to be remarkably strong. Other shapes such as cones, pyramids and arches proved equally adaptable.

The project was enabled by a grant underwritten by Syracuse University and sponsored by US Steel (rebar), the Johnson Wire Corp, (mesh) and Portland Cement Company (concrete). The ability to build large complex load bearing concrete spanning structures in free space would open many possibilities in architecture, and is considered as one of Fuller's greatest contributions.

[edit] Alternative map projection

Fuller also designed an alternative projection map, called the Dymaxion map. This was designed to show Earth's continents with minimum distortion when projected or printed on a flat surface.[edit] Quirks

Fuller was a frequent flier, often crossing time zones. He famously wore three watches; one for the current zone, one for the zone he had departed, and one for the zone he was going to.[36][37] Fuller also noted that a single sheet of newsprint, inserted over a shirt and under a suit jacket, provided completely effective heat insulation during long flights.[citation needed]He experimented with polyphasic sleep, which he called Dymaxion sleep. In 1943, he told Time Magazine that he had slept only two hours a day for two years. He quit the schedule because it conflicted with his business associates' sleep habits, but stated that Dymaxion sleep could help the United States win World War II.[38]

Fuller documented his life copiously from 1915 to 1983, approximately 270 feet (82 m) of papers in a collection called the Dymaxion Chronofile. He also kept copies of all incoming and outgoing correspondence. The enormous Fuller Collection is currently housed at Stanford University.

If somebody kept a very accurate record of a human being, going through the era from the Gay 90s, from a very different kind of world through the turn of the century—as far into the twentieth century as you might live. I decided to make myself a good case history of such a human being and it meant that I could not be judge of what was valid to put in or not. I must put everything in, so I started a very rigorous record.[39][40]In his youth, Fuller experimented with several ways of presenting himself: R. B. Fuller, Buckminster Fuller, but as an adult finally settled on R. Buckminster Fuller, and signed his letters as such. However, he preferred to be addressed as simply "Bucky".

[edit] Practical achievements

Fuller introduced a number of concepts, and helped develop others. Certainly, a number of his projects were not successful in terms of commitment from industry or acceptance by most of the public. However, more than 500,000 geodesic domes have been built around the world and many are in use. According to the Buckminster Fuller Institute,[41] the largest geodesic-dome structures are:- Seagaia Ocean Dome: Miyazaki, Japan, 216 m (710 ft).

- Multi-Purpose Arena: Nagoya, Japan, 187 m (614 ft).

- Tacoma Dome: Tacoma, Washington, USA, 162 m (530 ft).

- Superior Dome: Northern Michigan Univ. Marquette, Michigan, USA, 160 m (525 ft).

- Walkup Skydome: Northern Arizona Univ. Flagstaff, Arizona, USA, 153 m (502 ft).

- Poliedro de Caracas: Caracas, Venezuela, 145 m (475 ft).[42][43][44]

- Round Valley High School Stadium: Springerville-Eagar, Arizona, USA, 134 m (440 ft).

- Former Spruce Goose Hangar: Long Beach, California, USA, 126 m (415 ft).

- Formosa Plastics Storage Facility: Mai Liao, Taiwan, 123 m (402 ft).

- Union Tank Car Maintenance Facility: Baton Rouge, Louisiana USA, 117 m (384 ft), destroyed in November 2007.[45]

- Lehigh Portland Cement Storage Facility: Union Bridge, Maryland USA, 114 m (374 ft).

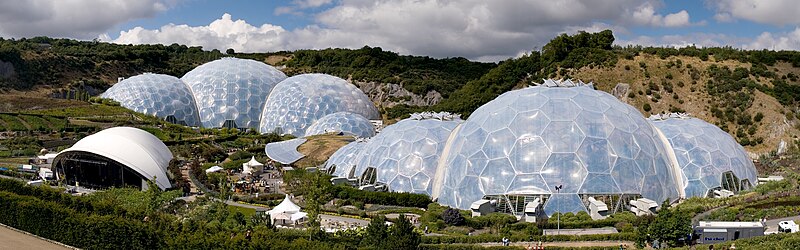

- The Eden Project, Cornwall, United Kingdom[46]

Panoramic view of the geodesic domes at the Eden Project

- Spaceship Earth at Disney World's Epcot Center in Florida, 80.8-meters (265 ft) wide (Spaceship Earth is actually a self-supporting geodesic sphere, the only one currently in existence.)

