From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Austrian School | |

|---|---|

| |

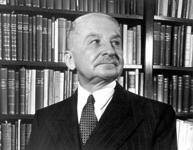

| Born | 29 September 1881 Lemberg, Galicia, Austria-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukraine) |

| Died | 10 October 1973 (aged 92) New York City, New York, USA |

| Institution | University of Vienna (1919-1934) Institut Universitaire des Hautes Études Internationales, Geneva, Switzerland (1934-1940) New York University (1945-1969) |

| Influences | Kant, Bastiat, Böhm-Bawerk, Brentano, Husserl, Menger, Say, Turgot, Weber, Wieser, Wicksell, Lord Overstone[1] |

| Influenced | Allais, Anderson, Bauer, Block, Buchanan, Friedman, Hayek, Hazlitt, Hicks, Hoppe, Huerta de Soto, Hutt, Kirzner, Lachmann, Lange, Paul, Raico, Reisman, Robbins, Rockwell, Rothbard, Salerno, Schiff, Schumpeter, Schutz, Sennholz, Simons, Smith, Woods |

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Biography

| Part of a series on the |

| Austrian School |

|---|

[edit] Early life

Coat of arms of Ludwig von Mises' great-grandfather, Mayer Rachmiel Mises, awarded upon his 1881 ennoblement by Franz Joseph I of Austria

In 1900, he attended the University of Vienna,[4] becoming influenced by the works of Carl Menger. Mises' father died in 1903, and in 1906 Mises was awarded his doctorate from the school of law.

[edit] Subsequent professional and personal life

In the years from 1904 to 1914, Mises attended lectures given by the prominent Austrian economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. There, he developed friendships not only with Menger and Böhm-Bawerk, but also prominent sociologist Max Weber.[5] Mises taught as a Privatdozent at the Vienna University in the years from 1913 to 1934 while formally serving as secretary at the Vienna Chamber of Commerce from 1909 to 1934. In these roles, he became one of the closest economic advisers of Engelbert Dollfuss, the austrofascist but strongly anti-Nazi Austrian Chancellor,[6] and later to Otto von Habsburg, the Christian democratic politician and claimant to the throne of Austria (which had been legally abolished in 1918).[7] Friends and students of Mises in Europe included Wilhelm Röpke and Alfred Müller-Armack (influential advisors to German chancellor Ludwig Erhard), Jacques Rueff (monetary advisor to Charles de Gaulle), Gottfried Haberler (later a professor at Harvard), Lord Lionel Robbins (of the London School of Economics), and Italian President Luigi Einaudi.[8]Economist and political theorist F. A. Hayek first came to know Mises while working as Mises' subordinate at a government office dealing with Austria's post-World War I debt. Hayek wrote, "there I came to know him mainly as a tremendously efficient executive, the kind of man who, as was said of John Stuart Mill, because he does a normal day's work in two hours, always has a clear desk and time to talk about anything. I came to know him as one of the best educated and informed men I have ever known..."[9] According to Mises' student Murray Rothbard, Hayek's development of Mises' theoretical work on the business cycle later earned Hayek the 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (shared with Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal).[10]

In 1934, Mises left Austria for Geneva, Switzerland, where he was a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies until 1940. While in Switzerland, Mises married Margit Herzfeld Serény, a former actress and the widow of the Hungarian aristocrat Ferdinand Serény. His step-daughter Gitta Sereny (1921-2012) subsequently came to be known for her interviews and profiles of controversial figures, including Mary Bell, who was convicted in 1968 of killing two children when she herself was a child, and Franz Stangl, the commandant of the Treblinka extermination camp.[11]

In 1940, fearing the prospect of Germany taking control over Switzerland, Mises left Europe and emigrated to New York City.[12] There he became a visiting professor at New York University. He held this position from 1945 until his retirement in 1969, though he was not salaried by the university. Instead, businessmen such as Lawrence Fertig funded him and his work. For part of this period, Mises worked on currency issues for the Pan-Europa movement led by a fellow NYU faculty member and Austrian exile, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi.[13] In 1947, Mises became one of the founding members of the Mont Pelerin Society. Despite fleeing Europe, Mises is credited for having an influential role in the economic reconstruction of Europe after World War II through his professional relationships with Ludwig Erhard, Charles de Gaulle and Luigi Einaudi.[14]

In America, Mises' work first influenced that of economists such as Benjamin Anderson, Leonard Read and Henry Hazlitt, but writers such as former radical Max Eastman, legal scholar Sylvester J. Petro, and novelist Ayn Rand were also among his friends and admirers. His American students included Israel Kirzner, Hans Sennholz, Ralph Raico, Leonard Liggio, George Reisman and Murray Rothbard.[15] Mises later received an honorary doctorate from Grove City College.

Mises contributed articles to American Opinion, the journal of the John Birch Society, and was a member of its Editorial Advisory Board.[16][17]

Despite his growing fame, Mises listed himself plainly in the New York phone directory and welcomed students into his home.[18] He retired from teaching at the age of 87, then the oldest active professor in America.[19] Mises died at the age of 92 at St. Vincent's hospital in New York. His body is buried at Ferncliff Cemetery, in Hartsdale, New York. Following his death, his entire library (and his personal desk) was donated to Hillsdale College where it is available for student and public use.

[edit] Contributions to economics

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

- monetary economics and inflation;

- the differences between government controlled economies and free markets.

According to Mises, socialism must fail, as demand cannot be known without prices. Therefore, socialist waste of capital goods is as chronic as the incentives for production and retention of capital are low, while capital goods are coercively monopolised by a dysfunctional State operating with only the data pertaining to interpersonal comparisons of utility, as per democratic production. These data are not sufficient for economic calculation, and therefore are not sufficient for efficient use and allocation of capital. Capital's place in a free market is ordained by the prices set by private owners of the means of production, who keep capital where its production is remunerated best by consumers, and who liquidate it and pass it to other uses if production is bankrupt. In socialism, such means for liquidation of capital goods, and the passage or maintenance of the means of production across extremely diverse applications throughout the divisions of labour according to the expense or cheapness of bidding capital away from vital production, is simply not present.

Mises' criticism of socialist paths of economic development is well-known, such as in his 1922 work Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis:

The only certain fact about Russian affairs under the Soviet regime with regard to which all people agree is: that the standard of living of the Russian masses is much lower than that of the masses in the country which is universally considered as the paragon of capitalism, the United States of America. If we were to regard the Soviet regime as an experiment, we would have to say that the experiment has clearly demonstrated the superiority of capitalism and the inferiority of socialism.[21]These arguments were elaborated on by subsequent Austrian economists such as Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek[22] and students such as Hans Sennholz.

In Interventionism, An Economic Analysis (1940), Ludwig von Mises wrote:

The usual terminology of political language is stupid. What is 'left' and what is 'right'? Why should Hitler be 'right' and Stalin, his temporary friend, be 'left'? Who is 'reactionary' and who is 'progressive'? Reaction against an unwise policy is not to be condemned. And progress towards chaos is not to be commended. Nothing should find acceptance just because it is new, radical, and fashionable. 'Orthodoxy' is not an evil if the doctrine on which the 'orthodox' stand is sound. Who is anti-labor, those who want to lower labor to the Russian level, or those who want for labor the capitalistic standard of the United States? Who is 'nationalist,' those who want to bring their nation under the heel of the Nazis, or those who want to preserve its independence?After the fall of the Soviet Union Robert Heilbroner, a longtime advocate of Scandinavian-style social democracy, said that "It turns out, of course, that Mises was right" about the impossibility of socialism. "Capitalism has been as unmistakable a success as socialism has been a failure. Here is the part that's hard to swallow. It has been the Friedmans, Hayeks, and von Miseses who have maintained that capitalism would flourish and that socialism would develop incurable ailments."[23]

Mises developed the theory of the 'sovereignty of the consumer' in a free-market economy; in his view, the consumer ultimately dictates everything that happens. This argument was set out in Human Action:

The captain is the consumer…the consumers determine precisely what should be produced, in what quality, and in what quantities…They are merciless egoistic bosses, full of whims and fancies, changeable and unpredictable. For them nothing counts other than their own satisfaction…In their capacity as buyers and consumers they are hard-hearted and callous, without consideration for other people…Capitalists…can only preserve and increase their wealth by filling best the orders of the consumers… In the conduct of their business affairs they must be unfeeling and stony-hearted because the consumers, their bosses, are themselves unfeeling and stony-hearted.[24]

[edit] Criticisms

Milton Friedman considered Mises inflexible in his thinking:The story I remember best happened at the initial Mont Pelerin meeting when he got up and said, "You're all a bunch of socialists." We were discussing the distribution of income, and whether you should have progressive income taxes. Some of the people there were expressing the view that there could be a justification for it.

Another occasion which is equally telling: Fritz Machlup was a student of Mises's, one of his most faithful disciples. At one of the Mont Pelerin meetings, Machlup gave a talk in which I think he questioned the idea of a gold standard; he came out in favor of floating exchange rates. Mises was so mad he wouldn't speak to Machlup for three years. Some people had to come around and bring them together again. It's hard to understand; you can get some understanding of it by taking into account how people like Mises were persecuted in their lives.[25]Within the post-WWII mainstream economics establishment, Mises suffered severe personal rejection: for example, in a 1957 review of his book The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality, The Economist said of von Mises: "Professor von Mises has a splendid analytical mind and an admirable passion for liberty; but as a student of human nature he is worse than null and as a debater he is of Hyde Park standard."[26] Conservative commentator Whittaker Chambers published a similarly negative review of that book in the National Review, stating that Mises's thesis that anti-capitalist sentiment was rooted in "envy" epitomized "know-nothing conservatism" at its "know-nothingest."[27] Economic historian Bruce Caldwell writes that in the mid-20th century, with the ascendance of positivism and Keynesianism, Mises came to be perceived by many as the "archetypal 'unscientific' economist."[28]

In a 1978 interview, Friedrich Hayek said about his book Socialism: "At first we all felt he was frightfully exaggerating and even offensive in tone. You see, he hurt all our deepest feelings, but gradually he won us around, although for a long time I had to – I just learned he was usually right in his conclusions, but I was not completely satisfied with his argument." (Hayek's critique of central planning never incorporated Mises' contention that prices as an indicator of scarcity can only arise in monetary exchanges among responsible owners, a particular case of the universal economic law that value judgements are utterly dependent on property rights constraints.)[29]

Murray Rothbard, who studied under Mises, agrees he was uncompromising, but disputes reports of his abrasiveness. In his words, Mises was "unbelievably sweet, constantly finding research projects for students to do, unfailingly courteous, and never bitter" about the discrimination he received at the hands of the economic establishment of his time.[30]

After his death, his wife quoted a passage that Mises had written about Benjamin Anderson, and said that it best described Mises' own personality: "His most eminent qualities were his inflexible honesty, his unhesitating sincerity. He never yielded. He always freely enunciated what he considered to be true. If he had been prepared to suppress or only to soften his criticisms of popular, but irresponsible, policies, the most influential positions and offices would have been offered him. But he never compromised."[31]

A number of critics of Mises, including philosopher Herbert Marcuse, economist J. Bradford DeLong[32] and sociologist Richard Seymour,[33] have criticized Mises for writing approvingly of Italian fascism, especially for its suppression of leftist elements.[34] Von Mises wrote in Liberalism, a book published in 1927:

Mises biographer and supporter Jörg Guido Hülsmann calls the criticism that Mises supported fascism "absurd", pointing to the rest of the quote that called fascism dangerous and described as a "fatal error" the view that it was more than an "emergency makeshift" against the threat of communism.[36]It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error.[35]

[edit] Bibliography

- The Theory of Money and Credit (1912, enlarged US edition 1953)

- Nation, State, and Economy (1919)

- "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" (1920) (article)

- Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis (1922, 1932, 1951)

- Liberalismus (1927, 1962 – translated into English, with the new title The Free and Prosperous Commonwealth)

- A Critique of Interventionism (1929)

- Epistemological Problems of Economics (1933, 1960)

- Memoirs (1940)

- Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (1941, 1998)

- Omnipotent Government: The Rise of Total State and Total War (1944)

- Bureaucracy (1944, 1962)

- Planned Chaos (1947, added to 1951 edition of Socialism)

- Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949, 1963, 1966, 1996)

- Planning for Freedom (1952, enlarged editions in 1962, 1974, and 1980)

- The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality (1956)

- Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution (1957)

- The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science (1962)

- The Historical Setting of the Austrian School of Economics (1969)

- Notes and Recollections (1978)

- The Clash of Group Interests and Other Essays (1978)

- On the Manipulation of Money and Credit (1978)

- The Causes of the Economic Crisis, reissue

- Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow (1979, lectures given in 1959)

- Money, Method, and the Market Process (1990)

- Economic Freedom and Interventionism (1990)

- The Free Market and Its Enemies (2004, lectures given in 1951)

- Marxism Unmasked: From Delusion to Destruction (2006, lectures given in 1952)

- Ludwig von Mises on Money and Inflation (2010, lectures given in the 1960s)

[edit] See also

|

|

[edit] References

*Note regarding personal names: 'Edler' (in English: 'noble') is a German title, in rank similar to that of a baronet. It is not a first or middle name. The female form is 'Edle'. Similarly, below, 'Ritter' is German for 'knight' and 'Graf' for 'count'.- ^ Roger W. Garrison, Ludwig Edler von Mises, in: David Glasner (ed.), Business Cycles and Depressions, New York: Garland Publishing Co., 1997, pp. 440-42.

- ^ Hulsmann, Jörg Guido (2007). Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism. Ludwig von Mises Institute. pp. 3–9. ISBN 1-933550-18-X.

- ^ Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, "The Cultural Background of Ludwig von Mises", The Ludwig von Mises Institute, page 1

- ^ Von Mises, Ludwig; Goddard, Arthur (1979). Liberalism: a socio-economic exposition (2 ed.). ISBN 0-8362-5106-7.

- ^ Mises, Ludwig von, The Historical Setting of the Austrian School of Economics, Arlington Houise, 1969, reprinted by the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1984, p. 10, Rothbard, Murray, The Essential Ludwig von Mises, 2nd printing, Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1983, p. 30.

- ^ "The Free Market: Meaning of the Mises Papers, The". Mises.org. http://mises.org/freemarket_detail.aspx?control=137. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ^ Mises, Margit von, My Years with Ludwig von Mises, Arlington House, 1976, 2nd enlarged edit., Center for Future Education, 1984.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray, Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1988, p. 67.

- ^ Mises, Margit von, My Years with Ludwig von Mises, Arlington House, 1976, 2nd enlarged edit., Center for Future Education, 1984, pp. 219-220.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray, Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1988, p. 68.

- ^ Neild, Barry. "Gitta Sereny dies at 91", The Guardian, 18 June 2012.

- ^ Hulsmann, Jorg Guido (2007). Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. xi. ISBN 1-933550-18-X.

- ^ Coudenhove-Kalergi, Richard Nikolaus, Graf von (1953). An idea conquers the world. London: Hutchinson. p. 247.

- ^ Doherty, Brian, "Radicals for Capitalism", PublicAffairs, 2007, p.10.

- ^ On Mises' influence, see Rothbard, Murray, The Essential Ludwig von Mises, 2nd printing, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1983; on Eastman's conversion "from Marx to Mises," see Diggins, John P., Up From Communism Harper & Row, 1975, pp. 201–233; on Mises's students and seminar attendees, see Mises, Margit von, My Years with Ludwig von Mises, Arlington House, 1976, 2nd enlarged edit., Center for Future Education, 1984.

- ^ Gordon, David. "Mises and the Right". http://www.lewrockwell.com/blog/lewrw/archives/18540.html. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ^ Wells, Sam. "An Interview with Sam Wells". http://laissez-fairerepublic.com/samwells.htm. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ^ Reisman, George, Capitalism: a Treatise on Economics, "Introduction," Jameson Books, 1996; and Mises, Margit von, My Years with Ludwig von Mises, 2nd enlarged edit., Center for Future Education, 1984, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray, Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1988, p.61.

- ^ For example, Murray Rothbard, a leading Austrian school economist, has written that, by the 1920s, "Mises was clearly the outstanding bearer of the great Austrian tradition." Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero, the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis by Ludwig von Mises.

- ^ F. A. Hayek, (1935) who also wrote the introduction to "Socialism" and went on to author "The Nature and History of the Problem" and "The Present State of the Debate," in F. A. Hayek, ed. Collectivist Economic Planning, pp. 1–40, 201–43.

- ^ Reason.com, "The Man Who Told the Truth" Reason, 1990. Retrieved on 4 April 2009.

- ^ 'Human Action' chap. 15, sect. 4

- ^ "Best of Both Worlds (Interview with Milton Friedman)". Reason. June 1995. http://www.reason.com/news/show/29691.html.

- ^ "Liberalism in Caricature", The Economist

- ^ Quoted in Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography, (Random House, New York, 1997), p. 500. ISBN 978-0-375-75145-5.

- ^ Caldwell, Bruce (2004). Hayek's Challenge. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 125–6. ISBN 978-0-226-09191-4.

- ^ UCLA Oral History (Interview with Friedrich Hayek), American Libraries/Internet Archive, 1978. Retrieved on 4 April 2009 (Blog.Mises.org), source with quotes

- ^ Murray Rothbard, "The Future of Austrian Economics", http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KWdUIuID8ag

- ^ Ludwig von Mises, Israel M. Kirzner, (Library of Modern Thinkers, 2001), page 31

- ^ See "Dictatorships and Double Standards: Jeet Heer Has a Ludwig Von Mises Quote..."

- ^ Richard Seymour, The Meaning of Cameron, (Zero Books, John Hunt, London, 2010), p. 32. ISBN 1846944562

- ^ Ralph Raico, "Mises on Fascism, Democracy, and Other Questions, Journal of Libertarian Studies (1996) 12:1 pp 1-27

- ^ Ludwig von Mises, "Liberalism" (1927)

- ^ Jörg Guido Hülsmann, Mises: the last knight of liberalism (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007), p. 560. ISBN 193355018X.

[edit] Further reading

- Butler, Eamonn, Ludwig von Mises – A Primer, Institute of Economic Affairs (2010)

- Doherty, Brian, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (2007)

- Ebeling, Richard M. Political Economy, Public Policy, and Monetary Economics: Ludwig von Mises and the Austrian Tradition, (London/New York: Routledge, 2010) 354 pages, ISBN 978-0-415-77951-7.

- Ebeling, Richard M. "Ludwig von Mises: The Political Economist of Liberty, Part II", (The Freeman, June 2006)

- Ebeling, Richard M. "Ludwig von Mises: The Political Economist of Liberty, Part I", (The Freeman, May 2006)

- Ebeling, Richard M. "Ludwig von Mises and the Vienna of His Time, Part II", (The Freeman, April 2005)

- Ebeling, Richard M. "Ludwig von Mises and the Vienna of His Time, Part I", (The Freeman, March 2005)

- Ebeling, Richard M. "Austrian Economics and the Political Economy of Freedom", (The Freeman, June 2004)

- Gordon, David (2011-02-23) Mises's Epistemology, Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Hülsmann, Jörg Guido. Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism (Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institut, 2007) ISBN 978-1-933550-18-3

- Kirzner, Israel M. Ludwig von Mises: the man and his economics (2001)

- Paul, Ron. "Mises and Austrian economics: A personal view" The Ludwig von Mises Institute of Auburn University (1984), 31 pages.

- Rothbard, Murray N. "Mises. Ludwig Edler von," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 1987, v. 3, pp. 479–80.

- Von Mises, Margit. My Years With Ludwig von Mises, Arlington House, 1976, rereleased in 1984 by Libertarian Press. ISBN 0-915513-00-5

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Ludwig von Mises |

- Ludwig von Mises Institute Europe

- Mises.org, Ludwig von Mises Institute USA

- Mises.de, Books and Articles in the original German versions by Ludwig von Mises and other Authors of the Austrian School

- Ludwig von Mises at the Open Directory Project

- Audio of von Mises subtitled in Spanish and English "Do wage earners and their employers have interests in conflict?"

- "A Tribute to Ludwig Von Mises". A list of works by and on Ludwig Von Mises by the Foundation for Economic Education

- Ludwig von Mises at Find a Grave

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

No comments:

Post a Comment