/ From his BlogSpot

Transfinancial Economics is similar to what is referred to here as Cybernetic Economics, or Cyber Communism. However, TFE starts within the Capitalist System in a way which is both pragmatic, and progressive. It can though ofcourse lead to a more "advanced" society that is more in line with Socialism and Communism but with a very high degree of democracy as opposed to some totalitarian state devoid of human rights. See https://wiki.p2pfoundation.net/Transfinancial_Economics

I shall be elaborating on the following theses:

- The inability of 20th century socialism to progress to communism led to the crisis of the USSR.

- Communism requires a definite stage of development of technology.

- This stage was only reached at the very end of the 20th century.

- But this problem of technical adequacy can not be understood in just humanist terms of ‘plenty’ or in terms of ‘the realm of necessity’.

1 What is a mode of production

Is Socialism a mode of production?The standard account, derived from Stalin, is that a mode of production is a combination of productive forces and production relations:

Mode of production = productive forces + production relations

This was sumarised by Stalin as

the productive forces are only one aspect of production, only one aspect of the mode of production, an aspect that expresses the relation of men to the objects and forces of nature which they make use of for the production of material values. Another aspect of production, another aspect of the mode of production, is the relation of men to each other in the process of production, men’s relations of production. [19]

This has been the orthodoxy, but I think it is wrong. Another meaning of the phrase mode of production is, according to Marx, the mode of material production. This mode of production, according to Marx’s 1857 preface, conditions the social and political life. The relations of production only have to be appropriate to the productive forces.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life.[12]

This conception had been expressed by Marx ten years earlier in his pithy phrase :

The hand mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam mill, society with the industrial capitalist. [11]

In this conception the essential feature of capitalist production is that it is machine industry, production by means of (steam) powered machines. But this should give us pause to think, for is not socialism also characterised by machine production, by the use of artificial forms of energy?Recall that Lenin expressed this very idea when he gave the following equation:

Socialism = Soviet power + Electrification

Since the difference between steam power and electrical power is secondary, and we know that capitalist economies also use electricity, the important point is that capitalism and socialism share the same mode of production.

We can summarize this in two equations defining the mode of production:

Capitalist mode of production = powered machine industry.

Socialist mode of production = electric machine industry.

So the socialist mode of production is a subset of the machine mode of production – that which uses nationwide electric grids. Hence the first aim of the USSR was to set up GOLERO the electricity plan.

Socialism and capitalism differ not so much in mode of production as in the social relations.

Capitalist production relations =

Commodity production +

Private ownership +

Wage labour+

Market anarchy

Private ownership +

Wage labour+

Market anarchy

Socialist production relations =

Commodity form of consumer goods+

Public ownership +

Wage labour +

Planning

The significant differences are firstly that socialist production relations can restrict the commodity form to the consumer goods market. Within the publicly owned sector there is no change in ownership as means of production go from one state factory to another – hence these goods are not commodities. Secondly the socialist economy substitutes public for private ownership. Third it replaces the anarchic market with directive planning. These are differences in production relations but not in the mode of production.Public ownership +

Wage labour +

Planning

2 Marx vs USSR on Communism

Marx, in Critique of the Gotha Programme presents a three stage process of transition to communism.- Capitalism

- First stage communism No commodities or money, no private owners, payment in labour tokens according to physical work done. Public services paid for by an income tax on labour incomes.

- Second stage communism Payment according to need, large families etc get higher incomes.

Now let me contrast this scheme with what became the Soviet orthodoxy derived variously from the Bukharin text mentioned earlier and from Stalin[18]. Again we have a 3 stage model

- Capitalism

- Socialism: Commodities and money are kept, state+coop ownership, payment in money wages according to work done and status of work ( male jobs paid more than female ), indirect taxes on sales not income tax provide the main state revenue.

- Communism: Commodity production replaced by barter, free distribution of many goods, full state ownership.