- The Gold Dome in Oklahoma City, formerly a bank and now a multicultural society and business center.

- Downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, is a geodesic sphere hosting the Telus World of Science, a science centre (formerly called Science World), that was originally the Expo Centre built for Expo 86.

- The dome over a shopping center in downtown Ankara, Turkey, 109.7-meter (360 ft) tall

- The dome enclosing a civic center in Stockholm, Sweden, 85.3-meter (280 ft) high.

- The world's largest aluminum dome formerly housed the “Spruce Goose” airplane in Long Beach Harbor, California, USA.

A spin-off of Fuller's dome-design conceptualization was the Buckminster Ball, which was the official FIFA approved design for footballs (association football), from their introduction at the 1970 World Cup until recently. The design was a truncated icosahedron – essentially a "Geodesic Sphere", consisting of 12 pentagonal and 20 hexagonal panels. This was used continuously for 34 years until replaced by the 14-panel Teamgeist for the 2006 World Cup.

Fuller was followed (historically) by other designers and architects, such as Sir Norman Foster and Steve Baer, willing to explore the possibilities of new geometries in the design of buildings, not based on conventional rectangles.

[edit] Language and neologisms

Buckminster Fuller spoke and wrote in a unique style and said it was important to describe the world as accurately as possible.[47] Fuller often created long run-on sentences and used unusual compound words (omniwell-informed, intertransformative, omni-interaccommodative, omniself-regenerative) as well as terms he himself invented.[48]Fuller used the word Universe without the definite or indefinite articles (the or a) and always capitalized the word. Fuller wrote that "by Universe I mean: the aggregate of all humanity's consciously apprehended and communicated (to self or others) Experiences."[49]

The words "down" and "up", according to Fuller, are awkward in that they refer to a planar concept of direction inconsistent with human experience. The words "in" and "out" should be used instead, he argued, because they better describe an object's relation to a gravitational center, the Earth. "I suggest to audiences that they say, 'I'm going "outstairs" and "instairs."' At first that sounds strange to them; They all laugh about it. But if they try saying in and out for a few days in fun, they find themselves beginning to realize that they are indeed going inward and outward in respect to the center of Earth, which is our Spaceship Earth. And for the first time they begin to feel real 'reality.'"[50]

"World-around" is a term coined by Fuller to replace "worldwide". The general belief in a flat Earth died out in Classical antiquity, so using "wide" is an anachronism when referring to the surface of the Earth—a spheroidal surface has area and encloses a volume but has no width. Fuller held that unthinking use of obsolete scientific ideas detracts from and misleads intuition. Other neologisms collectively invented by the Fuller family, according to Allegra Fuller Snyder, are the terms "sunsight" and "sunclipse", replacing "sunrise" and "sunset" to overturn the geocentric bias of most pre-Copernican celestial mechanics.

Fuller also invented the word "livingry," as opposed to weaponry (or "killingry"), to mean that which is in support of all human, plant, and Earth life. "The architectural profession—civil, naval, aeronautical, and astronautical—has always been the place where the most competent thinking is conducted regarding livingry, as opposed to weaponry."[51]

As well as contributing significantly to the development of tensegrity technology, Fuller invented the term "tensegrity" from tensional integrity. "Tensegrity describes a structural-relationship principle in which structural shape is guaranteed by the finitely closed, comprehensively continuous, tensional behaviors of the system and not by the discontinuous and exclusively local compressional member behaviors. Tensegrity provides the ability to yield increasingly without ultimately breaking or coming asunder."[52]

"Dymaxion" is a portmanteau of "dynamic maximum tension". It was invented by an adman about 1929 at Marshall Field's department store in Chicago to describe Fuller's concept house, which was shown as part of a house of the future store display. These were three words that Fuller used repeatedly to describe his design.

