From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

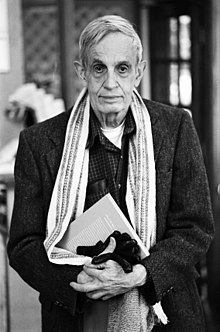

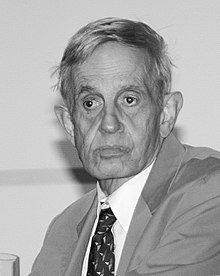

| John Forbes Nash, Jr. | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 13, 1928 Bluefield, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Residence | United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Mathematics, Economics |

| Institutions | Massachusetts Institute of Technology Princeton University |

| Alma mater | Princeton University, Carnegie Institute of Technology (now part of Carnegie Mellon University) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert W. Tucker |

| Known for | Nash equilibrium Nash embedding theorem Algebraic geometry Partial differential equations |

| Notable awards | John von Neumann Theory Prize (1978), Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (1994) |

| Spouse | Alicia Lopez-Harrison de Lardé (m. 1957–1963; 2001–present) |

Nash is the subject of the Hollywood movie A Beautiful Mind. The film, loosely based on the biography of the same name, focuses on Nash's mathematical genius and struggle with paranoid schizophrenia.[1][2]

In 2002, PBS produced a documentary about Nash titled A Brilliant Madness, which tells the story of a mathematical genius whose career was cut short by his descent into madness.

In his own words, he states,

- I later spent times of the order of five to eight months in hospitals in New Jersey, always on an involuntary basis and always attempting a legal argument for release. And it did happen that when I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research. In these interludes of, as it were, enforced rationality, I did succeed in doing some respectable mathematical research. Thus there came about the research for "Le problème de Cauchy pour les équations différentielles d'un fluide général"; the idea that Prof. Hironaka called "the Nash blowing-up transformation"; and those of "Arc Structure of Singularities" and "Analyticity of Solutions of Implicit Function Problems with Analytic Data".

- But after my return to the dream-like delusional hypotheses in the later 60's I became a person of delusionally influenced thinking but of relatively moderate behavior and thus tended to avoid hospitalization and the direct attention of psychiatrists.

- Thus further time passed. Then gradually I began to intellectually reject some of the delusionally influenced lines of thinking which had been characteristic of my orientation. This began, most recognizably, with the rejection of politically oriented thinking as essentially a hopeless waste of intellectual effort.[3]

Contents |

Early life and career

Nash was born on June 13, 1928, in Bluefield, West Virginia. His father, after whom he is named, was an electrical engineer for the Appalachian Electric Power Company. His mother, born Margaret Virginia Martin and known as Virginia, had been a schoolteacher before she married. Both parents pursued opportunities to supplement their son's education, providing him with encyclopedias and even allowing him to take advanced mathematics courses at a local college while still in high school. After attending Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) and graduating in 1948 with bachelor's and master's degrees in mathematics, he accepted a scholarship to Princeton University where he pursued his graduate studies in Mathematics.[3]Post-graduate career

Nash's advisor and former Carnegie Tech professor R.J. Duffin wrote a letter of recommendation consisting of a single sentence: "This man is a genius."[4] Nash was accepted by Harvard University, but the chairman of the mathematics department of Princeton, Solomon Lefschetz, offered him the John S. Kennedy fellowship, which was enough to convince Nash that Harvard valued him less.[5] Thus he went to Princeton where he worked on his equilibrium theory. He earned a doctorate in 1950 with a 28-page dissertation on non-cooperative games.[6] The thesis, which was written under the supervision of Albert W. Tucker, contained the definition and properties of what would later be called the "Nash equilibrium". These studies led to four articles:- Nash, JF (1950), "Equilibrium Points in N-person Games", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 36 (36): 48–9, doi:10.1073/pnas.36.1.48, PMC 1063129, PMID 16588946, MR0031701.

- "The Bargaining Problem", Econometrica (18): 155–62, 1950. MR0035977.

- Nash, J. (1951), "Non-cooperative Games", Annals of Mathematics 54 (54): 286–95[7], JSTOR 1969529.

- "Two-person Cooperative Games", Econometrica (21): 128–40, 1953, MR0053471.

- "Real algebraic manifolds", Annals of Mathematics (56): 405–21, 1952, MR0050928. See Proc. Internat. Congr. Math, AMS, 1952, pp. 516–17.

In the book A Beautiful Mind, author Sylvia Nasar explains that Nash was working on proving a theorem involving elliptic partial differential equations when, in 1956, he suffered a severe disappointment when he learned of an Italian mathematician, Ennio de Giorgi, who had published a proof just months before Nash achieved his proof. Each took different routes to get to their solutions. The two mathematicians met each other at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences of New York University during the summer of 1956. It has been speculated that if only one of them had solved the problem, he would have been given the Fields Medal for the proof.[3]

In 2011, the National Security Agency declassified letters written by Nash in 1950s, in which he had proposed a new encryption-decryption machine.[8] The letters show that Nash had anticipated many concepts of modern cryptography, which are based on computational hardness.[9]

Personal life

In 1951, Nash went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a C. L. E. Moore Instructor in the mathematics faculty. There, he met Alicia Lopez-Harrison de Lardé (born January 1, 1933), a physics student from El Salvador, whom he married in February 1957 at a Catholic ceremony, although Nash was an atheist.[10] She admitted Nash to a mental hospital in 1959 for schizophrenia; their son, John Charles Martin Nash, was born soon afterward, but remained nameless for a year because his mother felt that her husband should have a say in the name.Nash and de Lardé divorced in 1963, though after his final hospital discharge in 1970 Nash lived in de Lardé's house. They were remarried in 2001.

Nash has been a longtime resident of West Windsor Township, New Jersey.[11]

Mental illness

Schizophrenia

Nash began to show signs of extreme paranoia and his wife later described his behavior as erratic, as he began speaking of characters like Charles Herman and William Parcher who were putting him in danger. Nash seemed to believe that all men who wore red ties were part of a communist conspiracy against him. Nash mailed letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., declaring that they were establishing a government.[12][13]He was admitted to the McLean Hospital, April–May 1959, where he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. The clinical picture is dominated by relatively stable, often paranoid, fixed beliefs that are either false, over-imaginative or unrealistic, usually accompanied by experiences of seemingly real perception of something not actually present — particularly auditory and perceptional disturbances, a lack of motivation for life, and mild clinical depression.[14] Upon his release, Nash resigned from MIT, withdrew his pension, and went to Europe, unsuccessfully seeking political asylum in France and East Germany. He tried to renounce his U.S. citizenship. After a problematic stay in Paris and Geneva, he was arrested by the French police and deported back to the United States at the request of the U.S. government.

In 1961, Nash was committed to the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton. Over the next nine years, he spent periods in psychiatric hospitals, where, aside from receiving antipsychotic medications, he was administered insulin shock therapy.[14][15][16]

Although he sometimes took prescribed medication, Nash later wrote that he only ever did so under pressure. After 1970, he was never committed to the hospital again and he refused any medication. According to Nash, the film A Beautiful Mind inaccurately implied that he was taking the new atypical antipsychotics during this period. He attributed the depiction to the screenwriter (whose mother, he notes, was a psychiatrist), who was worried about encouraging people with the disorder to stop taking their medication.[17] Others, however, have questioned whether the fabrication obscured a key question as to whether recovery from problems like Nash's can actually be hindered by such drugs,[18] and Nash has said they are overrated and that the adverse effects are not given enough consideration once someone is deemed mentally ill.[19][20][21] According to Sylvia Nasar, author of the book A Beautiful Mind, on which the movie was based, Nash recovered gradually with the passage of time. Encouraged by his then former wife, de Lardé, Nash worked in a communitarian setting where his eccentricities were accepted. De Lardé said of Nash, "it's just a question of living a quiet life".[13]

Nash dates the start of what he terms "mental disturbances" to the early months of 1959 when his wife was pregnant. He has described a process of change "from scientific rationality of thinking into the delusional thinking characteristic of persons who are psychiatrically diagnosed as 'schizophrenic' or 'paranoid schizophrenic'"[22] including seeing himself as a messenger or having a special function in some way, and with supporters and opponents and hidden schemers, and a feeling of being persecuted, and looking for signs representing divine revelation.[23] Nash has suggested his delusional thinking was related to his unhappiness and his striving to feel important and be recognized, and to his characteristic way of thinking such that "I wouldn't have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally." He has said, "If I felt completely pressureless I don't think I would have gone in this pattern".[24] He does not see a categorical distinction between terms such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[25] Nash reports that he did not hear voices until around 1964, later engaging in a process of rejecting them.[26] He reports that he was always taken to hospitals against his will, and only temporarily renounced his "dream-like delusional hypotheses" after being in a hospital long enough to decide to superficially conform - to behave normally or to experience "enforced rationality". Only gradually on his own did he "intellectually reject" some of the "delusionally influenced" and "politically oriented" thinking as a waste of effort. However, by 1995, although he was "thinking rationally again in the style that is characteristic of scientists," he says he also felt more limited.[22][27]

Recognition and later career

At Princeton, campus legend Nash became "The Phantom of Fine Hall" (Princeton's mathematics center), a shadowy figure who would scribble arcane equations on blackboards in the middle of the night. The legend appears in a work of fiction based on Princeton life, The Mind-Body Problem, by Rebecca Goldstein.In 1978, Nash was awarded the John von Neumann Theory Prize for his discovery of non-cooperative equilibria, now called Nash equilibria. He won the Leroy P. Steele Prize in 1999.

In 1994, he received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (along with John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten) as a result of his game theory work as a Princeton graduate student. In the late 1980s, Nash had begun to use email to gradually link with working mathematicians who realized that he was the John Nash and that his new work had value. They formed part of the nucleus of a group that contacted the Bank of Sweden's Nobel award committee and were able to vouch for Nash's mental health ability to receive the award in recognition of his early work.[citation needed]

As of 2011 Nash's recent work involves ventures in advanced game theory, including partial agency, which show that, as in his early career, he prefers to select his own path and problems. Between 1945 and 1996, he published 23 scientific studies.

Nash has suggested hypotheses on mental illness. He has compared not thinking in an acceptable manner, or being "insane" and not fitting into a usual social function, to being "on strike" from an economic point of view. He has advanced evolutionary psychology views about the value of human diversity and the potential benefits of apparently nonstandard behaviors or roles.[28]

Nash has developed work on the role of money in society. Within the framing theorem that people can be so controlled and motivated by money that they may not be able to reason rationally about it, he has criticized interest groups that promote quasi-doctrines based on Keynesian economics that permit manipulative short-term inflation and debt tactics that ultimately undermine currencies. He has suggested a global "industrial consumption price index" system that would support the development of more "ideal money" that people could trust rather than more unstable "bad money". He notes that some of his thinking parallels economist and political philosopher Friedrich Hayek's thinking regarding money and a nontypical viewpoint of the function of the authorities.[29][30]

Nash received an honorary degree, Doctor of Science and Technology, from Carnegie Mellon University in 1999, an honorary degree in economics from the University of Naples Federico II on March 19, 2003,[31] an honorary doctorate in economics from the University of Antwerp in April 2007, and was keynote speaker at a conference on Game Theory. He has also been a prolific guest speaker at a number of world-class events, such as the Warwick Economics Summit in 2005 held at the University of Warwick.

See also

Awards And Nominations

Double Helix MedalReferences

- ^ "Oscar race scrutinizes movies based on true stories". USA Today. March 6, 2002. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ "List of Oscar Winners". USA Today. March 25, 2002. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c "John F. Nash, Jr. - Autobiography". Nobel Foundation. 1994. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ Kuhn W, Harold; Sylvia Nasar (eds.). "The Essential John Nash" (PDF). Princeton University Press. pp. Introduction, xi. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ Nasar, Sylvia (1998), A Beautiful Mind, Simon & Schuster, pp. 46–7.

- ^ Osborne, MJ (2004), An Introduction to Game Theory, Oxford, ENG: Oxford University Press, p. 23.

- ^ Non-Cooperative Games; Dissertetion for PhD, Princeton University http://www.policonomics.com/wp-content/uploads/Non-Cooperative-Games.pdf

- ^ "2012 Press Release - National Cryptologic Museum Opens New Exhibit on Dr. John Nash". National Security Agency. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ "John Nash's Letter to the NSA ; Turing's Invisible Hand". Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Sylvia Nasar (1999). A Beautiful Mind: A Biography of John Forbes Nash, Jr., Winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, 1994. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684853703. "Nash, by then an atheist, balked at a Catholic ceremony. He would have been happy to get married in city hall."

