From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedi

| John Law | |

|---|---|

John Law, by Casimir Balthazar | |

| Born | 1671 Edinburgh Scotland |

| Died | 21 March 1729 (aged 57) Venice Republic of Venice |

| Occupation | Economist, Banker, Financier, Author, Controller-General of Finances. |

| Signature |  |

In 1716 Law established the Banque Générale in France, a private bank, but three-quarters of the capital consisted of government bills and government-accepted notes, effectively making it the first central bank of the nation. He was responsible for the Mississippi Bubble and a chaotic economic collapse in France.

Law was a gambler and a brilliant mental calculator. He was known to win card games by mentally calculating the odds. He originated economic ideas such as "The Scarcity Theory of Value" and the "Real bills doctrine". Law’s views held that money creation will stimulate the economy, that paper money is preferable to metallic money which should be banned, and that shares are a superior form of money since they pay dividends.[1]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Biography

Law was born into a family of bankers and goldsmiths from Fife; his father had purchased a landed estate at Cramond on the Firth of Forth and was known as Law of Lauriston. Law joined the family business at age fourteen and studied the banking business until his father died in 1688. Law subsequently neglected the firm in favour of more extravagant pursuits and travelled to London, where he lost large sums of money in gambling.[2]On 9 April 1694, John Law fought a duel with Edward Wilson in Bloomsbury Square in London.[3] Wilson had challenged Law over the affections of Elizabeth Villiers. Law killed Wilson with a single pass and thrust of his sword.[4] He was arrested, charged with murder and stood trial at the Old Bailey.[4] He appeared before the infamously sadistic 'hanging-judge', Salathiel Lovell and was found guilty of murder, and sentenced to death.[5] He was initially incarcerated in Newgate Prison to await execution.[6] His sentence was later commuted to a fine, upon the ground that the offence only amounted to manslaughter. Wilson's brother appealed and had Law imprisoned, but he managed to escape to Amsterdam.[2]

Law urged the establishment of a national bank to create and increase instruments of credit and the issue of banknotes backed by land, gold, or silver. The first manifestation of Law's system came when he had returned to Scotland and contributed to the debates leading to the Treaty of Union 1707. He published a text entitled Money and Trade Consider'd with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money (1705).[7] Law's propositions of creating a national bank in Scotland were ultimately rejected, and he left to pursue his ambitions abroad.[8]

He spent ten years moving between France and the Netherlands, dealing in financial speculations. Problems with the French economy presented the opportunity to put his system into practice.

He had the idea of abolishing minor monopolies and private farming of taxes. He would create a bank for national finance and a state company for commerce, ultimately to exclude all private revenue. This would create a huge monopoly of finance and trade run by the state, and its profits would pay off the national debt. The council called to consider Law's proposal, including financiars such as Samuel Bernard, rejected the proposition on 24 October 1715.[9]

The wars waged by Louis XIV left the country completely wasted, both economically and financially. The resultant shortage of precious metals led to a shortage of coins in circulation, which in turn limited the production of new coins. It was in this context that the regent, Philippe d'Orléans, appointed John Law as Controller General of Finances.

As Controller General, Law instituted many beneficial reforms (some of which had lasting effect, others of which were soon abolished). He tried to break up large land-holdings to benefit the peasants; he abolished internal road and canal tolls; he encouraged the building of new roads, the starting of new industries (even importing artisans but mostly by offering low-interest loans), and the revival of overseas commerce—and indeed industry increased 60% in two years, and the number of French ships engaged in export went from sixteen to three hundred.[10]

Since, following the devastating War of the Spanish Succession, France's economy was stagnant and her national debt was crippling, Law proposed to stimulate industry by replacing gold with paper credit and then increasing the supply of credit, and to reduce the national debt by replacing it with shares in economic ventures.[11] Though they failed, his theories ironically live on 300 years later and "captured many key conceptual points which are very much a part of modern monetary theorizing".[12]

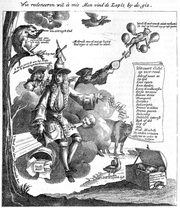

Contemporary political cartoon of Law from Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid (1720); text reads "Law loquitur. The wind is my treasure, cushion, and foundation. Master of the wind, I am master of life, and my wind monopoly becomes straightway the object of idolatry. Less rapidly turn the sails of the windmill on my head than the price of shares in my foolish enterprises."

[edit] Mississippi Company

Law would become the architect of what would later be known as "The Mississippi Bubble"; an event that would begin with the consolidation of the trading companies of Louisiana into a single monopoly (The Mississippi Company), and ended with the collapse of the Banque Generale and subsequent devaluing of The Mississippi Company's shares.[13] The company's shares were ultimately rendered worthless, and initially inflated speculation about their worth led to widespread financial stress, which saw Law dismissed from his post as Chief Director of the Banque Generale end of 1720. Law ultimately fled the country disguised as a woman for his own safety.[13][edit] Later years

Law initially moved to Brussels in impoverished circumstances. He spent the next few years gambling in Rome, Copenhagen and Venice but never regained his former prosperity. Law realised he would never return to France when Orléans died suddenly in 1723 and Law was granted permission to return to London, having received a pardon in 1719. He lived in London for four years and then moved to Venice where he contracted pneumonia and died a poor man in 1729.[edit] Books

- John Law: Economic Theorist and Policy-Maker by Antoin E. Murphy (Oxford University Press, 1997) is the most extensive account of Law's writings. It is given credit for completing the transformation of opinion about Law from a con man (see Mackay below) to an important economic theorist and successful financial leader.

- Letters to John Law by Gavin John Adams (Newton Page, 2012) is a collection of early eighteenth-century political propagandist pamphlets documenting the hysteria surrounding John Law's return to Britain after the collapse of his Mississippi Scheme and expulsion from France. It also contains a very useful chronology and extensive biographical introduction to John Law and the Mississippi Scheme (ISBN 9781934619087).

- Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson (2000). (ISBN 0-684-87295-1) is a straightforward biography.

- The Poker Face of Wall Street by Aaron Brown (John Wiley & Sons, 2006) credits Law for the inspiration of the modern futures exchange and also the game of Poker.

- John Law – The History of an Honest Adventurer by H. Montgomery Hyde (W. H. Allen, 1969) is one of the earliest favorable accounts of Law's ideas.

- John Law, the father of paper money by Robert Minton (Association Press, 1975) treats Law's financial innovations that led to modern paper money.

- Crime, Cash, Credit and Chaos by Colin McCall (Solcol, 2007) examines the events and circumstances that became Law's dramatic and tragic life.

- Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay, published 1841, contains a colorful negative account of Law's financial activities in France. Available as a reprint and online, including as a free Kindle text.

- The Gamester by Rafael Sabatini (Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, 1949) is a sympathetic fictionalized account of Law's career as financial adviser to the Duke of Orléans, Regent under Louis XV.

[edit] Films

Richard Condie's 1978 National Film Board of Canada (NFB) animated short John Law and the Mississippi Bubble is a humorous interpretation. The film was a collaboration between Condie and his sister, Sharon Condie, who had been inspired to make a film on the Mississippi Bubble after reading Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. The film was produced by the NFB at its newly opened Winnipeg studio. It opened in Canadian cinemas starting in September 1979 and was sold to international broadcasters. The film received an award at the Tampere Film Festival.[14][edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, The Life and Times of Nicolas Dutot, November 2009

- ^ a b Mackay, Charles (1848). ["http://www.econlib.org/library/Mackay/macEx1.html" "1.3"]. Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. London: Office of the National Illustrated Library. "http://www.econlib.org/library/Mackay/macEx1.html".

- ^ Adams, Gavin John (2012). Letters to John Law. Newton Page. pp. xiv, xxi. http://books.google.com/books?id=espxkAw-5bsC&pg=PR21&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ a b Adams, Gavin John (2012). Letters to John Law. Newton Page. p. xxi. http://books.google.com/books?id=espxkAw-5bsC&pg=PR21&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Adams, Gavin John (2012). Letters to John Law. Newton Page. pp. xiv, liii. http://books.google.com/books?id=espxkAw-5bsC&pg=PR14&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Adams, Gavin John (2012). Letters to John Law. Newton Page. p. xxi. http://books.google.com/books?id=espxkAw-5bsC&pg=PR21&dq=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Buchan, James (1997). Frozen Desire: An inquiry into the meaning of money. Picador. pp. 136. ISBN 0-330-35527-9.

- ^ Collier's Encyclopedia (Book 14): "Law, John", page 384. P.F. Collier Inc, 1978.

- ^ Buchan, James (1997). Frozen Desire: An inquiry into the meaning of money. Picador. pp. 141. ISBN 0-330-35527-9.

- ^ Will and Ariel Durant, The Age of Voltaire, Simon & Schuster(1965), page 13

- ^ John Law by Antoin E Murphy, Oxford U. Press, 1997, page 105. http://books.google.com/books?id=0kduEtlToecC&pg=PA105&lpg=PP1&ie=ISO-8859-1&output=html.

- ^ John Law by Antoin E Murphy, Oxford U. Press, 1997, page 1. http://books.google.com/books?id=0kduEtlToecC&pg=PA1&lpg=PP1&ie=ISO-8859-1&output=html.

- ^ a b http://www.yourdictionary.com/finance/the-mississippi-bubble

- ^ Ohayon, Albert. "John Law and the Mississippi Bubble: The Madness of Crowds". NFB.ca Blog. National Film Board of Canada. http://blog.nfb.ca/2011/06/22/john-law-and-the-mississippi-bubble-the-madness-of-crowds/. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: John Law |

- John Law

- Project Gutenberg Edition of Fiat Money Inflation in France: How ...

- John Law: Proto-Keynesian, by Murray Rothbard

Texts on Wikisource:

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Law, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Law, John". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co. 1914.

| |||||

|

Categories:

- Scottish bankers

- Scottish economists

- Physiocrats

- Economy of France

- History of banking

- People from Fife

- Scottish statisticians

- Scottish gamblers

- Duellists

- 1671 births

- 1729 deaths

- Recipients of British royal pardons

- 18th-century Scottish people

- 17th-century Scottish people

- People of the Regency of Philippe d'Orléans

- People of the Ancien Régime

- Deaths from pneumonia

- French Ministers of Finance