Fuller also helped to popularise the concept of Spaceship Earth: "The most important fact about Spaceship Earth: an instruction manual didn't come with it."[53]

[edit] Concepts and buildings

His concepts and buildings include:

|

|

[edit] Influence and legacy

Among the many people who were influenced by Buckminster Fuller are: Constance Abernathy,[56] Ruth Asawa,[57] J. Baldwin,[58][59] Michael Ben-Eli,[60] Pierre Cabrol,[61] Joseph Clinton,[62] Peter Floyd,[60] Medard Gabel,[63] Michael Hays,[60] David Johnston,[64] Robert Kiyosaki,[65] Peter Pearce,[60] Shoji Sadao,[60] Edwin Schlossberg,[60] Kenneth Snelson,[57][66][67] Robert Anton Wilson[68] and Stewart Brand.[69]An allotrope of carbon, fullerene—and a particular molecule of that allotrope C60 (buckminsterfullerene or buckyball) has been named after him. The Buckminsterfullerene molecule, which consists of 60 carbon atoms, very closely resembles a spherical version of Fuller's geodesic dome. The 1996 Nobel prize in chemistry was given to Kroto, Curl, and Smalley for their discovery of the fullerene.[70]

On July 12, 2004, the United States Post Office released a new commemorative stamp honoring R. Buckminster Fuller on the 50th anniversary of his patent for the geodesic dome and by the occasion of his 109th birthday.

Fuller was the subject of two documentary films: The World of Buckminster Fuller (1971) and Buckminster Fuller: Thinking Out Loud (1996). Additionally, filmmaker Sam Green and the band Yo La Tengo collaborated on a 2012 "live documentary" about Fuller, The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller.[71]

In June 2008, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented "Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe", the most comprehensive retrospective to date of his work and ideas.[72] The exhibition traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 2009. It presented a combination of models, sketches, and other artifacts, representing six decades of the artist's integrated approach to housing, transportation, communication, and cartography. It also featured the extensive connections with Chicago from his years spent living, teaching, and working in the city.[73]

In 2009 Noel Murphy wrote and performed the one-man show Buckminster Fuller LIVE! and then later on in 2010 Murphy directed the documentary film, The Last Dymaxion: Buckminster Fuller's Dream Restored.[citation needed]

In 2012, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art hosted "The Utopian Impulse" - a show about Buckminster Fuller's influence in the Bay Area. Featured were concepts, inventions and designs for creating "free energy" from natural forces, and for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. The show ran January through July.[citation needed]

[edit] Patents

(from the Table of Contents of Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller (1983) ISBN 0-312-43477-4)- 1927 U.S. Patent 1,633,702 Stockade: Building Structure

- 1927 U.S. Patent 1,634,900 Stockade: Pneumatic Forming Process

- 1928 (Application Abandoned) 4D House

- 1937 U.S. Patent 2,101,057 Dymaxion Car

- 1940 U.S. Patent 2,220,482 Dymaxion Bathroom

- 1944 U.S. Patent 2,343,764 Dymaxion Deployment Unit (sheet)

- 1944 U.S. Patent 2,351,419 Dymaxion Deployment Unit (frame)

- 1946 U.S. Patent 2,393,676 Dymaxion Map

- 1946 (No Patent) Dymaxion House (Wichita)

- 1954 U.S. Patent 2,682,235 Geodesic Dome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,881,717 Paperboard Dome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,905,113 Plydome

- 1959 U.S. Patent 2,914,074 Catenary (Geodesic Tent)

- 1961 U.S. Patent 2,986,241 Octet Truss

- 1962 U.S. Patent 3,063,521 Tensegrity

- 1963 U.S. Patent 3,080,583 Submarisle (Undersea Island)

- 1964 U.S. Patent 3,139,957 Aspension (Suspension Building)

- 1965 U.S. Patent 3,197,927 Monohex (Geodesic Structures)

- 1965 U.S. Patent 3,203,144 Laminar Dome

- 1965 (Filed – No Patent) Octa Spinner

- 1967 U.S. Patent 3,354,591 Star Tensegrity (Octahedral Truss)

- 1970 U.S. Patent 3,524,422 Rowing Needles (Watercraft)

- 1974 U.S. Patent 3,810,336 Geodesic Hexa-Pent

- 1975 U.S. Patent 3,863,455 Floatable Breakwater

- 1975 U.S. Patent 3,866,366 Non-symmetrical Tensegrity

- 1979 U.S. Patent 4,136,994 Floating Breakwater

- 1980 U.S. Patent 4,207,715 Tensegrity Truss

- 1983 U.S. Patent 4,377,114 Hanging Storage Shelf Unit

[edit] Bibliography

- 4d Timelock (1928)

- Nine Chains to the Moon (1938)

- Untitled Epic Poem on the History of Industrialization (1962)

- Ideas and Integrities, a Spontaneous Autobiographical Disclosure (1963) ISBN 0-13-449140-8

- No More Secondhand God and Other Writings (1963)

- Education Automation: Freeing the Scholar to Return (1963)

- What I Have Learned: A Collection of 20 Autobiograhical Essays, Chapter "How Little I Know", (1968)

- Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968) ISBN 0-8093-2461-X

- Utopia or Oblivion (1969) ISBN 0-553-02883-9

- Approaching the Benign Environment (1970) ISBN 0-8173-6641-5 (with Eric A. Walker and James R. Killian, Jr.)

