Ben Broadbent, deputy governor of the Bank of England, gave a speech this week in which I agreed with some (but by no means all) of what he said.

His argument was summarised in this statement:

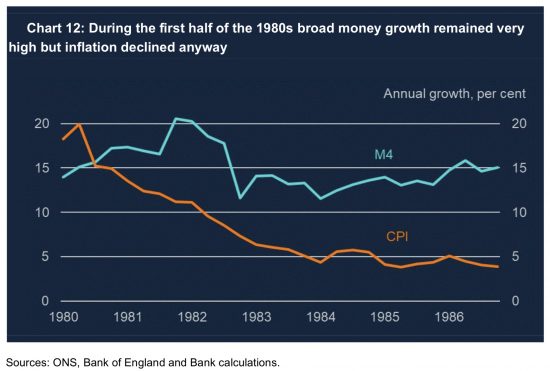

Certainly the very strongest claims – that QE inevitably leads to rapid growth of commercial bank deposits (M4), on a par with that in the central bank's balance sheet; and that this, in turn, inevitably leads to excessive inflation – are not well supported by the evidence. Broad money grew more than twice as rapidly in the first fifteen years of inflation targeting (when there was no QE) than in the decade or so after the financial crisis (when there was lots). And average inflation, in both periods, was close to 2%.

In effect, the argument he made was that the creation of new money by the Bank of England under cover of the quantitative easing process, did not result in inflation.

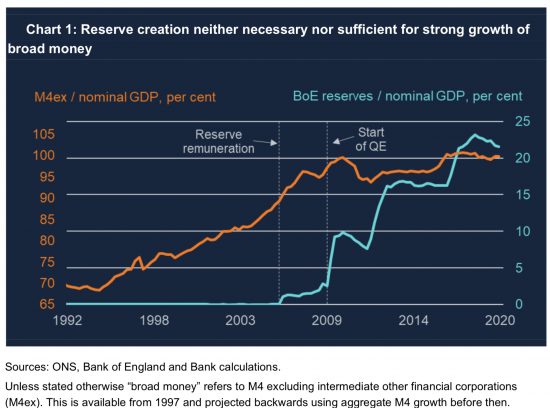

He developed this thesis using several charts:

The argument made, based on this chart, is that the growth in central bank, base, narrow or reserve account money (they are, effectively, all the same thing, with all of it being constrained within the Bank of England inter-bank settlement cycle through the central bank reserve accounts) is not related to the growth in commercial bank or broad money, which is what is actually used in the economy in which we all operate. It's a notable and appropriate suggestion.

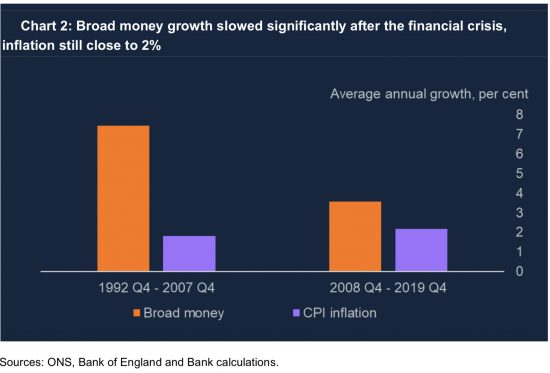

Broadbent reinforced the claim by suggesting that the global financial crisis changed the pattern of money creation, but doing so did not result in inflation:

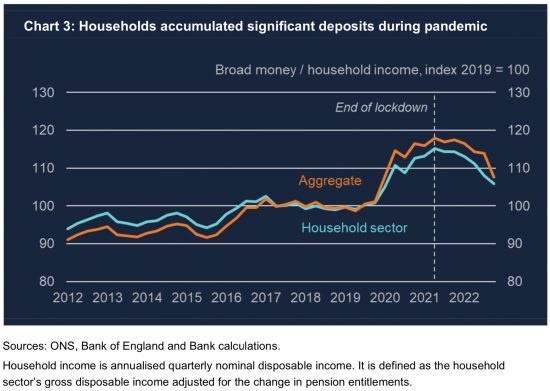

The point he then noted was that the impact of Covid was that some in society did save using broad or commercial bank-created money:

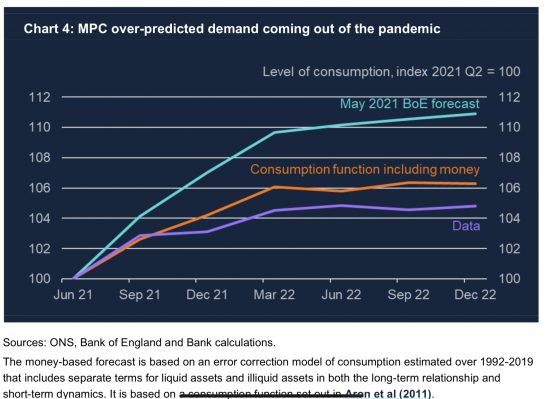

What the Bank then expected was that people would then spend that pent-up money. This is what those who claim the QE created inflation also suggest. However, as Broadbent notes, that tendency to spend was much smaller than expected:

Broadbent then used a New Keynesian, and so deeply neoclassical, explanation for what did happen in the macroeconomy. From this he concluded that, firstly, it was external shocks that created this inflation and, secondly, like Huw Pill, he thinks we must accept that we are worse off as a result. I do not agree with the reasons he gave, but what I do agree with is his conclusion that central bank money creation, let alone broad money creation, is not closely (if very much at all) linked to inflation. His Chart 12 provided support:

Money supply growth was high. Inflation was not. At the very least, the velocity of circulation of money dropped dramatically. The obvious explanation for that is growing inequality. He did not say so.

Where I do agree with Ben Broadbent is that there is no obvious evidence that QE did in any way result in inflation. I think it is time to dismiss that argument.