- ^ Staff. "John Forbes Nash May Lose N.J. Home", Associated Press, March 14, 2002. Retrieved February 22, 2011. "West Windsor, N.J.: John Forbes Nash, whose life is chronicled in the Oscar-nominated movie A Beautiful Mind, could lose his home if the township picks one of its proposals to replace a nearby bridge."

- ^ Nasar, A Beautiful Mind, p. 251.

- ^ a b Nasar, Sylvia (November 13, 1994). "The Lost Years of a Nobel Laureate". New York Times.

- ^ a b Nasar, A Beautiful Mind, p. 32.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (2002), Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2003, Andrews McMeel Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7407-2691-0, retrieved July 10, 2008

- ^ Beam, Alex (2001), Gracefully Insane: The Rise and Fall of America's Premier Mental Hospital, PublicAffairs, ISBN 978-1-58648-161-2, retrieved July 10, 2008

- ^ John Nash "Interview by Marika Greihsel". Nobel Foundation. September 1, 2004

- ^ Whitaker, R. (March 4, 2002) "Mind drugs may hinder recovery". USA Today.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: Medication". 2002.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: Paths to Recovery". 2002.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: How does Recovery Happen?" 2002.

- ^ a b John Nash (1995) "Autobiography" from Les Prix Nobel. The Nobel Prizes 1994, Editor Tore Frängsmyr, [Nobel Foundation], Stockholm, 1952,

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: Delusional Thinking". 2002.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: The Downward Spiral" 2002.

- ^ John Nash (April 10, 2005) "Glimpsing inside a beautiful mind". Interview by Shane Hegarty. Schizophrenia.com.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: Hearing voices". 2002.

- ^ John Nash "PBS Interview: My experience with mental illness". 2002.

- ^ Neubauer, David (June 1, 2007). "John Nash and a Beautiful Mind on Strike". Yahoo Health. Archived from the original on 2008-04-21.

- ^ John Nash (2002) "Ideal Money" Southern Economic Journal, 69(1), p.4-11.

- ^ Zuckerman, Julia (April 27, 2005) "Nobel winner Nash critiques economic theory". The Brown Daily Herald.

- ^ Capua, Patrizia (19.3.2003). "Napoli, laurea a Nash il 'genio dei numeri'" (in Italian). la Repubblica.it.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: John Forbes Nash, Jr. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: John Forbes Nash |

- Autobiography at the Nobel Prize website

- Nash's home page at Princeton

- IDEAS/RePEc

- Nash FAQ from Princeton's Mudd Library, including a copy of his dissertation (PDF)

- Video of Dr. Sylvia Nasar narrating the story of John Nash at MIT

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "John Forbes Nash, Jr.", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- John Forbes Nash, Jr. at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- "A Brilliant Madness" — a PBS American Experience documentary

- John Nash speaks out about alleged omissions in film — Guardian Unlimited

- "John Nash and 'A Beautiful Mind'" John Milnor responds to A Beautiful Mind (book), focusing on Nash's achievements.

- John H. Lienhard (1994). "John Forbes Nash, Jr.". The Engines of Our Ingenuity. Episode 983. NPR. KUHF-FM Houston.

- "John F. Nash by Lao Long"

- Penn State's The 2003-2004 John M. Chemerda Lectures in Science: Dr. John F. Nash, Jr.

- video: Ariel Rubinstein's Lecture: "John Nash, Beautiful Mind and Game Theory"

- Lecture by John F. Nash at the Nobel Laureate Meeting in Lindau, Germany, 2005

- "Nash Equilibrium" 2002 Slate article by Robert Wright, about Nash's work and world government

- Video, with book, of Nash's meeting with Ennio De Giorgi, Trento, Italy, 1996.

- NSA releases Nash Encryption Machine plans to National Cryptologic Museum for public viewing, 2012

| [hide]

Nobel Memorial Laureates in Economics (1976–2000)

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

http://topdocumentaryfilms.com/a-brilliant-madness-john-nash/ | |

nice blog post

ReplyDelete3d printed products

3d printing materials

3d printer filament