- I Seem to Be a Verb (1970) coauthors Jerome Agel, Quentin Fiore, ISBN 1-127-23153-7

- Intuition (1970)

- Buckminster Fuller to Children of Earth (1972) compiled and photographed by Cam Smith, ISBN 0-385-02979-9

- The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller (1960, 1973) coauthor Robert Marks, ISBN 0-385-01804-5

- Earth, Inc (1973) ISBN 0-385-01825-8

- Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking (1975) in collaboration with E.J. Applewhite with a preface and contribution by Arthur L. Loeb, ISBN 0-02-541870-X

- Tetrascroll: Goldilocks and the Three Bears, A Cosmic Fairy Tale (1975)

- And It Came to Pass — Not to Stay (1976) ISBN 0-02-541810-6

- R. Buckminster Fuller on Education (1979) ISBN 0-87023-276-2

- Synergetics 2: Further Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking (1979) in collaboration with E.J. Applewhite

- Buckminster Fuller Sketchbook (1981)

- Critical Path (1981) ISBN 0-312-17488-8

- Grunch of Giants (1983) ISBN 0-312-35193-3

- Inventions: The Patented Works of R. Buckminster Fuller (1983) ISBN 0-312-43477-4

- Humans in Universe (1983) coauthor Anwar Dil, ISBN 0-89925-001-7

- Cosmography: A Posthumous Scenario for the Future of Humanity (1992) coauthor Kiyoshi Kuromiya, ISBN 0-02-541850-5

[edit] See also

- The Buckminster Fuller Challenge

- Cloud nine (Tensegrity sphere)

- Design science revolution

- Emissions Reduction Currency System

- Noosphere

- Old Man River's City project

- Spome

- Whole Earth Catalog

[edit] References

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. (2007). "Fuller, R Buckminster". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9365050. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ Victor Serebriakoff (1986). Mensa: The Society for the Highly Intelligent. Stein and Day. pp. 299, 304. ISBN 0-8128-3091-1.

- ^ a b c Pawley, Martin (1991). Buckminster Fuller. New York: Taplinger. ISBN 0-8008-1116-X.

- ^ R. Buckminster Fuller, Your Private Sky, Page 27

- ^ Design – A Three-Wheel Dream That Died at Takeoff – Buckminster Fuller and the Dymaxion Car – NYTimes.com

- ^ a b c John Haber. "Before Buckyballs". Review of Noguchi Museum Best of Friends exhibit (May 19, 2006 – October 15, 2006). http://www.haberarts.com/fuller.htm. "Noguchi, then twenty-five, had already had enough influences for a lifetime — from birth in Los Angeles, to childhood in Japan and the Midwest, to premedical classes at Columbia, to academic sculpture on the Lower East Side, to Brancusi's circle in Paris. Now his exposure to Modernism and "the American century" received a decidedly New York influence.

"Only two years before, on the brink of suicide, Fuller had decided to remake his life and the world. Why not begin on Minetta Street? In 1929, he was shopping around his first major design, plans for an inexpensive, modular home that others air-lift right where desired. Now, in exchange for meals, he took on the interior decoration and chairs for Marie's new location. He must have stood out in person, too, ever the talkative, handsome visionary in tie and starched collar."

See also: "The Architect and the Sculptor: A Friendship of Ideas". Grace Glueck, The New York Times. May 19, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/19/arts/design/19nogu.html. Retrieved April 27, 2010." - ^ a b Lloyd Steven Sieden. Buckminster Fuller's Universe: His Life and Work (pp. 74, 119–142). New York: Perseus Books Group, 2000. ISBN 0-7382-0379-3. p. 74: "Although O'Neill soon became well known as a major American playwright, it was Romany Marie who would significantly influence Bucky, becoming his close friend and confidante during the most difficult years of his life."

- ^ a b John Haskell. "Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi". Kraine Gallery Bar Lit, Fall 2007. http://www.kgbbar.com/lit/features/buckminster_ful.html.

- ^ Robert Schulman. Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village (pp. 85–86, 109–110). Louisville: Butler Books, 2006. ISBN 1-884532-74-8.

