The Social Credit proposals explained in 10

lessons

Lesson 4: The

solution:

debt-free money issued by society

debt-free money issued by society

The cost of servicing the

public debt increases proportionally to the debt, since it is a percentage of

this same debt. To finance its debt, the Federal Government sells Treasury Bills

and other bonds, most of them being bought by chartered banks.

As regards the sale of

Treasury bonds, the Government is a stupid seller: it does not sell its bonds to

the banks; it gives these bonds away to them, since these bonds cost the banks

nothing: the banks do not lend the money; they create it. Not only do banks get

something for nothing, but they also get interest on it.

On September 30, 1941, a

revealing exchange took place between Mr. Wright Patman, Chairman of the U.S.

House of Representatives Banking and Currency Committee, and Mr. Marriner

Eccles, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (the central bank of the U.S.A.)

concerning a $2 billion monetary issue which the Bank created:

|

|

|

Wright Patman

|

Marriner S. Eccles

|

Mr. Patman: "How did you get

the money to buy those $2 billion of Government securities?"

Mr. Eccles: "We created

it."

Mr. Patman: "Out of

what?"

Mr. Eccles: "Out of the

right to issue money, credit."

Mr. Patman: "And there is

nothing behind it, except the Government’s credit?"

Mr. Eccles: "We have the

Government bonds."

Mr. Patman: "That’s right,

the Government’s credit."

This puts us on the right

track for a solution to the debt problem: if these bonds are based on the

Government’s credit, why would the Government have to go through the banks to

use its own credit?

It is not the banker who

gives value to money, but the credit of the Government, of society. The only

thing the banker does in this transaction is to make an entry in a ledger,

writing figures which allow the country to make use of its own production

capacity, its own wealth.

Money is nothing else but

that: a figure — a figure which is a claim on products. Money is only a symbol,

a creation of the law, according to Aristotle’s words. Money is not wealth, but

the symbol that gives rights to wealth. Without products, money is worthless.

So, why pay for figures? Why pay for something which costs nothing to

make?

And since this money is

based on the production capacity of society, this money also belongs to society.

Then, why should society pay the bankers for the use of its own money? Why pay

for the use of our own goods? Why doesn’t the Government issue its own money

directly, without going through the banks?

|

|

Graham Towers

|

Even the first Governor of

the Bank of Canada admitted that the Federal Government had the right to issue

its own money. Graham Towers, who was Governor of the Bank from 1935 to 1951,

was asked the following question, before the Canadian Committee on Banking and

Commerce, in the spring of 1939:

Question: "Will you tell me

why a government with the power to create money should give that power away to a

private monopoly and then borrow that which Parliament can create itself, back

at interest, to the point of national bankruptcy?"

Towers’ answer: "Now, if

Parliament wants to change the form of operating the banking system, that is

certainly within the power of Parliament."

|

|

Thomas

Edison

|

U.S. inventor Thomas Edison

said: "If our nation can issue a

dollar bond, it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good,

makes the bill good also. The difference between the bond and the bill is that

the bond lets the money brokers collect twice the amount of the bond and an

additional 20 percent, whereas the currency pays nobody but those who contribute

directly to Muscle Shoals in some useful way...

"It is absurd to say that

our country can issue $30 million in bonds and not $30 million in currency. Both

are promises to pay, but one fattens the usurers and the other helps the people.

If the currency issued by the Government was no good, then the bonds would be no

good either. It is a terrible situation when the Government, to increase the

national wealth, must go into debt and submit to ruinous interest charges at the

hands of men who control the fictitious value of gold."

Here are some questions the

Social Crediters are often asked:

Question: Does the

Government have the power to create money? Would this money be as good as that

of the banks?

Answer: The Government has

indeed the power to create, issue the money of our country, since it is itself,

the Federal Government, that has given this power to the chartered banks. For

the Government to refuse to itself a privilege it has granted to the banks, is

the height of imbecility! Moreover, it is actually the first duty of any

sovereign government to issue its own currency, but all the countries today have

unjustly given up this power to private corporations, the chartered banks. The

first nation that thus surrendered to private corporations its power to create

money was Great Britain, back in 1694. In both Canada and the U.S.A., this right

was surrendered in 1913.

No danger of

inflation

Question: Is there not any

danger that the Government might misuse this power and issue too much money,

which would result in runaway inflation? Is it not preferable for the Government

to leave this power to the bankers, in order to keep it away from the whims of

the politicians?

Answer: The money issued by

the Government would be no more inflationary than the money created by the

banks: it would be the same figures, based on the same production of the

country. The only difference is that the Government would not have to get into

debt, or to pay interest, in order to obtain these figures.

On the contrary, the first

cause of inflation is precisely the money created as a debt by the banks:

inflation means increasing prices. The obligation for the corporations and

governments that are borrowing to bring back to the banks more money than the

banks created, forces the corporations to increase the prices of their products,

and the governments to increase their taxes.

What is the means used by

the present Governor of the Bank of Canada to fight inflation? Precisely what

actually increases it, that is to say, to increase the interest rates! As many

Premiers put it, "It is like trying to extinguish a fire by pouring gasoline

over it."

It is obvious that if the

Canadian Government decided to create or print money anyhow, without any limits,

according to the whims of the men in office, without any relation with the

existing production, there would definitely be runaway inflation. This is not at

all what is proposed here by the Social Crediters.

Accurate

bookkeeping

What the Social Crediters

advocate, when they speak of money created by the Government, is that money must

be brought back to its proper function, which is to be a figure, a ticket, that

represents products, which in fact is nothing but simple bookkeeping. And since

money is nothing but a bookkeeping system, the only necessary thing to do would

be to establish accurate bookkeeping:

The Government would appoint

a commission of accountants, an independent organism called the "National Credit

Office" (in Canada, the Bank of Canada could well carry out this job if ordered

to do so by the Government). This National Credit Office would be charged with

setting up accurate accounting, where money would be nothing but the reflection,

the exact financial expression, of economic realities: production would be

expressed in assets, and consumption in liabilities. Since one cannot consume

more than what has been produced, the liabilities could never exceed the assets,

and deficits and debts would be impossible.

In practice, here is how it

would work: the new money would be issued by the National Credit Office as new

products are made, and would be withdrawn from circulation as these products are

consumed (purchased). (Louis Even’s booklet, A Sound

and Effective Financial System, explains this mechanism in detail.) Thus

there would be no danger of having more money than products: there would be a

constant balance between money and products, money would always keep the same

value, and any inflation would be impossible. Money would not be issued

according to the whims of the Government nor of the accountants, since the

commission of accountants, appointed by the Government, would act only according

to the facts, according to what the Canadians produce and consume.

The best way to prevent any

price increase is to lower prices. And Social Credit does also propose a

mechanism to lower retail prices, called the "compensated discount", which would

allow the consumers to purchase all of the available production for sale with

the purchasing power they have at their disposal, by lowering retail prices (a

discount) by a certain percentage, so that the total retail prices of all the

goods for sale would equal the available total purchasing power of the consumer.

This discount would then be refunded to the retailers by the National Credit

Office. (This will be explained in Lesson 6.)

No more financial

problems

If the Government issued its

own money for the needs of society, it would be automatically able to pay for

all that can be produced in the country, and would no longer be obliged to

borrow from foreign or domestic financial institutions. The only taxes people

would pay would be for the services they consume. One would no longer have to

pay three or four times the actual price of public developments because of the

interest charges.

So, when the Government

would discuss a new project, it would not ask: "Do we have the money?", but: "Do

we have the materials and the workers to realize it?". If it is so, new money

would be automatically issued to finance this new production. Then the Canadians

could really live in accordance with their real means, the physical means, the

possibilities of production. In other words, all that is physically possible

would be made financially possible. There would be no more financial problems.

The only limit would be that of the producing capacity of the nation. The

Government would be able to finance all the developments and social programs

demanded by the population that are physically feasible.

Under the present debt-money

system, if the debt were to be paid off to the bankers, there would be no money

left in circulation, creating a depression infinitely worse than any of the

past. Let us quote again the exchange between Messrs. Patman and Eccles before

the House Banking and Currency Committee, on September 30, 1941:

Mr. Patman: "You have made

the statement that people should get out of debt instead of spending their

money. You recall the statement, I presume?"

Mr. Eccles: "That was in

connection with installment credit."

Mr. Patman: "Do you believe

that people should pay their debts generally when they can?"

Mr. Eccles: "I think it

depends a good deal upon the individual; but of course, if there were no debt in

our money system..."

Mr. Patman: "That is the

point I wanted to ask you about."

Mr. Eccles: "There wouldn’t

be any money."

Mr. Patman: "Suppose

everybody paid their debts, would we have any money to do business

on?"

Mr. Eccles: "That is

correct."

Mr. Patman: "In other words,

our system is based entirely on debt."

How can we ever hope to get

out of debt when all the money to pay off the debt is created by creating a

debt? Balancing the budget is an absurd straitjacket. What must be balanced is

the capacity to pay, in accordance with the capacity to produce, and not in

accordance with the capacity to tax. Since it is the capacity to produce that is

the reality, it is the capacity to pay that must be modeled on the capacity to

produce, to make financially possible what is physically feasible.

Repayment of the

debt

Paying off one’s debt is

simple justice if this debt is just. But if it is not the case, paying this debt

would be an act of weakness. As regards the public debt, justice is making no

debts at all, while developing the country. First, let us stop building new

debts. For the existing debt, the only bonds to be acknowledged would be those

of the savers; they who do not have the power to create money. The debt would

thus be reduced year after year, as bonds come to maturity.

The Government would honour

in full only the debts which, at their origins, represented a real expense on

the part of the creditor: the bonds purchased by individuals, and not the bonds

purchased with the money created by the banker, which are fictitious debts,

created by the stroke of a pen. As regards Third-World countries’ debts, they

are essentially owed to banks, which created all the money loaned to these

countries. These same countries would therefore have no interest charges to pay

back, and their debts would be, virtually, written off. Banks would lose

nothing, since it is they that had created this money, which did not exist

before.

|

|

John Paul II

|

Now we see how right are

those who call for a reform of the financial system and the cancellation of

debts, starting with Pope John Paul II, who wrote in his Apostolic Letter

Tertio Millennio Adveniente, for the celebration of the Jubilee of the

Year 2000:

"Thus, in the spirit of the

Book of Leviticus (25:8-12), Christians will have to raise their voice on behalf

of all the poor of the world, proposing the Jubilee as an appropriate time to

give thought, among other things, to reducing substantially, if not cancelling

outright, the international debt which seriously threatens the future of many

nations."

The social control of

money

|

|

St. Louis

IX

|

It is Saint Louis IX, King

of France, who said: "The first

duty of a king is to coin money when it is necessary for the sound economic life

of his subjects."

It is not at all necessary,

nor to be recommended, that banks be abolished or nationalized. The banker is an

expert in accounting and investing; he may well continue to receive and invest

savings with profit, taking his share of profits. But the creation of money is

an act of sovereignty which should not be left in the hands of a bank.

Sovereignty must be taken out of the hands of the banks and returned to the

nation.

Book money is a good modern

invention that should be retained. But instead of it proceeding from a private

pen, in the form of a debt, those figures, which serve as money, should come

from the pen of a national organism, in the form of money destined to serve the

people.

Therefore nothing is to be

turned upside down in the field of ownership or investment. There is no need to

abolish the current money and replace it with other kinds of money. All that is

needed is that a social monetary organism add enough of the same kind of money

to the money that already exists, according to the country’s possibilities and

the population’s needs.

We must stop suffering from

privations when there is everything needed in the country to bring comfort into

every home. The amount of money in circulation must be measured according to the

demand of the consumers for possible and useful goods.

It is therefore the

producers and consumers as a whole, the whole of society, which, in producing

goods to meet needs, should determine the amount of new money that an organism,

acting in the name of society, should put into circulation from time to time, in

accordance with the country’s developments.

Thus the people would

recover their right to live full lives, in accordance with the country’s

resources and the great possibilities of modern production.

Who owns the new

money?

Money should therefore be

put into circulation according to the rate of production and as the needs of

distribution dictate.

But to whom does this new

money belong when it comes into circulation in the country? — This money belongs

to the citizens themselves. It does not belong to the Government, which is not

the owner of the country, but only the protector of the common good; nor does it

belong to the accountants of the national monetary organism: like judges, they

carry out a social function and are paid, according to law, by society for their

services.

To which citizens? — To all.

This money is not a salary. It is new money injected into the public, so that

the people, as consumers, may obtain goods already made or easily realizable,

which are awaiting only sufficient purchasing power for them to be

produced.

One cannot imagine for one

moment that the new money, which comes gratuitously from a social organism, only

belongs to one or a few individuals in particular.

There is no other way, in

all fairness, of putting this new money into circulation than by distributing it

equally among all citizens without exception. Such a sharing also makes it

possible to derive the maximum benefit from the money, since it reaches into

every corner of the land.

Let us suppose that the

accountant who acts in the name of the nation finds it necessary to issue

another $1 million in order to meet the latest needs of the country. This

issuance could take the form of book money, the inscription of figures in

ledgers, as the banker does today.

Since there are 31 million

Canadians and 1 billion dollars to share, each citizen would get $32.25. So the

accountant would inscribe $32.25 in each citizen’s account. Such individual

accounts could easily be looked after by the local post offices, or by branches,

or by a bank owned by the nation.

This is the national

dividend. Each citizen would have an extra $32.25 to his own credit, in an

account bringing money into existence. This money would have been created and

put into circulation by a national monetary organism, an institution especially

established for this end by a law of Parliament.

To each the

dividend

Whenever it might become

necessary to increase the amount of money in a country, each man, woman and

child, regardless of age, would thus get his or her share of the new stage of

progress that makes the new money necessary.

This is not payment for a

job done, but a dividend to each one for his share in a common capital. If there

is private property, there is also community property that all possess in the

same way.

Here is a man who has

nothing but the rags he is covered with. Not a meal in front of him, not a penny

in his pocket. I can say to him:

"My dear fellow, you think

you are poor, but you are a capitalist who possesses a great deal of things in

the same way I and the Prime Minister do. The province’s waterfalls, the crown

forests, are yours as well as mine, and they can easily bring you in an annual

income.

"The social organization,

which makes it possible for our community to produce a hundred times more and

better than if we lived in isolation, is yours as well as mine, and must be

worth something to you as it is to me.

"Science, which makes

industry able to multiply production almost without human labour, is a heritage

passed on to each generation, a heritage that is continuously growing; and you,

who are a member of this generation just as I am, should have a share in this

legacy, just as I do.

"If you are poor and naked,

my friend, it is because your share has been stolen from you and put under lock

and key. When you have no food, it is not because the rich eat all the grain in

the land; it is because your share is still lying in the grain elevators. You

have been deprived of the means of getting that grain.

"The Social Credit dividend

will ensure that you get your share, or at least a major portion of it. A better

administration, freed from the financiers’ influence and able to cope with these

exploiters of men, will see to it that you get the rest.

"It is also this dividend

that will recognize you as a member of the human species, in virtue of which you

are entitled to a share of this world’s goods, at least the necessary share to

exercise your right to live."

Should money claim interest?

We believe that there is not

one thing in the world which lends itself to so much abuse as money. This is not

because money in itself is a bad thing. On the contrary, money is probably one

of man’s most brilliant inventions, making trade flexible, favouring the sale of

goods as required by needs, and making life in society easier.

But, to place money on an

altar is idolatry. To make of money a living thing, which gives birth to other

money, is unnatural.

Money does not breed money,

as the Greek philosopher Aristotle said. Yet, how many contracts are entered

into — contracts between individuals, contracts between governments and

creditors, which stipulate that money must breed money, or else properties or

freedoms are forfeited?

Little by little, everybody

has sided behind the theory, and especially behind the practice, that money must

produce interest. And in spite of all the Christian teaching to the contrary,

the practice has made so much headway that, so as not to lose in the furious

competition around the fertility of money, everybody must behave today as if it

was natural for money to breed money. The Church has not abrogated her old laws,

but it has become impossible for her to insist on their application.

The methods used to finance

World War II, in which we were Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin’s acolytes to

defend Christianity, solemnly consecrated the rule that money, even money thrown

into the sea or into the burning flames of cities, must bear interest. We refer

here to the Victory Bonds, which financed destruction, which did not produce

anything, and which had to bear interest just the same.

Interest and

dividends

So that our readers do not

pass out thinking about their savings put into industry or loan institutions,

let us hastily make a few distinctions.

If money cannot increase by

itself, there are things that money buys which logically produce developments.

Thus

I set aside $5,000 to

purchase a farm, or animals, seeds, trees, machinery. With intelligent work, I

will make these things produce others.

The $5,000 was an

investment. By itself it has not produced anything; but thanks to this $5,000, I

have been able to get things that have produced.

Let us suppose that I did

not have this $5,000. But my neighbour had it, and he did not need it for a

couple of weeks. He loaned it to me. I think it would be proper for me to show

my gratitude by letting him have a small portion of the products which I get,

thanks to the productive capital which I have thus been able to

obtain.

It is my work which has made

his capital profitable. But this capital itself represents accumulated work. We

are then two, whose activities — gone by for him, present for me — cause some

production to appear. The fact that he waited to draw on the country’s

production with the money he received as a reward for his work allowed me to get

the means of production that I would not have had without it.

We are therefore able to

divide the fruits of this collaboration between us. There remains to determine,

by agreement and equity, the part of production that is owed to the

capital.

What my lender will get in

this case is, strictly speaking, a dividend. (We divided the fruits of

production.)

The dividend is perfectly

justifiable, when production is fruitful.

* * *

This is not exactly the idea

that is generally attached to the word "interest". Interest is a claim made by

money, in function of time only, and independently of the results of the

loan.

Here is $1,000. I invest it

in federal, provincial, or municipal bonds. If I purchase bonds that bear 4%

interest, I ought to get $40 in interest every year, just as truly as the earth

will make one revolution around the sun during this period of time. Even if the

capital is used up without any profit, I must get my $40. That is

interest.

We cannot see anything that

justifies this claim, save that it is customary. It does not rest upon any

principle.

There is therefore

justification for a dividend, because it is subordinated to production growth.

There is no justification for interest in itself, because it is dissociated from

realities; it is based on the erroneous idea of a natural and periodical

generation of money.

Indirect

investments

In practice, he who brings

his money to the bank indirectly puts it into a productive industry. The bankers

are professional lenders, and the depositor passes his money to them, because

they are capable of making it thrive better than he can, without having to look

after it himself.

The small interest that the

banker enters to the depositor’s credit from time to time, even at fixed rates,

is in fact a dividend, a share from the income that the banker, with the help of

the borrowers, has obtained from productive activities.

Anonymous

investments

In passing, let us say a

word on the morality of investments. Many people are not preoccupied in the

least with the usefulness or the noxiousness of activities that their money will

finance. As long as it yields profits, they say, it is good. And the more profit

it yields, the better the investment is. A pagan would not reason

differently.

If a house-owner does not

have the right to rent his house to serve as a brothel, even though it would be

very profitable, the owner of savings does not have any more right to put them

into enterprises which ruin souls, even if the enterprises fill

pockets.

Moreover, it would be much

preferable for the backer and the entrepreneur to be less dissociated. The

smaller industry of old was much more sound: The financier and the entrepreneur

were the same person. The corner storekeeper is still in the same situation. The

chain stores are not. The co-operative, the association of people, keeps the

relation between the use of money and its owner, and has the advantage of making

possible enterprises which exceed the resources of one sole

individual.

The growth of

money

Let us go back to the

beginning question: Should money claim interest? We are therefore inclined to

answer: Money can claim dividends when there are fruits. Otherwise,

no.

If contracts are drafted

differently, if the farmer must pay back interest, even though he did not

receive any crop that year; if the farmers of Western Canada must honour

liabilities at 7%, when the Financiers who lead the world cause prices to fall

to one-third of what they were, this does not change anything about the

principle. The only thing this proves is that reality has been exchanged for

trickery.

But if money can claim

dividends, when there is a production increase, this production increase must

automatically create an increase in money. Otherwise, the dividend, while being

perfectly justifiable, becomes impossible to provide without dealing a blow to

the public from which it was extracted.

I was saying a few lines

above: If, thanks to the $5,000 which allowed me to buy ploughing implements, I

have increased my production, the lender is entitled to a share of these good

results. This is very easy to do if I let him have a share of these increased

products. But if it is money that I must give to him, it is quite another story.

If there is no increase of money in the public, my increased production creates

a problem: more offered goods, but no increase of money in step with them. I may

be successful at displacing another seller, but he will be the

victim.

You can tell me that the

$5,000 must have contributed to increasing money in circulation. Yes, but I must

pump back the $5,000, plus what I call the dividend, what others call

interest.

Then the problem is not

settled. And in our economic system, it cannot be. For money to increase, it is

necessary that the bank — the only place where the increase is created — lends

some somewhere. But in lending it, the bank exacts a repayment that is also

increased. The problem snowballs.

The Social Credit system

would settle that problem, as well as settle many other problems.

The dividend is a

legitimate, normal, logical thing. But the present system does not allow anyone

to pay it without making it hurt somewhere.

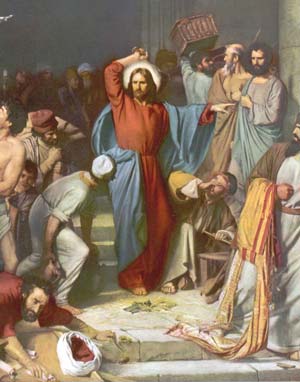

Our Lord drives the money

changers out of the Temple

As a matter of fact, the only passage in the

Gospel where it is mentioned that Jesus used force is when He drove the money

changers out of the Temple with a scourge of cords, and overthrew their tables

(as reported in Matthew 21:12-13 and Mark 11:15-19), precisely because they were

lending money at interest.

As a matter of fact, the only passage in the

Gospel where it is mentioned that Jesus used force is when He drove the money

changers out of the Temple with a scourge of cords, and overthrew their tables

(as reported in Matthew 21:12-13 and Mark 11:15-19), precisely because they were

lending money at interest.

There was, at that time, a

law that the tithes or taxes of the Temple could be paid only in one certain

coin called the "half shekel of the sanctuary", of which the money changers had

managed to obtain the monopoly. There were several different coins at that time,

but the people had to obtain this particular coin with which to pay their Temple

Tax. Moreover, the doves and the animals that the people bought for sacrifice

also could only be bought with this same special coin that the money changers

exchanged to the pilgrims, but at a cost of twice or more times its actual

worth, when it was used to buy commodities. So Jesus overthrew their tables, and

said:

"My house shall be called a

house of prayer; but you have made it a den of thieves."

The teaching of the

Church

The Bible contains several

texts that clearly condemn the lending of money at interest. Moreover, more than

300 years before Jesus Christ, the great Greek philosopher Aristotle also

condemned lending at interest, pointing out that "money, being naturally barren,

to make it breed money is preposterous." Furthermore, the Fathers of the Church,

since the remotest times, always unequivocally denounced usury. Saint Thomas

Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica (2, 2, Q. 78), thus summarized the teaching of

the Church on lending money at interest:

|

|

St. Thomas Aquinas

|

"It is written in the Book

of Exodus (22, 24): `If you lend money to any of my people who are poor, that

dwells with you, you shall not be hard upon them as an extortioner, nor oppress

them with usury.’ He who takes usury for a loan of money acts unjustly, for he

sells what does not exist, and such an action evidently constitutes an

inequality and, consequently, an injustice... It follows then that it is wrong

in itself to take a price (usury) for the use of money lent, and as in the case

of other offenses against justice, one is bound to make restitution of his

unjustly acquired money."

In reply to the text of the

Gospel on the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30 and Luke 19:12-27) which,

at first sight, seems to justify interest ("Wicked and slothful servant... why

did you not put my money into the bank, so that I might have recovered it with

interest when I came?"), Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote:

"The interest mentioned in

the Gospel must be taken in a figurative sense; it means the additional

spiritual goods asked of us by God, who wants us to always make better use of

the goods He entrusted us with, but this is for our benefit and not

His."

So this text of the Gospel

cannot justify interest since, as Saint Thomas says, "an argument cannot be

based on figurative expressions."

Another passage of the Bible

that presents difficulties is Deuteronomy 23:20-21: "You shall not demand

interest from your brother on a loan of money or food or of anything else. You

may demand interest from a foreigner, but not from your brother." Saint Thomas

explains:

"The Jews were forbidden to

take interest from `their brothers’, that is to say, from other Jews; this means

that demanding interest on a loan from anyone is wrong, strictly speaking, for

one must consider every man as `one’s neighbour and brother’, especially

according to the evangelical law that must rule mankind. So the Psalmist,

talking about the just man, says unreservedly: `he who lends not his money at

usury’ (14:4) and Ezekiel (18:17): `a son who accepts no interest or

usury’."

If the Jews were allowed to

demand interest from a foreigner, Saint Thomas wrote, it was tolerated in order

to avoid a greater evil, for fear that they might charge interest to other Jews,

the worshippers of the true God. Saint Ambrose, commenting on the same text,

gives to the word "foreigners" the meaning of "enemies", and concludes: "One may

seek interest from the one he legitimately wants to harm, from the one whom it

is lawful to wage war with."

Saint Ambrose also said:

"What is usury, if not killing a man?"

Saint John Chrysostom:

"Nothing is more shameful or cruel than usury."

Saint Leo: "The avarice that

claims to do its neighbour a good turn while it deceives him is unjust and

insolent... He who, among the other rules of a pious conduct, will not have lent

his money at usury, will enjoy eternal rest... whereas he who gets richer to the

detriment of others deserves, in return, eternal damnation."

In 1311, at the Council of

Vienna, Pope Clement V declared null and void all secular legislation in favour

of usury, and "all who fall into the error of obstinately, maintaining that the

exaction of usury is not sinful, shall be punished as

heretics."

Vix

pervenit

|

|

Benedict

XIV

|

On November 1, 1745, Pope

Benedict XIV issued the encyclical letter Vix Pervenit, addressed

to the Bishops of Italy, about contracts, and in which usury, or money-lending

at interest, is clearly condemned. On July 29, 1836, Pope Gregory XVI extended

this encyclical to the whole Church. It says:

"The kind of sin called

usury, which lies in the loan, consists in the fact that someone, using as an

excuse the loan itself — which by nature requires one to give back only as much

as one has received — demands to receive more than is due to him, and

consequently maintains that, besides the capital, a profit is due to him,

because of the loan itself. It is for this reason that any profit of this kind

that exceeds the capital is illicit and usurious.

"And in order not to bring

upon oneself this infamous note, it would be useless to say that this profit is

not excessive but moderate; that it is not large, but small... For the object of

the law of lending is necessarily the equality between what is lent and what is

given back... Consequently, if someone receives more than he lent, he is bound

in commutative justice to restitution..."

In 1891, Pope Leo XIII wrote

in his Encyclical Letter Rerum Novarum: "The mischief has been increased by rapacious usury, which,

although more than once condemned by the Church, is nevertheless, under a

different guise, but with like injustice, still practiced by covetous and

grasping men. "

On this matter, it is

interesting to consider the experience of the Islamic banks: the Koran — the

holy book of the Moslems — forbids usury, as the Bible of the Christians does.

But the Moslems took these words seriously and have set up, since 1979, a

banking system that conforms with the rules of the Koran: Islamic banks charge

no interest on neither current nor deposit accounts. They invest in business,

and pay a share of any profits to their depositors. This is not the Social

Credit system implemented in its entirety yet but, at least, it is a more than

worthy attempt at putting the banking system in keeping with moral

laws.

Very interesting but extremely difficult to read blue text on a red background.

ReplyDeleteSorry you found it difficult to read the text because of the blue text but that is how the template of this blog is set up for now. But at least you found it interesting. Personally, I have had no trouble reading the blue text.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, thank you for your response.