3 Why did USSR not reach communism?

The material and technical basis of communism will be built up by the end of the second decade (1971-80), ensuring an abundance of material and cultural values for the whole population ; Soviet society will come close to a stage where it can introduce the principle of distribution according to needs, and there will be a gradual transition to one form of ownership-public ownership . Thus, a communist society will in the main be built in the U.S.S.R . The construction of communist society will be fully completed in the subsequent period. (Programme CPSU 1960)

The USSR in 1960 was still very ambitious. They had a very optimistic time table for overtaking US and in many key industries this goal was in fact achieved. The transition to communism was seen solely in terms of quantity of output not in terms of changed social relations. A key technical development was still seen to be electrification: Electrification, which is the pivot of the economic construction of communist society,plays a key role in the development of all economic branches and in the effecting of all modern technological progress. It is therefore important to ensure the priority development of electric power output. It is notable that no particular attention was paid to information technology as an enabling technology for communism.How well did they actually do? Well table 1 shows that in their key goal of electricity the USSR was already by 1990 doing better than the leading European capitalist countries had achieve a quarter century later.

Table 1: Comparison of power available to different economies converted into human labour effort equivalents per head of population. Assumption is that a manual worker could do 216 KWh per year of work.

| year | Gwh | human labour | |

| equiv per head | |||

| China | 2014 | 5665000 | 19.2 |

| US | 2014 | 4331000 | 63.1 |

| EU | 2014 | 3166000 | 19.7 |

| USSR | 1990 | 1728000 | 27.3 |

| USSR | 1940 | 48000 | 1.2 |

| USSR | 1931 | 8800 | 0.3 |

| Russia | 1913 | 1300 | 0.0 |

| GB | 2014 | 338000 | 24.8 |

| GB | 1907 | 61320 | 7.3 |

What about food production?

How well did the USSR achieve its goals there?

Pretty well according to Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of late Soviet with UK, Brazil and US annual per capita output of major protein foods. Note that for all categories the late USSR had better figures. Sources [14], FAOSTAT and USDA databases.

| Year | Meat | Milk | Eggs | |

| Kg | Kg | Units | ||

| USSR | 1988 | 69 | 375 | 299 |

| Brazil | 1988 | 49 | 96 | 163 |

| UK | 1988 | 55 | 265 | 201 |

| USA | 1988 | 58 | ||

| USA | 1990 | 236 | ||

| USA | 1995 | 259 |

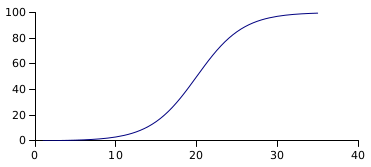

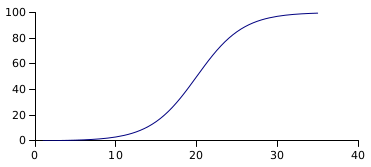

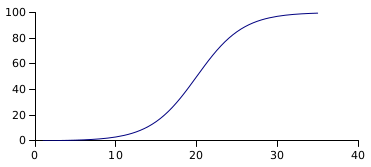

But Soviet growth slowed down. The Kruschev era had assumed continued exponential growth and had defined communism in terms of achieving exponential growth. The assumption of exponential growth was unrealistic. Actual growth can not be exponential for long, it inevitably starts to slow down. Actual growth tends to follow a logistic curve like this.

c

Khrushchev s Communism downplayed social change

Under communism there will be no classes, and the socio-economic and cultural distinctions, and differences in living conditions, between town and countryside will disappear ; the countryside will rise to the level of the town in the development of the productive forces and the nature of work, the forms of production relations, living conditions and the well-being of the population. (Programme CPSU 1960)But the concrete programme gave no measures to abolish classes or abolish money and commodities. When the impossibility of continued 10% growth made itself felt, this was seen as the failure of communism, since social change had not been at its core. If society was not moving forward, it failed to morally inspire people and by the late 1980s communists could not resist the pressures from capitalist ideology.