- ^ "Interview with Isamu Noguchi". Conducted November 7, 1973 by Paul Cummings at Noguchi's studio in Long Island City, Queens. Smithsonian Archives of American Art. http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/tranSCRIPTs/noguch73.htm.

- ^ Michael John Gorman (updated March 12, 2002). "Passenger Files: Isamu Noguchi, 1904–1988". Towards a cultural history of Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion Car. Stanford Humanities Lab. http://hotgates.stanford.edu/Bucky/dymaxion/noguchi.htm. Includes several images.

- ^ "IDEAS + INVENTIONS: Buckminster Fuller and Black Mountain College". Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center Exhibit. July 15, 2005 – November 26, 2005. http://blackmountaincollege.org/content/view/45/60/.

- ^ The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller. ISBN 0-385-01804-5.

- ^ "The Center for Spirituality & Sustainability". Siue.edu. http://www.siue.edu/maps/tour/center-spirituality-sustainability.shtml. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Partial list of Fuller U.S. patents

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter F". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. http://www.amacad.org/publications/BookofMembers/ChapterF.pdf. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Arthur Buckminster Fuller

- ^ Buckminster Fuller: Designer of a New World

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1999). The Clock of the Long Now. New York: Basic. ISBN 0-465-04512-X.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1969). Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2461-X.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster; Applewhite, E. J. (1975). Synergetics. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-541870-X.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1981). Critical Path. New York: St. Martin's Press. xxxiv–xxxv. ISBN 0-312-17488-8.

- ^ Phil Ament. "Inventor R. Buckminster Fuller". Ideafinder.com. http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventors/fuller.htm. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "Buckminster Fuller World Game Synergy Anticapatory". YouTube. January 27, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYtQ_-rpAUo&feature=related. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ The Economist. http://www.economist.com/debate/days/view/159.

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (1981). "Introduction". Critical Path (First ed.). New York, N.Y.: St.Martin's Press. xxv. ISBN 0-312-17488-8. ""It no longer has to be you or me. Selfishness is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable as mandated by survival. War is obsolete."

- ^ Fuller, R. Buckminster (2008). Jaime Snyder. ed. Utopia or oblivion: the prospects for humanity. Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller Publishers. ISBN 978-3-03778-127-2.

- ^ "Notable Individuals Influenced by General Semantics". The Institute of General Semantics. http://www.generalsemantics.org/the-general-semantics-learning-center/overview-of-general-semantics/notable-individuals/.

- ^ Drake, Harold L.. "The General Semantics and Science Fiction of Robert heinlein and A. E. Van Vogt". General Semantics Bulletin 41. Institute of General Semantics. p. 144. http://www.generalsemantics.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/articles/gsb/gsb41-drake.pdf. "For his dissertation showing some relationships between formulations of Alfred Korzybski and Buckminster Fuller, plus documenting meetings and associations of the two gentlemen, he was given the 1973 Irving J . Lee Award in General Semantics offered by the International Society for General Semantics."

- ^ Edmondson, Amy, "A Fuller Explanation", Birkhauser, Boston, 1987, p19 tetrahedra, p110 octet truss

- ^ Geodesic Domes and Charts of the Heavens

- ^ The R. Buckminster Fuller FAQ: Geodesic Domes

- ^ "National Automobile Museum - collections". Archived from the original on 2008-02-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20080227075757/http://www.automuseum.org/NAM_collections_dymaxion2.shtml. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ "Stanford Magazine - 'I seem to be a verb...' - July/August 2012". http://alumni.stanford.edu/get/page/magazine/article/?article_id=54863. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- ^ "The 50 Worst Cars of All Time"

- ^ Annals of Innovation: Dymaxion Man: Reporting & Essays: The New Yorker

- ^ Fuller, Buckminster (1969). Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2461-X.

