The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of fishing, commonly called the

South Sea Company,

[1] was a British

joint-stock company founded in 1711, created as a public-private partnership to consolidate and reduce the cost of national debt. The company was also granted a monopoly to trade with South America, hence its name. At the time it was created, Britain was involved in the

War of the Spanish Succession and Spain controlled South America. There was no realistic prospect that trade would take place and the company never realised any significant profit from its monopoly. Company stock rose greatly in value as it expanded its operations dealing in government debt, peaking in 1720 before collapsing to little above its original flotation price; this became known as the

South Sea Bubble.

A considerable number of persons were ruined by the share collapse, and the national economy greatly reduced as a result. The founders of the scheme engaged in

insider trading, using their advance knowledge of when national debt was to be consolidated to make large profits from purchasing debt in advance. Huge bribes were given to politicians to support the

Acts of Parliament necessary for the scheme. Company money was used to deal in its own shares, and selected individuals purchasing shares were given loans backed by those same shares to spend on purchasing more shares. The expectation of vast wealth from trade with South America was used to encourage the public to purchase shares, despite the limited likelihood this would ever happen. The only significant trade which did take place was in slaves, but the company failed to manage this profitably.

A parliamentary enquiry was held after the crash to discover its causes. A number of politicians were disgraced and persons found to have profited unlawfully from the company had assets confiscated proportionately to their gains (most had already been rich men and remained comfortably rich). The company was restructured and continued to operate for more than a century after the Bubble. The headquarters were in

Threadneedle Street at the centre of the financial district in London, in which street today can be found the

Bank of England. At the time of these events this also was a private company dealing in national debt, and the crash of its rival consolidated its position as banker to the British government.

[2]

The

Bubble Act, which forbade the creation of

joint-stock companies without

royal charter, was promoted by the South Sea company itself before its collapse. This was an effort to prevent the increasing competition for investors, which it saw from companies springing up around it.

[edit] Foundation

In August 1710

Robert Harley was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. The government at this time had become reliant upon the

Bank of England, a privately owned company which had obtained a monopoly to be the sole bank in England in return for arranging and managing loans to the government, but the government had become dissatisfied with the service it was receiving. Harley, therefore, was actively seeking new ways to improve the national finances. A new Parliament met in November 1710 with a resolve to attend to national finances which had suffered significantly from the costs of war with France. Harley came prepared, with detailed accounts as to the exact situation of national debt, which was customarily a piecemeal affair with different government departments arranging their own loans at need. He released the information steadily, continually adding new reports of debts incurred and scandalous expenditure until in January 1711 the House of Commons agreed to appoint a committee to investigate the entire debt. Members of the committee included Harley himself and the two

Auditors of the Imprests whose task was to investigate government spending,

Edward Harley brother of Robert and Paul Foley his brother in law. Also included were

William Lowndes Secretary of the Treasury who had had significant responsibility for re-minting the entire debased British coinage in 1696, and

John Aislabie who represented the

October Club, a group of around 200 MPs who had agreed to vote together.

[3]

Harley's first concern was to find £300,000 for the next quarter's pay for the British army operating in Europe under

Marlborough. This was provided by a private consortium of Edward Gibbon,

George Caswall and

Hoare's bank. The Bank of England had been operating a state lottery on behalf of the government which had not been particularly successful in 1710 and another had already begun in 1711. This too was performing poorly, so Harley granted authority for selling tickets to

John Blunt a director of the

Hollow Sword Blade Company, which despite its name was an unofficial bank. Commencing 3 March 1711 tickets had completely sold out by the 7th. This was the first truly successful English state lottery.

[4]

The success was shortly followed by another, larger, lottery 'The Two Million Adventure' or 'The Classis', with tickets costing £100, a maximum prize of £20,000 and every ticket winning a prize of at least £10. Although prizes were advertised by the total amount, they were paid in the form of a fixed sum annuity over a period of years, meaning the government effectively held the prize money as a loan until it was paid out to the winners. Marketing was handled by members of the Sword Blade syndicate, Gibbon distributing £200,000 of tickets and earning £4,500 commission, and Blunt distributing £993,000. Charles Blunt (a relative) was made Paymaster of the lottery with 'expenses' of £5,000.

[edit] Conception of the Company

The national debt investigation had concluded that a total of £9,000,000 was owed without any allocated income to pay it off. Edward Harley and John Blunt together had devised a scheme to consolidate this debt in a similar manner to that previously performed by the Bank of England, although the Bank still held the monopoly on operating as a bank. All holders of the identified debt would be required to surrender this to a new company, the South Sea Company, which in return would issue shares to the same amount. The government would pay the company £568,279 and 10s (6% interest plus expenses) annually, which would be distributed as a dividend to shareholders. The company was also given a monopoly to trade with South America, a potentially lucrative enterprise but one which was controlled by Spain, with whom Britain was at war.

[5]

At that time, when continental America was being explored and colonized, Europeans applied the term "South Seas" only to South America and surrounding waters, not to any other ocean. The concession both held out the potential for future profits and encouraged a desire for an end to the war, necessary if any profits were to be made. The original suggestion for the South Sea scheme has sometimes been credited to

Daniel Defoe, but it is more likely the idea originated with

William Paterson, one of the founders of the Bank of England and the

Darien Scheme, the disastrous failure of which contributed to Scotland agreeing to Unite with England.

[6]

Harley was rewarded for the scheme by being created Earl of Oxford on 23 May 1711 and was promoted to

Lord High Treasurer. With a more secure position, he began secret peace negotiations with France. Commercially, since the lotteries were discredited, some of the debt intended to be consolidated under the scheme was available in the open market before the scheme was announced, at a discounted rate of £55/£100 nominal value. This allowed anyone with advance knowledge to buy debt cheap and sell at an immediate profit, and made it possible for Harley to bring further financial supporters into the scheme, such as James Bateman and

Theodore Janssen.

[7]

Daniel Defoe commented:

"Unless the Spaniards are to be divested of common sense, infatuate, and given up, abandoning their own commerce, throwing away the only valuable stake they have left in the world, and in short, bent on their own ruin, we cannot suggest that they will ever, on any consideration, or for any equivalent, part with so valuable, indeed so inestimable a jewel, as the exclusive trade to their own plantations."

The originators of the scheme knew that there was no money to invest in a trading venture, and no realistic expectation there would ever be a trade to exploit, but the potential for great wealth was widely publicised at every opportunity, so as to encourage interest in the scheme. The objective for the founders was to create a company which they could use to become wealthy, and which offered future scope for further government deals.

[8]

[edit] Flotation

The "night singer of shares" sold stock on the streets during the

South Sea Bubble. Amsterdam, 1720.

The Charter for the company was drawn up by Blunt, based upon that of the Bank of England. Blunt was paid £3,846 for his services in setting up the company. Directors would be elected every three years while shareholders would meet twice a year. The company employed a Cashier, Secretary and Accountant. The Governor was intended to be an honorary position and was later customarily held by the ruling monarch. The charter allowed the full court of directors to nominate a smaller committee to act on any matter on its behalf. Anyone who was a director of the Bank of England or East India Company was disbarred from being a director of the South Sea company. Any ship owned by the company of more than 500 tons was to have a Church of England clergyman on board.

The exchange of government debt for stock was to occur in five separate lots. The first two of these, totaling £2.75 million from about 200 large investors, had already been arranged before the company's charter was issued on 10 September 1711. The government itself exchanged £0.75 million of its own debt held by different departments (at this time, individual office holders held responsibility for money in their charge, and were at liberty to invest it to their own advantage before it was required). Harley exchanged £8,000 of debt and was appointed Governor of the new company. Blunt, Caswall and Sawbridge together provided £65,000 Janssen £25,000 of his own plus £250,000 from a foreign consortium, Decker £49,000, Sir Ambrose Crawley £36,791. The company had a Sub-Governor, Bateman, Deputy Governor, Ongley and 30 ordinary directors. In total, nine of the directors were politicians, five were members of the Sword Blade consortium, and seven more were financial magnates who had been attracted to the scheme.

[9]

The company created a coat of arms with the motto 'A Gadibus usque ad Auroram' (from Cadiz to the dawn) and rented a large house in the City as its headquarters. Seven sub-committees were created to handle its everyday business, the most important being the 'Committee for the affairs of the company'. The Sword Blade company was retained as their banker and on the strength of its new government connections issued notes in its own right, notwithstanding the Bank of England monopoly. The task of the Company Secretary was to oversee trading activities, the Accountant, Grigsby, was responsible for registering and issuing stock, and the Cashier, Robert Knight, acted as Blunt's personal assistant at a salary of £200 per year.

[10]

[edit] Trading

The

War of the Spanish Succession did not end until March 1713, when the

Treaty of Utrecht granted Britain an

Asiento lasting 30 years to supply the Spanish colonies with 4,800 slaves per year. Britain was permitted to open offices in Buenos Aires, Caracas, Cartagena, Havana, Panama, Portobello and Vera Cruz to arrange the slave trade. One ship of no more than 500 tons could be sent to one of these places each year (the

Navío de Permiso) with general trade goods. One quarter of the profits were to be reserved for the King of Spain. There was provision for two extra sailings at the start of the contract. The Asiento was granted in the name of

Queen Anne and then contracted to the company.

[11]

By July the company had arranged contracts with the

Royal African Company to supply the necessary African slaves to Jamaica. £10 was paid for a slave aged over 16, £8 for one over 10. Two thirds were to be male, and 90% adult. The company trans-shipped 1,230 slaves from Jamaica to America in the first year, plus any which might have been added (against standing instructions) by the ship's captains on their own behalf. On arrival of the first cargoes, the local authorities refused to accept the Asiento, which had still not been officially confirmed there by the Spanish authorities. The slaves were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies.

[12]

In 1714 the government announced that a quarter of profits would be reserved for the queen and a further 7.5% for a financial advisor, Manasseh Gilligan. Some members of company board refused to accept the contract on these terms, and the government was obliged to reverse its decision.

[13]

Despite these setbacks, the company persisted, having raised £200,000 to finance the operations. In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, for 1716–1718, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. An import duty of 33

pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for purposes of payment slaves were not counted individually, but might only be counted as part slaves according to quality). One of the extra trade ships was sent to Cartagena in 1714 carrying woolen goods, despite warnings there was no market for them there, and they remained unsold for two years.

[14]

[edit] Changes of Management

The company was heavily dependent on the goodwill of government and so, when government changed, so too did the company board. In 1714 one of the directors who had been sponsored by Harley, Arthur Moore, had attempted to send 60 tons of private goods on board the company ship. He was dismissed as a director, but the result was the beginning of Harley's fall from favour with the company. On 27 July 1714, Harley was replaced as Lord High treasurer as a result of disagreement which had broken out within the Tory faction in parliament. Queen Anne died 1 August 1714 and at the election of directors in 1715 the Prince of Wales (future King

George II) was elected as Governor of the Company. The new King,

George I and the Prince of Wales both had significant holdings in the company as did some prominent Whig politicians, including James Cragg, the Earl of Halifax and Sir Joseph Jekyll. James Cragg, as Postmaster General, was responsible for intercepting mail on behalf of the government to obtain political and financial information. All Tory politicians were removed from the board and replaced with businessmen. Whigs, Horatio Townshend, brother in law of

Robert Walpole and the

Duke of Argyll were elected directors.

The new government led to a revival of the company's share value, which had fallen below its issue price. The previous government had failed to make the interest payments to the company for the last two years, owing more than £1 million. The new administration insisted the debt be written off, but allowed the company to issue new shares to stockholders to the value of the missed payments. At around £10 million, this now represented half the share capital issued in the entire country. In 1714 the company had 2-3,000 shareholders, more than either of its rivals.

[15]

By the time of the next director's elections in 1718 politics had changed again, with a schism within the Whigs between Walpole's faction supporting the Prince of Wales and

James Stanhope's supporting the King. Argyll and Townshend were dismissed as directors, as were surviving Tories Sir Richard Hoare and George Pitt, and King George I became Governor. Four members of parliament remained directors, as did six people holding government financial offices. The Sword Blade Company remained bankers to the South Sea, and indeed had flourished despite the company's doubtful legal position. Blunt remained a South Sea director, as did Sawbridge and they had been joined by Gibbon and Child. Caswall had retired as a South Sea director to concentrate on the Sword Blade business. In November 1718 Sub-Governor Bateman and Deputy Governor Shepheard both died. Leaving aside the honorary position of Governor, this left the company suddenly without its two most senior and experienced directors. They were replaced by Sir John Fellowes as Sub-Governor and Charles Joye as Deputy.

[16]

In 1718 war broke out with Spain once again. The company's assets in South America were seized, which the company claimed cost it £300,000. Any prospect of profit from trade, for which the company had purchased ships and had been planning its next ventures, disappeared.

[17]

[edit] Refinancing government debt

Events in France now came to influence the future of the South Sea company. A Scottish economist and financier,

John Law, exiled after killing a man in a duel, had travelled around Europe before settling in France. There he founded a bank, which in December 1718 became the Banque Royale, national bank of France, while Law himself was granted sweeping powers to control the economy of France, which operated largely by Royal decree. Law's remarkable success was known throughout Europe in financial circles and now came to inspire Blunt and his associates to make greater efforts to grow their own concerns.

[18]

In February 1719 Craggs explained to the House of Commons a new scheme for improving the national debt by converting the annuities issued after the 1710 lottery into South Sea stock. By Act of Parliament, the company was granted the right to issue £1,150 of new stock for every £100 of annuity which was surrendered. The government would pay 5% on the stock created, which would halve their annual bill. The conversion was voluntary, amounting to £2.5 million new stock if all converted. The company was to make an additional new loan to the government pro-rata up to £750,000, again at 5%.

[19]

The South Sea company chose to present the offer to the public in July 1719. In March there was an abortive attempt to restore the Old Pretender,

James Edward Stuart to the throne of Britain, with a small landing of troops in Scotland. They were defeated at the

Battle of Glen Shiel on 10 June. The Sword Blade company arranged to spread a rumour that the Pretender himself had been captured, and the general euphoria encouraged the South Sea share price to rise from £100 where it had been in the spring to £114. Annuitants were still paid out at the same money value of shares, the company keeping the profit from the rise in value before issuing. Approximately 2/3 of the available annuities were exchanged.

[edit] Trading more debt for equity

William Hogarth,

Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme (1721). In the bottom left corner are Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish figures gambling, while in the middle there is a huge machine, like a merry-go-round, which people are boarding. At the top is a goat, written below which is "Who'l Ride". The people are scattered around the picture with a sense of disorder, while the progress of the well dressed people towards the ride in the middle represent the foolishness of the crowd in buying stock in The South Sea Company, which spent more time issuing stock than anything else.

The 1719 scheme was a distinct success from the government's perspective and they sought to repeat it. Negotiations took place between Aislabie and Craggs for the government and Blunt, Cashier Knight and his assistant and Caswell. Janssen, the Sub Governor and Deputy Governor were also consulted but negotiations remained secret from most of the company. News from France was of fortunes being made investing in Law's bank whose shares had risen sharply. Money was moving around Europe, and other flotations threatened to soak up available capital (two insurance schemes in December 1719 each sought to raise £3 million).

[20]

Plans were made for a new scheme to take over most of the unconsolidated national debt of Britain (£30,981,712) in exchange for company shares. Annuities were valued as a lump sum necessary to produce the annual income over the original term at an assumed interest of 5%, which favoured those with shorter terms still to run. The government agreed to pay the same amount to the company for all the fixed term repayable debt as it had been paying before, but after seven years the 5% interest rate would fall to 4% on both the new annuity debt and also that taken over previously. After the first year, the company was to give the government £3 million in four quarterly installments. New stock would be created at a face value equal to the debt, but the share price was still rising and sales of the spare stock over and above that with a sale value equal to the debt would be used to raise the government fee plus a profit for the company. The more the price rose in advance of conversion, the more the company would make. Before the scheme, payments were costing the government £1.5 million per year.

[21]

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

- £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

- Privately held redeemable debt amounted to £16.5m

- £15m consisted of irredeemable annuities, long fixed-term annuities of 72–87 years and short annuities of 22 years remaining maturity

The purpose of this conversion was similar to the old one: Debt holders and annuitants might receive less return in total but a difficult-to-sell investment was transformed into shares which could be readily traded. Shares backed by national debt were considered a safe investment and a convenient method to hold and move money, far easier and safer than metal coins. The only alternative safe security, land, was much harder to sell and it was legally much more complex to transfer ownership.

The government received a cash payment and lower overall interest on the debt. Importantly, it also gained security over when the debt had to be repaid, which was not before seven years but then at its discretion. This avoided the risk that debt might become repayable at some future point just when the government needed to borrow more, and could be forced into paying higher interest rates. The payment to the government was to be used to buy in any debt not subscribed to the scheme, which although it helped the government also helped the company by removing possibly competing securities from the market, including large holdings by the Bank of England.

[22]

Company stock was now trading at £123, so the issue amounted to injecting £5 million of new money into a booming economy just as interest rates were falling.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for Britain at this point was estimated as £64.4 million.

[1]

[edit] Public announcement

On 21 January the plan was presented to the board of the South Sea company, and on 22 January

Chancellor of the Exchequer John Aislabie presented it to Parliament. The House was stunned into silence, but on recovering proposed the Bank of England should be invited to make a better offer. In response, the South Sea increased its cash payment to £3.5 million, while the Bank proposed to undertake the conversion with a payment of £5.5 million and a fixed conversion price of £170 for £100 face value Bank stock. On 1 February, the company negotiators led by Blunt raised their offer to £4 million plus a proportion of £3.5 million depending on how much of the debt was converted. They also agreed to the interest reduction happening after four years instead of seven, and to sell on behalf of the government £1 million of Exchequer bills (formerly handled by the Bank). The House accepted the South Sea offer. Bank stock fell sharply.

[23]

Perhaps the first sign of difficulty came as the South Sea announced that its Christmas 1719 dividend would be deferred for 12 months. The company now embarked on a show of gratitude to its friends. Select individuals were sold a parcel of company stock at the current price. The transactions were recorded by Knight in the names of intermediaries but no payments were received and no stock issued - indeed the company had none to issue until the conversion of debt began. The individual received an option to sell his stock back to the company at any future date at whatever market price might then apply. Shares went to the two Craggs, lords Gower and Lansdowne and four other members of Parliament. Sunderland would gain £500 for every pound that stock rose, George I's mistress, their children and Countess Platen £120 per pound rise, Aislabie £200 per pound, Stanhope £600 per pound. Others invested money, including the Treasurer to the Navy, Hampden, who invested £25,000 of government money on his own behalf.

[24]

The proposal was accepted in a slightly altered form in April 1720. Crucial in this conversion was the proportion of holders of irredeemable annuities that could be tempted to convert their securities at a high price for the new shares. (Holders of redeemable debt had effectively no other choice but to subscribe.) The South Sea Company could set the conversion price but could not diverge much from the market price of its shares. The company ultimately acquired 85% of the redeemables and 80% of the irredeemables.

[edit] Inflating the share price

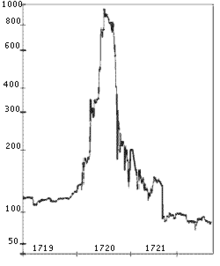

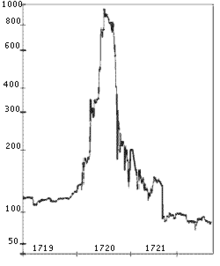

Chart of company stock prices.

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, to £550 at the end of May.

What may have supported the company's high multiples (its

P/E ratio) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held on to what shares they had been offered, with the option of selling them back to the company when and as they chose, receiving as "profit" the increase in market price. This method, while winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, etc., also had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the Company: in order to secure their own profits, they had to help drive up the stock. Meanwhile, by publicizing the names of their elite stockholders, the Company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

[edit] Bubble Act

The South Sea company was by no means the only company seeking to raise money from investors in 1720. A large number of other joint-stock companies had been created making extravagant claims (sometimes fraudulent) about foreign or other ventures or bizarre schemes. Others represented potentially sound, although novel, schemes, such as for founding insurance companies. These were nicknamed "Bubbles". Some of the companies had no legal basis, while others, such as the Hollow Sword Blade company acting as the South Sea's banker, used existing chartered companies for purposes entirely different to their creation. The York Buildings Company was set up to provide water to London, but was purchased by Case Billingsley who used it to purchase confiscated Jacobite estates in Scotland, which then formed the assets of an insurance company.

[25]

On 22 February 1720 John Hungerford raised the question of bubble companies in the House of Commons and persuaded the House to set up a committee, which he chaired, to investigate. He identified a number of companies which between them sought to raise £40 million in capital. The committee investigated the companies, establishing a principle that companies should not be operating outside the aims specified in their charters. A potential embarrassment for the South Sea was avoided when the question of the Hollow Sword Blade Company arose. Difficulty was avoided by flooding the committee with MPs who were supporters of the South Sea, and voting down the proposal to investigate the Hollow Sword by 75 to 25. (At this time, committees of the House were either 'Open' or 'secret'. A secret committee was one with a fixed set of members who could vote on its proceedings. By contrast, any MP could join in with an 'open' committee and vote on its proceedings.) Stanhope, who was a member of the committee, received £50,000 of the 'resaleable' South Sea stock from Sawbridge, a director of the Hollow Sword, at about this time. Hungerford had previously been expelled from the Commons for accepting a bribe.

[26]

Amongst the bubble companies investigated were two supported by Lords Onslow and Chetwynd respectively, for insuring shipping. These were criticised heavily, and the questionable dealings of the Attorney General and Solicitor General in trying to get charters for the companies led to both being replaced. However, the schemes had the support of Walpole and Craggs, so that the larger part of the Bubble act (which finally resulted in June 1720 from the committee's investigations) was devoted to creating charters for the

Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation and the

London Assurance Corporation. The companies were required to pay £300,000 for the privilege. The Act required that a joint stock company could only be incorporated by Act of Parliament or

Royal charter. The prohibition on unauthorised joint stock ventures was not repealed until 1825.

[27]

The passing of the Act added a boost to the South Sea Company, its shares leaping to £890 in early June. This peak encouraged people to start to sell; to counterbalance this the company's directors ordered their agents to buy, which succeeded in propping the price up at around £750.

[edit] Top reached

Tree caricature from Bubble Cards

The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about one hundred pounds a share to almost one thousand pounds per share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy as all types of people—from peasants to lords—developed a feverish interest in investing; in South Seas primarily, but in stocks generally. Among the many companies to go public in 1720 is — famously — one that advertised itself as "a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is".

[28]

The price finally reached £1,000 in early August and the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, dropping back to one hundred pounds per share before the year was out, triggering

bankruptcies amongst those who had bought on credit, and increasing selling, even

short selling — selling borrowed shares in the hope of buying them back at a profit if the price falls.

Also, in August 1720 the first of the installment payments of the first and second money subscriptions on new issues of South Sea stock were due. Earlier in the year John Blunt had come up with an idea to prop up the share price — the company would lend people money to buy its shares. As a result, many shareholders could not pay for their shares other than by selling them.

Furthermore, the scramble for liquidity appeared internationally as "bubbles" were also ending in Amsterdam and Paris. The collapse coincided with the fall of the

Mississippi Scheme of

John Law in France. As a result, the price of South Sea shares began to decline.

By the end of September the stock had fallen to £150. The company failures now extended to

banks and

goldsmiths as they could not collect loans made on the stock, and thousands of individuals were ruined, including many members of the

aristocracy. With investors outraged,

Parliament was recalled in December and an investigation began. Reporting in 1721, it revealed widespread

fraud amongst the company directors and corruption in the Cabinet. Among those implicated were

John Aislabie (the Chancellor of the Exchequer),

James Craggs the Elder (the

Postmaster General),

James Craggs the Younger (the

Southern Secretary), and even

Lord Stanhope and

Lord Sunderland (the heads of the Ministry). Craggs the Elder and Craggs the Younger both died in disgrace; the remainder were impeached for their corruption. Aislabie was imprisoned.

The newly appointed

First Lord of the Treasury Robert Walpole was forced to introduce a series of measures to restore public confidence. Under the guidance of Walpole, Parliament attempted to deal with the financial crisis. The estates of the directors of the company were confiscated and used to relieve the suffering of the victims, and the stock of the South Sea Company was divided between the Bank of England and East India Company. A resolution was proposed in parliament that bankers be tied up in sacks filled with snakes and tipped into the murky

Thames.

[29] The crisis had significantly damaged the credibility of

King George I and of the Whig Party.

[edit] Quotations prompted by the collapse

Joseph Spence wrote that Lord Radnor reported to him "When Sir

Isaac Newton was asked about the continuance of the rising of South Sea stock… He answered 'that he could not calculate the madness of people'."

[30] He is also quoted as stating, "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men".

[31] Newton's niece

Catherine Conduitt reported that he "lost twenty thousand pounds. Of this, however, he never much liked to hear…"

[32] This was a fortune at the time (equivalent to about £2.4 million in present day terms

[33]), but it is not clear whether it was a monetary loss or an

opportunity cost loss.

[edit] A trading company

The South Seas Company's charter (of 1711) provided it with exclusive access to all of Middle and South America. However, the areas in question were Spanish colonies, and Great Britain was still at war with Spain. Even once a peace treaty had been signed, the South Sea Company was allowed to send only one ship per year to Spain’s American colonies (not one ship per colony; exactly one ship), carrying a cargo of not more than 500 tons. Additionally, it had the right to transport slaves, although steep import duties made the slave trade entirely unprofitable. Nevertheless, relations between the two countries were not good, and the company's trade suffered in two wars between Great Britain and Spain.

[edit] The annual ship

![[icon]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg/20px-Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg.png) | This section requires expansion with: January 2010. (January 2010) |

The company did not undertake a trading voyage to South America until 1717 and made little actual profit. Furthermore, when ties between Spain and Britain deteriorated in 1718 the short-term prospects of the company were very poor. Nonetheless, the company continued to argue that its longer-term future would be extremely profitable.

[edit] The slave asiento

The most commercially significant aspect of the company's monopoly trading rights to the Spanish empire was the 1713

Treaty of Utrecht's slave-trading '

Asiento', which granted the exclusive right to sell slaves in all of the American colonies. The Asiento set a quota of selling 4800 people into slavery per year. Despite problems with speculation, the South Sea Company was relatively successful at

slave trading and meeting its quota (it was unusual for other, similarly chartered companies to fulfill their quotas). According to records compiled by David Eltis and others, during the course of 96 voyages in twenty-five years, the South Sea Company purchased 34,000 slaves of whom 30,000 survived the voyages across the Atlantic.

[34] In other words, approximately 11% of humans transported as slaves died in transport. This was a relatively low mortality rate on the

Middle Crossing.

[35] The company persisted with the slave trade through two wars with Spain and the calamitous 1720 commercial bubble. The company's trade in human slavery peaked during the 1725 trading year, five years after the bubble burst.

[36]

[edit] Arctic whaling

The Greenland Company had been established by Act of Parliament in 1693 with the aim of catching whales in the Arctic. The products of their "whale-fishery" were to be free of Customs and other duties. Partly due to maritime disruption caused by wars with France, the Greenland Company failed financially within a few years. In 1722 Henry Elking published a proposal, directed at the governors of the South Sea Company, that they should resume the "Greenland Trade" and send ships to catch whales in the Arctic. He made very detailed suggestions about how the ships should be crewed and equipped.

[37]

The British Parliament confirmed that a British Arctic "whale-fishery" would continue to benefit by freedom from Customs duties and in 1724 the South Sea Company decided to commence whaling. They had 12 whale-ships built on the River Thames and these went to the Greenland seas in 1725. Further ships were built in later years, but the venture was not successful. At this time there were hardly any experienced whalemen remaining in Britain and the Company had to engage Dutch and Danish whalemen for the key posts aboard their ships, e.g. all commanding officers and harpooners were hired from the

North Frisian island of

Föhr.

[38] Other costs were badly controlled and the catches remained disappointingly few, even though the Company was sending up to 25 ships to

Davis Strait and the

Greenland seas in some years. By 1732 the Company had accumulated a net loss of £177,782 from their 8 years of Arctic whaling.

[39]

The South Sea Company directors appealed to the British government for further support. Parliament had passed an Act in 1732 that extended the duty-free concessions for a further 9 years. In 1733 an Act was passed that also granted a government subsidy to British Arctic whalers, the first in a long series of such Acts that continued and modified the whaling subsidies throughout the eighteenth century. This, and the subsequent Acts, required the whalers to meet conditions regarding the crewing and equipping of the whale-ships that closely resembled the conditions suggested by Elking in 1722.

[40] In spite of the extended duty-free concessions, and the prospect of real subsidies as well, the Court and Directors of the South Sea Company decided that they could not expect to make profits from Arctic whaling. They sent out no more whale-ships after the loss-making 1732 season.

[edit] Government debt after the Bubble

The company continued its trade (when not interrupted by war) until the end of the

Seven Years' War (1756–1763). However, its main function was always managing government debt, rather than trading with the Spanish colonies. The South Sea Company continued its management of the part of the

National Debt until it was abolished in the 1850s.

![[icon]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg/20px-Wiki_letter_w_cropped.svg.png) | This section requires expansion. (October 2009) |

[edit] Officers of the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company had a Governor (generally an honorary position); a Subgovernor; a Deputy Governor and 30 directors (reduced in 1753 to 21).

[41]

-

[edit] See also

- Hancom v Allen (1774) Dickens 498; 21 ER 363

- Trafford v Boehm (3 Atk. 440) Lord Hardwicke, where a trustee laid out trust money in the South Sea annuities, which afterwards sunk in their value; it was considered as a departure from the trust, and the trustee ordered personally to make good the deficiency to the trust-estate.

- Adie v Fennilitteau (1 Cox, 24) by the Lords Commissioners Lord Loughborough, Ashhurst, and Hotham, in April 1783, a trustee laid out trust money in South Sea annuities; they afterwards fell in their price, and though it was in the same fund in which the greatest part of the testator's personal estate was at his death invested, their Lordships held it to be an improper investment; and that the trustee should abide the loss.

- ^ Dale, Richard. The First Crash: Lessons from the South Sea Bubble. London: Princeton University Press, 2004. p. 40.

- ^ British-history.ac.uk

- ^ Carswell p.40, 48-50

- ^ Carswell p. 50-51

- ^ Carswell p.52-54

- ^ Carswell p. 52-54

- ^ Carswell p.54-55

- ^ Carswell p. 56

- ^ Carswell p.57,58

- ^ Carswell p.60-63

- ^ Carswell p. 64-66

- ^ Carswell p. 65-66

- ^ Carswell p. 67

- ^ Carswell p. 66-67

- ^ Carswell p.67-70

- ^ carswell p. 73-75

- ^ Carswell p. 75-76

- ^ Carswell p.88-89

- ^ Carswell p.889-90

- ^ Carswell p.100-102

- ^ Carswell p.102-107

- ^ Carswell p.102-107

- ^ Carswell p.112-113

- ^ Carswell p.114-118

- ^ Carswell p.116-117

- ^ Carswell p.116-117

- ^ Carswell p.138-140

- ^ Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Harriman House Classics 2003), p. 65 & 71.

- ^ Young, Alf (10 February 2009). "Tied up in a sack of snakes and tipped into the Thames". The Herald (Glasgow). http://www.heraldscotland.com/tied-up-in-a-sack-of-snakes-and-tipped-into-the-thames-1.902340. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Spence, Anecdotes, 1820, p. 368.

- ^ John O'Farrell, An Utterly Impartial History of Britain - Or 2000 Years of Upper Class Idiots In Charge (October 22, 2007) (2007, Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-385-61198-5)

- ^ William Seward, Anecdotes of Distinguished Men, 1804

- ^ Computed by share of GDP as an indicator of a society wide economic movement (ie: an aggregate economic phenomena) using Lawrence H. Officer and Samuel H. Williamson, "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.K. Dollar Amount, 1270 to present," MeasuringWorth, March 2011.

- ^ Historycooperative.org

- ^ Paul, Helen. "The South Sea Company’s slaving activities". http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:1UApL7tZw7oJ:www.ehs.org.uk/ehs/conference2004/assets/paul.doc+slave+trade+%22helen+paul%22&hl=en&gl=uk&ct=clnk&cd=1.

- ^ Paul, H.J. (2010). The South Sea Bubble.

- ^ Elking, Henry [1722](1980). A view of the Greenland Trade and whale-fishery. Reprinted: Whitby: Caedmon. ISBN 0-905355-13-X

- ^ Zacchi, Uwe (1986) (in German). Menschen von Föhr. Lebenswege aus drei Jahrhunderten. Heide: Boyens & Co.. p. 13. ISBN 3-8042-0359-0.

- ^ Anderson, Adam [1801](1967). The Origin of Commerce. Reprinted: New York: Kelley.

- ^ Evans, Martin H. (2005). Statutory requirements regarding surgeons on British whale-ships. The Mariner's Mirror 91 (1) 7-12.

- ^ See, for 1711-21, J Carswell, South Sea Bubble (1960) 274-9; and for 1721-1840, see British Library, Add. MSS, 25544-9.

[edit] References

- Historical

- C. Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841)

- Carswell, John (1960), The South Sea Bubble, London: Cresset Press

- Cowles, Virginia (1960), The Great Swindle: The Story of the South Sea Bubble, New York: Harper

- Dale, Richard S.; et al. (2005), "Financial markets can go mad: evidence of irrational behaviour during the South Sea Bubble", Economic History Review 58 (2): 233–271, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00304.x

- Hoppit, Julian. (2002) "The Myths of the South Sea Bubble," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, (2002) Vol. 12 Issue 1, pp 141–165 in JSTOR

- Paul, Helen Julia (2010) The South Sea Bubble: an economic history of its origins and consequences, Routledge Explorations in Economic History, Routledge, London.

- Shea, Gary S. (2007), "Understanding financial derivatives during the South Sea Bubble: The case of the South Sea subscription shares", Oxford Economic Papers 59 (Supplement 1): i73-i104, doi:10.1093/oep/gpm031

- Temin, Peter; Voth, Hans-Joachim (2004), "Riding the South Sea Bubble", American Economic Review 94 (5): 1654–1668, doi:10.1257/0002828043052268

- Viscount Erleigh "The South Sea Bubble", Peter Davis, 1933

- Fiction

- Liss, David (2000), A Conspiracy of Paper, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-375-50292-0. Novel set around the South Sea Company bubble.

- Goddard, Robert (2000), Sea Change, London: Bantam Press, p. 416, ISBN 0-593-04667-6. Novel set against the background of the South Sea bubble.

[edit] External links