4 Bourgeois theorists said Communism impossible

Von-Mises

Only money provides a rational basis for comparing costs Calculation in terms of labour time impractical because of the millions of equations that would need to be solved.Hayek

Market is like a telephone system exchanging information to tie up economy Only the market can solve problem of dispersed informationThere was some limited truth in this. Marx s communism was not yet possible in 1960 due to limitations in information processing. Marx s Communism stage 1 assumed

- No money

- Calculation in terms of labour time and use values

- Payment in labour credits

Money was still needed for economic calculation even in the planned sector. There was a problem of aggregation in planning which required setting monetary objectives. There was an inability to handle disaggregated plans at all Union level. Money was still needed for wage payments. But cash led to black markets, corruption and pressure to restore capitalist relations.

5 Key developments in productive forces since 1960

But since 1960 there have been a set of technical advances that allow us to remove these old objections to communist economics.Internet

which allows real-time cybernetic planning and can solve the problem of dispersed information – Hayeks key objection

Big-data

allows concentration of the information needed for planning.

Super-computers

can solve the millions of equations in seconds – von Mises objection

Electronic payment cards

allow replacement of cash with non transferable labour credits.

Computational complexity

How easy is it to solve the millions of equations. There are some problems that become computationally intractable even for the largest computers. Is economic planning or the use of labour accounting like that?No it is not. In a series of papers[2,6,5,4,9,8], Allin Cottrell, Greg Michaelson and I have shown that the computational complexity of computing labour values for an entire economy with N distinct products grows as Nlog(N) This means that it is highly tractable and easily solved by modern computers

Direct Democracy

It is also possible to harness computer networks and mobile phone voting to allow direct democratic control by the mass of the population over the economy. This allows major strategic decisions taken democratically, questions like: How much labour to devote to education? How much to health, pensions, sick? How much to environmental protection? How much to national defence? How much to new investment?All this can be done by direct voting using computers or mobile phones every year. We have prototyped software to aggregate the wishes of the public this way[7,15,16,3].

Equivalence

Marx s principle was that non-public goods should be distributed on the equivalence principle – you get back in goods the same amount of labour – after tax – that you perform. Hence goods are priced in labour hours. Cybernetic feedback from sales to the plan adjusts output to consumer needs as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cybernetic planning

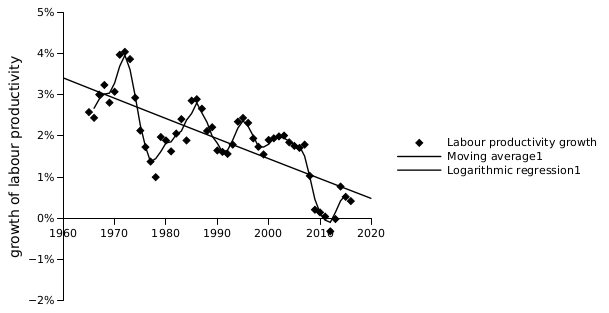

Marx argued that calculation in terms of labour time would lead to greater efficiency. The wages system undervalues the real social cost of labour and deters the use of the most modern machinery. Transition to communist calculation will lead to the rational use of labour time, and faster growth of labour productivity.

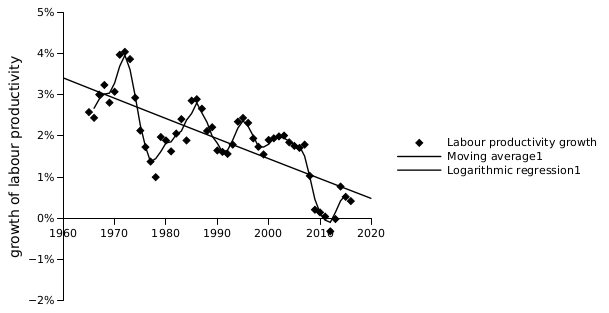

Figure 2: The growth of labour productivity has been shrinking over the last half century in the UK. Growth rates computed as moving average over last 5 years fron ONS data for output per worker for the whole economy.