- ^ "Science: Dymaxion Sleep". Time. October 11, 1943. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,774680,00.html. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Buckminster Fuller conversations

- ^ "Stanford University Libraries & Academic Information Resources:". Sul.stanford.edu. June 22, 2005. http://www-sul.stanford.edu//depts/spc/fuller/about.html. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ "The Buckminster Fuller Institute | Buckminster Fuller Institute". Bfi.org. http://www.bfi.org/. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Poliedro de Caracas – Sightseeing with Google Satellite Maps

- ^ http://cityguides.salsaweb.com/belgium/reports/2001/20010120venezuelatravel/venezimages/caracas04.jpg

- ^ 2theadvocate.com News | Kansas City Southern razes geodesic dome — Baton Rouge, LA

- ^ – The Eden Project

- ^ "What is important in this connection is the way in which humans reflex spontaneously for that is the way in which they usually behave in critical moments, and it is often "common sense" to reflex in perversely ignorant ways that produce social disasters by denying knowledge and ignorantly yielding to common sense." Intuition, 1972 Doubleday, New York. p.103

- ^ He wrote a single unpunctuated sentence approximately 3000 words long titled "What I Am Trying to Do." And It Came to Pass – Not to Stay Macmillan Publishing, New York, 1976.

- ^ "How Little I Know" from And It Came to Pass – Not to Stay Macmillan, 1976

- ^ Intuition (1972).

- ^ Critical Path, page xxv.

- ^ Synergetics, page 372.

- ^ "Selected Quotes". http://www.cjfearnley.com/cgi-bin/cjf-fortunes.pl?srchstr=Fuller&name=Submit. 090810 cjfearnley.com

- ^ Salsbury, Patrick G. (2000) "Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science; An Introduction" Miqel.com

- ^ "Eight Strategies for Comprehensive Anticipatory Design Science" Buckminster Fuller Institute

- ^ thirteen.org website Helped organize Fuller's papers Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ a b Thomas T. K. Zung, Buckminster Fuller: Anthology for a New Millennium Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ Buckyworks Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ Buckworks Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f Makovsky, Paul; Lanks, Belinda and Pedersen, Martin C. (July 2008) "The Fuller Effect" Metropolis (Magazine, New York) 28(1): pp. 106–111

- ^ Noland, Carol (November 1, 2009) "Pierre Cabrol dies at 84; architect was lead designer of Hollywood's Cinerama Dome" Los Angeles Times, archived here [2] at WebCite

- ^ Buckminster Fuller Prize challenge Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ Thomas T. K. Zung, Buckminster Fuller: Anthology for a New Millennium Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ About David Johnston Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ Kiyosaki, Robert. Rich Dad's Conspiracy of the Rich: The 8 New Rules of Money, pp. 3–4. Business Plus, 2009. ISBN 978-0-446-55980-5

- ^ [3], Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition, Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ concerning Fuller and Snelson Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ Hi Times May 1981, Robert Anton Wilson interviews Buckminster Fuller Retrieved December 29, 2010

- ^ From Counterculture to Cyberculture: The Legacy of the Whole Earth Catalog (from minute 22:40) Retrieved August 16, 2012

- ^ Chemistry 1996

- ^ The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller Retrieved May 21, 2012

- ^ Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe

- ^ "Chicago's MCA to show Buckminster Fuller ~ Starting with the Universe". Art Knowledge News. 2009. http://www.artknowledgenews.com/R_Buckminster_Fuller_Starting_with_the_Universe.html. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

[edit] Further reading

- Applewhite, E. J. Cosmic Fishing: An account of writing Synergetics with Buckminster Fuller. 1977 (ISBN 0-02-502710-7)

- Applewhite, E. J., ed. Synergetics Dictionary, The Mind Of Buckminster Fuller; in four volumes. Garland Publishing, Inc. New York and London. 1986 (ISBN 0-8240-8729-1)

- Chu, Hsiao-Yun. "Fuller's Laboratory Notebook." Collections, Volume 4 Issue 4 Fall 2008 (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press), 295–306.

- Chu, Hsiao-Yun and Roberto Trujillo. New Views on R. Buckminster Fuller.(Stanford, CA; Stanford University Press, 2009) ISBN 0-8047-6279-1

- Eastham, Scott: American Dreamer. Bucky Fuller and the Sacred Geometry of Nature; The Lutterworth Press 2007, Cambridge; ISBN 978-0-7188-3031-1

- Edmondson, Amy: "A Fuller Explanation"; EmergentWorld LLC. 2007 (ISBN 978-0-6151-8314-5)

- Hatch, Alden Buckminster Fuller At Home In The Universe. 1974 (ISBN 0-440-04408-1) Crown Publishers, New York.

- Hoogenboom, Olive (1999). "Fuller, R. Buckminster". American National Biography. 8. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 559–562.