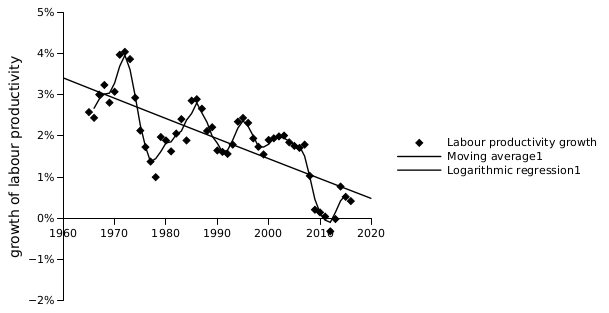

Figure 3: The decline in productivity growth is an international phenomonon. Data obtained from

I shall be elaborating on the following theses:

The standard account, derived from Stalin, is that a mode of production is a combination of productive forces and production relations:

Mode of production = productive forces + production relations

This was sumarised by Stalin as

Recall that Lenin expressed this very idea when he gave the following equation:

Socialism = Soviet power + Electrification

Since the difference between steam power and electrical power is secondary, and we know that capitalist economies also use electricity, the important point is that capitalism and socialism share the same mode of production.

We can summarize this in two equations defining the mode of production:

Capitalist mode of production = powered machine industry.

Socialist mode of production = electric machine industry.

So the socialist mode of production is a subset of the machine mode of production – that which uses nationwide electric grids. Hence the first aim of the USSR was to set up GOLERO the electricity plan.

Socialism and capitalism differ not so much in mode of production as in the social relations.

Now let me contrast this scheme with what became the Soviet orthodoxy derived variously from the Bukharin text mentioned earlier and from Stalin[18]. Again we have a 3 stage model

How well did they actually do? Well table 1 shows that in their key goal of electricity the USSR was already by 1990 doing better than the leading European capitalist countries had achieve a quarter century later.

Was this enough power for communism?

What about food production?

How well did the USSR achieve its goals there?

Pretty well according to Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of late Soviet with UK, Brazil and US annual per capita output of major protein foods. Note that for all categories the late USSR had better figures. Sources [14], FAOSTAT and USDA databases.

Was this enough food for communism?

But Soviet growth slowed down. The Kruschev era had assumed continued exponential growth and had defined communism in terms of achieving exponential growth. The assumption of exponential growth was unrealistic. Actual growth can not be exponential for long, it inevitably starts to slow down. Actual growth tends to follow a logistic curve like this.

c

But the concrete programme gave no measures to abolish classes or abolish money and commodities. When the impossibility of continued 10% growth made itself felt, this was seen as the failure of communism, since social change had not been at its core. If society was not moving forward, it failed to morally inspire people and by the late 1980s communists could not resist the pressures from capitalist ideology.

There was some limited truth in this. Marx s communism was not yet possible in 1960 due to limitations in information processing. Marx s Communism stage 1 assumed

Money was still needed for economic calculation even in the planned sector. There was a problem of aggregation in planning which required setting monetary objectives. There was an inability to handle disaggregated plans at all Union level. Money was still needed for wage payments. But cash led to black markets, corruption and pressure to restore capitalist relations.

No it is not. In a series of papers[2,6,5,4,9,8], Allin Cottrell, Greg Michaelson and I have shown that the computational complexity of computing labour values for an entire economy with N distinct products grows as Nlog(N) This means that it is highly tractable and easily solved by modern computers

All this can be done by direct voting using computers or mobile phones every year. We have prototyped software to aggregate the wishes of the public this way[7,15,16,3].

Figure 1: Cybernetic planning

Marx argued that calculation in terms of labour time would lead to greater efficiency. The wages system undervalues the real social cost of labour and deters the use of the most modern machinery. Transition to communist calculation will lead to the rational use of labour time, and faster growth of labour productivity.

Figure 2: The growth of labour productivity has been shrinking over the last half century in the UK. Growth rates computed as moving average over last 5 years fron ONS data for output per worker for the whole economy.

Figure 3: The decline in productivity growth is an international phenomonon. Data obtained from Extended Penn World Tables. Note that this data only goes up to the start of the 2008 recession.

Throughout the capitalist world this law is in effect, slowing down the growth of labour productivity. The capitalist class seek cheap labour, which systematically holds back technical progress. They show chronic unwillingness to invest. Orthodox economists call this secular stagnation .

You can see the effect clearly in the decline in the improvement in labour productivity shown in Figs 2,3.

Immediate measures

- The inability of 20th century socialism to progress to communism led to the crisis of the USSR.

- Communism requires a definite stage of development of technology.

- This stage was only reached at the very end of the 20th century.

- But this problem of technical adequacy can not be understood in just humanist terms of ‘plenty’ or in terms of ‘the realm of necessity’.

1 What is a mode of production

Is Socialism a mode of production?The standard account, derived from Stalin, is that a mode of production is a combination of productive forces and production relations:

Mode of production = productive forces + production relations

This was sumarised by Stalin as

the productive forces are only one aspect of production, only one aspect of the mode of production, an aspect that expresses the relation of men to the objects and forces of nature which they make use of for the production of material values. Another aspect of production, another aspect of the mode of production, is the relation of men to each other in the process of production, men’s relations of production. [19]

This has been the orthodoxy, but I think it is wrong. Another meaning of the phrase mode of production is, according to Marx, the mode of material production. This mode of production, according to Marx’s 1857 preface, conditions the social and political life. The relations of production only have to be appropriate to the productive forces.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life.[12]

This conception had been expressed by Marx ten years earlier in his pithy phrase :

The hand mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam mill, society with the industrial capitalist. [11]

In this conception the essential feature of capitalist production is that it is machine industry, production by means of (steam) powered machines. But this should give us pause to think, for is not socialism also characterised by machine production, by the use of artificial forms of energy?Recall that Lenin expressed this very idea when he gave the following equation:

Socialism = Soviet power + Electrification

Since the difference between steam power and electrical power is secondary, and we know that capitalist economies also use electricity, the important point is that capitalism and socialism share the same mode of production.

We can summarize this in two equations defining the mode of production:

Capitalist mode of production = powered machine industry.

Socialist mode of production = electric machine industry.

So the socialist mode of production is a subset of the machine mode of production – that which uses nationwide electric grids. Hence the first aim of the USSR was to set up GOLERO the electricity plan.

Socialism and capitalism differ not so much in mode of production as in the social relations.

Capitalist production relations =

Commodity production +

Private ownership +

Wage labour+

Market anarchy

Private ownership +

Wage labour+

Market anarchy

Socialist production relations =

Commodity form of consumer goods+

Public ownership +

Wage labour +

Planning

The significant differences are firstly that socialist production relations can restrict the commodity form to the consumer goods market. Within the publicly owned sector there is no change in ownership as means of production go from one state factory to another – hence these goods are not commodities. Secondly the socialist economy substitutes public for private ownership. Third it replaces the anarchic market with directive planning. These are differences in production relations but not in the mode of production.Public ownership +

Wage labour +

Planning

2 Marx vs USSR on Communism

Marx, in Critique of the Gotha Programme presents a three stage process of transition to communism.- Capitalism

- First stage communism No commodities or money, no private owners, payment in labour tokens according to physical work done. Public services paid for by an income tax on labour incomes.

- Second stage communism Payment according to need, large families etc get higher incomes.

Now let me contrast this scheme with what became the Soviet orthodoxy derived variously from the Bukharin text mentioned earlier and from Stalin[18]. Again we have a 3 stage model

- Capitalism

- Socialism: Commodities and money are kept, state+coop ownership, payment in money wages according to work done and status of work ( male jobs paid more than female ), indirect taxes on sales not income tax provide the main state revenue.

- Communism: Commodity production replaced by barter, free distribution of many goods, full state ownership.

3 Why did USSR not reach communism?

The material and technical basis of communism will be built up by the end of the second decade (1971-80), ensuring an abundance of material and cultural values for the whole population ; Soviet society will come close to a stage where it can introduce the principle of distribution according to needs, and there will be a gradual transition to one form of ownership-public ownership . Thus, a communist society will in the main be built in the U.S.S.R . The construction of communist society will be fully completed in the subsequent period. (Programme CPSU 1960)

The USSR in 1960 was still very ambitious. They had a very optimistic time table for overtaking US and in many key industries this goal was in fact achieved. The transition to communism was seen solely in terms of quantity of output not in terms of changed social relations. A key technical development was still seen to be electrification: Electrification, which is the pivot of the economic construction of communist society,plays a key role in the development of all economic branches and in the effecting of all modern technological progress. It is therefore important to ensure the priority development of electric power output. It is notable that no particular attention was paid to information technology as an enabling technology for communism.How well did they actually do? Well table 1 shows that in their key goal of electricity the USSR was already by 1990 doing better than the leading European capitalist countries had achieve a quarter century later.

Table 1: Comparison of power available to different economies converted into human labour effort equivalents per head of population. Assumption is that a manual worker could do 216 KWh per year of work.

| year | Gwh | human labour | |

| equiv per head | |||

| China | 2014 | 5665000 | 19.2 |

| US | 2014 | 4331000 | 63.1 |

| EU | 2014 | 3166000 | 19.7 |

| USSR | 1990 | 1728000 | 27.3 |

| USSR | 1940 | 48000 | 1.2 |

| USSR | 1931 | 8800 | 0.3 |

| Russia | 1913 | 1300 | 0.0 |

| GB | 2014 | 338000 | 24.8 |

| GB | 1907 | 61320 | 7.3 |

What about food production?

How well did the USSR achieve its goals there?

Pretty well according to Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of late Soviet with UK, Brazil and US annual per capita output of major protein foods. Note that for all categories the late USSR had better figures. Sources [14], FAOSTAT and USDA databases.

| Year | Meat | Milk | Eggs | |

| Kg | Kg | Units | ||

| USSR | 1988 | 69 | 375 | 299 |

| Brazil | 1988 | 49 | 96 | 163 |

| UK | 1988 | 55 | 265 | 201 |

| USA | 1988 | 58 | ||

| USA | 1990 | 236 | ||

| USA | 1995 | 259 |

But Soviet growth slowed down. The Kruschev era had assumed continued exponential growth and had defined communism in terms of achieving exponential growth. The assumption of exponential growth was unrealistic. Actual growth can not be exponential for long, it inevitably starts to slow down. Actual growth tends to follow a logistic curve like this.

c

Khrushchev s Communism downplayed social change

Under communism there will be no classes, and the socio-economic and cultural distinctions, and differences in living conditions, between town and countryside will disappear ; the countryside will rise to the level of the town in the development of the productive forces and the nature of work, the forms of production relations, living conditions and the well-being of the population. (Programme CPSU 1960)But the concrete programme gave no measures to abolish classes or abolish money and commodities. When the impossibility of continued 10% growth made itself felt, this was seen as the failure of communism, since social change had not been at its core. If society was not moving forward, it failed to morally inspire people and by the late 1980s communists could not resist the pressures from capitalist ideology.

4 Bourgeois theorists said Communism impossible

Von-Mises

Only money provides a rational basis for comparing costs Calculation in terms of labour time impractical because of the millions of equations that would need to be solved.Hayek

Market is like a telephone system exchanging information to tie up economy Only the market can solve problem of dispersed informationThere was some limited truth in this. Marx s communism was not yet possible in 1960 due to limitations in information processing. Marx s Communism stage 1 assumed

- No money

- Calculation in terms of labour time and use values

- Payment in labour credits

Money was still needed for economic calculation even in the planned sector. There was a problem of aggregation in planning which required setting monetary objectives. There was an inability to handle disaggregated plans at all Union level. Money was still needed for wage payments. But cash led to black markets, corruption and pressure to restore capitalist relations.

5 Key developments in productive forces since 1960

But since 1960 there have been a set of technical advances that allow us to remove these old objections to communist economics.Internet

which allows real-time cybernetic planning and can solve the problem of dispersed information – Hayeks key objection

Big-data

allows concentration of the information needed for planning.

Super-computers

can solve the millions of equations in seconds – von Mises objection

Electronic payment cards

allow replacement of cash with non transferable labour credits.

Computational complexity

How easy is it to solve the millions of equations. There are some problems that become computationally intractable even for the largest computers. Is economic planning or the use of labour accounting like that?No it is not. In a series of papers[2,6,5,4,9,8], Allin Cottrell, Greg Michaelson and I have shown that the computational complexity of computing labour values for an entire economy with N distinct products grows as Nlog(N) This means that it is highly tractable and easily solved by modern computers

Direct Democracy

It is also possible to harness computer networks and mobile phone voting to allow direct democratic control by the mass of the population over the economy. This allows major strategic decisions taken democratically, questions like: How much labour to devote to education? How much to health, pensions, sick? How much to environmental protection? How much to national defence? How much to new investment?All this can be done by direct voting using computers or mobile phones every year. We have prototyped software to aggregate the wishes of the public this way[7,15,16,3].

Equivalence

Marx s principle was that non-public goods should be distributed on the equivalence principle – you get back in goods the same amount of labour – after tax – that you perform. Hence goods are priced in labour hours. Cybernetic feedback from sales to the plan adjusts output to consumer needs as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cybernetic planning

Marx argued that calculation in terms of labour time would lead to greater efficiency. The wages system undervalues the real social cost of labour and deters the use of the most modern machinery. Transition to communist calculation will lead to the rational use of labour time, and faster growth of labour productivity.

Figure 2: The growth of labour productivity has been shrinking over the last half century in the UK. Growth rates computed as moving average over last 5 years fron ONS data for output per worker for the whole economy.

Figure 3: The decline in productivity growth is an international phenomonon. Data obtained from Extended Penn World Tables. Note that this data only goes up to the start of the 2008 recession.

Throughout the capitalist world this law is in effect, slowing down the growth of labour productivity. The capitalist class seek cheap labour, which systematically holds back technical progress. They show chronic unwillingness to invest. Orthodox economists call this secular stagnation .

You can see the effect clearly in the decline in the improvement in labour productivity shown in Figs 2,3.

6 Transition steps to first stage of communism

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.

Of course, in the beginning, this cannot be effected except by means of despotic inroads on the rights of property, and on the conditions of bourgeois production; by means of measures, therefore, which appear economically insufficient and untenable, but which, in the course of the movement, outstrip themselves, necessitate further inroads upon the old social order, and are unavoidable as a means of entirely revolutionising the mode of production.

These measures will, of course, be different in different countries.[13]

Nevertheless, in most socialist countries, the following communist measures will be pretty generally applicable.Of course, in the beginning, this cannot be effected except by means of despotic inroads on the rights of property, and on the conditions of bourgeois production; by means of measures, therefore, which appear economically insufficient and untenable, but which, in the course of the movement, outstrip themselves, necessitate further inroads upon the old social order, and are unavoidable as a means of entirely revolutionising the mode of production.

These measures will, of course, be different in different countries.[13]

Immediate measures

- Monetary unit converted to the labour hour set at the average value created per hour.

- Move from state funding from profits of state enterprises to state entirely funded by progressive income tax.

- Legislation to give employees right -before tax to full value created in enterprise

- Conversion of remaining private firms to cooperatives

- Develop centralised internet system to track all purchases and sales.

- Withdraw all paper money and coins, replace with electronic cards

- Private circulation of money eliminated, and money only used by consumers to purchase final goods from public stores.

- Commodity exchange between enterprises replaced by computerised directive planning

- Equalisation of pay rates between men and women and between different professions and trades

References

[1] Nikola Bukharin. ABC of Communism.

[2] Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell. Labour value and socialist economic calculation. Economy and Society, 18(1):71-99, 1989.

[3] Paul Cockshott and Karen Renaud. Extending handivote to handle digital economic decisions. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM-BCS Visions of Computer Science Conference, page 5. British Computer Society, 2010.

[4] W Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell. Economic planning, computers and labor values. conference Karl Marx and the Challenges of the 21st Century, Havana, Cuba, May, pages 5-8, 1999.

[5] W Paul Cockshott and Allin F Cottrell. Information and economics: a critique of Hayek. Research in Political Economy, 16:177-202, 1997.

[6] W Paul Cockshott and Allin F Cottrell. Value, markets and socialism. Science & Society, pages 330-357, 1997.

[7] WP Cockshott and K. Renaud. HandiVote: simple, anonymous, and auditable electronic voting. Journal of information Technology and Politics, 6(1):60-80, 2009.

[8] Allin Cottrell, Paul Cockshott, and Greg Michaelson. Is economic planning hypercomputational? The argument from Cantor diagonalisation. School of Mathematical and Computer Sciences (MACS), Heriot-Watt University Edinburgh, available at: www. macs. hw. ac. uk/ greg/publications/ccm. IJUC07. pdf (accessed December 10, 2008), 2007.

[9] Allin Cottrell, WP Cockshott, and Greg Michaelson. Cantor diagononlalisation and planning. Journal of Unconventional Computing, 5(3-4):223-236, 2009.

[10] Karl Kautsky. The social revolution. CH Kerr, 1902.

[11] Karl Marx. Poverty of philosophy. 1847.

[12] Karl Marx. Preface and Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Foreign Languages Press, 1976.

[13] Karl Marx and Friederick Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. S. Moore. Moscow: Progress.(First published 1848.), 1977.

[14] Bertram Patrick Pockney. Soviet statistics since 1950. Aldershot (UK) Dartmouth, 1991.

[15] Karen Renaud and WP Cockshott. Electronic plebiscites. 2007.

[16] KV Renaud and WP Cockshott. Handivote: Checks, balances and threat analysis. Submitted for Review, 2009.

[17] M. Salvadori. Karl Kautsky and the socialist revolution, 1880-1938. Verso Books, 1990.

[18] Joseph Stalin. Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR. Moscow, 1952.

[19] Josif Vissarionovic Stalin. Dialectical and historical materialism. Lawrence & Wishart, 1943.

[2] Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell. Labour value and socialist economic calculation. Economy and Society, 18(1):71-99, 1989.

[3] Paul Cockshott and Karen Renaud. Extending handivote to handle digital economic decisions. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM-BCS Visions of Computer Science Conference, page 5. British Computer Society, 2010.

[4] W Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell. Economic planning, computers and labor values. conference Karl Marx and the Challenges of the 21st Century, Havana, Cuba, May, pages 5-8, 1999.

[5] W Paul Cockshott and Allin F Cottrell. Information and economics: a critique of Hayek. Research in Political Economy, 16:177-202, 1997.

[6] W Paul Cockshott and Allin F Cottrell. Value, markets and socialism. Science & Society, pages 330-357, 1997.

[7] WP Cockshott and K. Renaud. HandiVote: simple, anonymous, and auditable electronic voting. Journal of information Technology and Politics, 6(1):60-80, 2009.

[8] Allin Cottrell, Paul Cockshott, and Greg Michaelson. Is economic planning hypercomputational? The argument from Cantor diagonalisation. School of Mathematical and Computer Sciences (MACS), Heriot-Watt University Edinburgh, available at: www. macs. hw. ac. uk/ greg/publications/ccm. IJUC07. pdf (accessed December 10, 2008), 2007.

[9] Allin Cottrell, WP Cockshott, and Greg Michaelson. Cantor diagononlalisation and planning. Journal of Unconventional Computing, 5(3-4):223-236, 2009.

[10] Karl Kautsky. The social revolution. CH Kerr, 1902.

[11] Karl Marx. Poverty of philosophy. 1847.

[12] Karl Marx. Preface and Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Foreign Languages Press, 1976.

[13] Karl Marx and Friederick Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. S. Moore. Moscow: Progress.(First published 1848.), 1977.

[14] Bertram Patrick Pockney. Soviet statistics since 1950. Aldershot (UK) Dartmouth, 1991.

[15] Karen Renaud and WP Cockshott. Electronic plebiscites. 2007.

[16] KV Renaud and WP Cockshott. Handivote: Checks, balances and threat analysis. Submitted for Review, 2009.

[17] M. Salvadori. Karl Kautsky and the socialist revolution, 1880-1938. Verso Books, 1990.

[18] Joseph Stalin. Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR. Moscow, 1952.

[19] Josif Vissarionovic Stalin. Dialectical and historical materialism. Lawrence & Wishart, 1943.