- Kenner, Hugh. Bucky: a guided tour of Buckminster Fuller. 1973 (ISBN 0-688-00141-6)

- Krausse, Joachim and Lichtenstein, Claude. ed. Your Private Sky, R. Buckminster Fuller: The Art Of Design Science. Lars Mueller Publishers. 1999 (ISBN 3-907044-88-6)

- McHale, John. R. Buckminster Fuller. George Brazillier, Inc., New York. hardback. 1962.

- Pawley, Martin. Buckminster Fuller. Taplinger Publishing Company, New York. 1991. hardcover (ISBN 0-8008-1116-X)

- Potter, R. Robert. Buckminster Fuller (Pioneers in Change Series). Silver Burdett Publishers. 1990 (ISBN 0-382-09972-9)

- Robertson, Donald. Mind's Eye Of Buckminster Fuller. 1974 (ISBN 0-533-01017-9) Vantage Press, Inc., New York.

- Snyder, Robert. Buckminster Fuller: An Autobiographical Monologue/Scenario. St. Martin's Press, New York. hardback. 1980 (ISBN 0-312-24547-5)

- Sterngold, James. "The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller." The New York Times [Arts Section], June 15, 2008.

- Ward, James, ed., The Artifacts Of R. Buckminster Fuller, A Comprehensive Collection of His Designs and Drawings in Four Volumes: Volume One. The Dymaxion Experiment, 1926–1943; Volume Two. Dymaxion Deployment, 1927–1946; Volume Three. The Geodesic Revolution, Part 1, 1947–1959; Volume Four. The Geodesic Revolution, Part 2, 1960–1983: Edited with descriptions by James Ward. Garland Publishing, New York. 1984 (ISBN 0-8240-5082-7 vol. 1, ISBN 0-8240-5083-5 vol. 2, ISBN 0-8240-5084-3 vol. 3, ISBN 0-8240-5085-1 vol. 4)

- Wong, Yunn Chii, The Geodesic Works of Richard Buckminster Fuller, 1948–1968 (The Universe as a Home of Man), PhD thesis, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Architecture, 1999.

- Wühr, Paul, Das falsche Buch. (Fuller appears as a character in this book.)

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Buckminster Fuller |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Buckminster Fuller |

- The Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

- Buckminster Fuller Institute

- Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom – February 23, 1983

- Works by Buckminster Fuller on Open Library at the Internet Archive

- Buckminster Fuller, a portrait by Ansel Adams

- Articles about Fuller

- WIRED article about Buckminster Fuller

- Dymaxion Man: The Visions of Buckminster Fuller by Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker (June 9, 2008)

- The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller New York Times article questioning Fuller's supposed consideration of suicide, (June 15, 2008)

- Collections

- Buckminster Fuller Digital Collection at Stanford includes 380 hrs. of streamed audio-visual material from Fuller's personal archive

- Buckminster Fuller Papers 1,200 feet (370 m) housed at Stanford University Libraries

- Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, York University – Archival photographs of Buckminster Fuller from the Toronto Telegram.

- Everything I Know

- "Everything I Know" Session, Philadelphia, 1975 at Stanford University Libraries archives

- The "Everything I Know" 42-hour lecture session — video, audio, and full transcripts.

- Media

- R. Buckminster Fuller on PBS

- Buckminster Fuller discussed on The State of Things

- The World of Buckminster Fuller at the Internet Movie Database, a 1974 documentary

- Buckminster Fuller: Thinking Out Loud at the Internet Movie Database, a 1996 episode of American Masters

- Critical Path: R. Buckminster Fuller at the Internet Movie Database, a 2004 short animated documentary

- Other resources

- CJ Fearnley's List of Buckminster Fuller Resources on the Internet

- Buckminster Fuller at Pionniers & Précurseurs. Includes a bibliography

| ||||||||||||||

|

Categories:

- 1895 births

- 1983 deaths

- American architects

- American architecture writers

- American industrial designers

- American inventors

- Geodesic domes

- American military personnel of World War I

- American non-fiction environmental writers

- American technology writers

- Bates College alumni

- Buckminster Fuller

- Harvard University alumni

- Futurologists

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Modernist architects

- The Hunger Project

- Milton Academy alumni

- People from Penobscot County, Maine

- Solar building designers

- High-tech architecture

- Modernist architecture

- Organic architecture

- Sustainability advocates

- Systems scientists

- Washington University in St. Louis faculty

- Alternative historians

- American Unitarians

- Whole Earth

- People from Milton, Massachusetts

- Southern Illinois University Carbondale faculty

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Black Mountain College faculty

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Mensans

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete