The

history of economic thought deals with different thinkers and theories in the subject that became

political economy and

economics from the

ancient world to the present day.

[citation needed] It encompasses many disparate

schools of economic thought. Greek writers such as the philosopher

Aristotle examined ideas about the art of wealth acquisition and questioned whether property is best left in private or public hands.

[citation needed] In medieval times,

scholars such as

Thomas Aquinas argued that it was a

moral obligation of businesses to sell goods at a

just price.

[citation needed]

Scottish

philosopher Adam Smith is often cited as the father of modern economics for his

treatise The Wealth of Nations (1776).

[1][2] His ideas built upon a considerable body of work from predecessors in the eighteenth century particularly the

Physiocrats. His book appeared on the eve of the

Industrial Revolution with associated major changes in the

economy.

[3]

Smith's successors included such

classical economists as the

Rev. Thomas Malthus,

Jean-Baptiste Say,

David Ricardo, and

John Stuart Mill.

[citation needed] They examined ways the landed, capitalist and labouring classes produced and distributed national output and

modeled the effects of

population and

international trade.

[citation needed] In London,

Karl Marx castigated the capitalist system, which he described as exploitative and alienating.

[citation needed] From about 1870,

neoclassical economics attempted to erect a positive, mathematical and scientifically grounded field above normative politics.

[citation needed]

After the wars of the early twentieth century,

John Maynard Keynes led a reaction against what has been described as

governmental abstention from economic affairs, advocating interventionist fiscal policy to stimulate economic demand and growth.

[citation needed] With a world divided between the

capitalist first world, the

communist second world, and the poor of the

third world, the

post-war consensus broke down.

[citation needed] Others like

Milton Friedman and

Friedrich von Hayek warned of

The Road to Serfdom and

socialism, focusing their theories on what could be achieved through better

monetary policy and deregulation.

[citation needed]

As

Keynesian policies seemed to falter in the 1970s there emerged the so-called

New Classical school, with prominent theorists such as

Robert Lucas and

Edward Prescott.

[citation needed] Governmental economic policies from the 1980s were challenged, and

development economists like

Amartya Sen and

information economists like

Joseph Stiglitz introduced new ideas to economic thought in the twenty-first century.

[citation needed]

[edit] Early economic thought

The earliest discussions of economics date back to ancient times (e.g.

Chanakya's

Arthashastra or

Xenophon's

Oeconomicus). Back then, and until the industrial revolution, economics was not a separate discipline but part of philosophy. In

Ancient Athens, a slave based society but also one developing an embryonic model of democracy,

[4] Plato's book

The Republic contained references to specialization of labour and production. But it was his pupil Aristotle that made some of the most familiar arguments, still in economic discourse today.

[edit] Aristotle

Aristotle's

Politics (c.a. 350 BC) was mainly concerned to analyse different forms of a state (

monarchy,

aristocracy,

constitutional government,

tyranny,

oligarchy,

democracy) as a critique of Plato's advocacy of a ruling class of "philosopher-kings". In particular for economists, Plato had drawn a blueprint of society on the basis of common ownership of resources. Aristotle viewed this model as an oligarchical

anathema. In

Politics, Book II, Part V, he argued that,

Property should be in a certain sense common, but, as a general rule, private; for, when everyone has a distinct interest, men will not complain of one another, and they will make more progress, because every one will be attending to his own business... And further, there is the greatest pleasure in doing a kindness or service to friends or guests or companions, which can only be rendered when a man has private property. These advantages are lost by excessive unification of the state.

[5]

Though Aristotle certainly advocated there be many things held in common, he argued that not everything could be, simply because of the "wickedness of human nature".

[5] "It is clearly better that property should be private", wrote Aristotle, "but the use of it common; and the special business of the legislator is to create in men this benevolent disposition." In

Politics Book I, Aristotle discusses the general nature of households and market exchanges. For him there is a certain "art of acquisition" or "wealth-getting". Money itself has the sole purpose of being a medium of exchange, which means on its own "it is worthless... not useful as a means to any of the necessities of life".

[6]

Nevertheless, points out Aristotle, because the "instrument" of money is the same many people are obsessed with the simple accumulation of money. "Wealth-getting" for one's household is "necessary and honourable", while exchange on the retail trade for simple accumulation is "justly censured, for it is dishonourable".

[7] Of the people he stated they as a whole thought acquisition of wealth (chrematistike) as being either the same as, or a principle of oikonomia (

household management - oikonomos),

[8][9] with

oikos as house and

nomos in fact translated as custom or law.

[9] Aristotle himself was highly disapproving of

usury and cast scorn on making money through means of a

monopoly.

[10]

[edit] Middle Ages

St

Thomas Aquinas taught that raising prices in response to high demand was a type of theft.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) was an Italian theologian and writer on economic issues. He taught in both

Cologne and Paris, and was part of a group of Catholic scholars known as the

Schoolmen, who moved their enquiries beyond theology to philosophical and scientific debates. In the treatise

Summa Theologica Aquinas dealt with the concept of a

just price, which he considered necessary for the reproduction of the social order. Bearing many similarities with the modern concept of long run equilibrium a just price was supposed to be one just sufficient to cover the

costs of production, including the maintenance of a worker and his family. He argued it was immoral for sellers to raise their prices simply because buyers were in pressing need for a product.

Aquinas discusses a number of topics in the format of questions and replies, substantial tracts dealing with Aristotle's theory. Questions 77 and 78 concern economic issues, mainly relate to what a

just price is, and to the fairness of a seller dispensing faulty goods. Aquinas argued against any form of cheating and recommended compensation always be paid in lieu of good service. Whilst human laws might not impose sanctions for unfair dealing,

divine law did, in his opinion. One of Aquinas' main critics

[11] was

Duns Scotus (1265–1308) in his work

Sententiae (1295).

Originally from

Duns Scotland, he taught in Oxford, Cologne and Paris. Scotus thought it possible to be more precise than Aquinas in calculating a just price, emphasising the costs of labour and expenses – though he recognised that the latter might be inflated by exaggeration, because buyer and seller usually have different ideas of what a just price comprises. If people did not benefit from a transaction, in Scotus' view, they would not trade. Scotus defended merchants as performing a necessary and useful social role, transporting goods and making them available to the public.

[11]

[edit] Mercantilists and nationalism

Main article:

Mercantilism

A 1638 painting of a French seaport during the heyday of

mercantilism.

From the

localism of the Middle Ages, the waning

feudal lords, new national economic frameworks began to be strengthened. From 1492 and explorations like

Christopher Columbus' voyages, new opportunities for trade with the

New World and Asia were opening. New powerful monarchies wanted a powerful state to boost their status. Mercantilism was a political movement and an economic theory that advocated the use of the state's

military power to ensure local markets and supply sources were

protected.

Mercantile theorists thought

international trade could not benefit all countries at the same time. Because money and

gold were the only source of riches, there was a limited quantity of resources to be shared between countries. Therefore,

tariffs could be used to encourage exports (meaning more money comes into the country) and discourage imports (sending wealth abroad). In other words a positive

balance of trade ought to be maintained, with a surplus of exports. The term mercantilism was not in fact coined until the late 1763 by

Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau and popularised by

Adam Smith, who vigorously opposed its ideas.

[edit] Thomas Mun

English businessman Thomas Mun (1571–1641) represents early mercantile policy in his book

England's Treasure by Foraign Trade . Although it was not published until 1664 it was widely circulated as a manuscript before then. He was a member of the

East India Company and also wrote about his experiences there in

A Discourse of Trade from England unto the East Indies (1621).

According to Mun, trade was the only way to increase England's treasure (i.e., national wealth) and in pursuit of this end he suggested several courses of action. Important were frugal consumption to increase the amount of goods available for export, increased utilisation of land and other domestic natural resources to reduce import requirements, lowering of export duties on goods produced domestically from foreign materials, and the export of goods with

inelastic demand because more money could be made from higher prices.

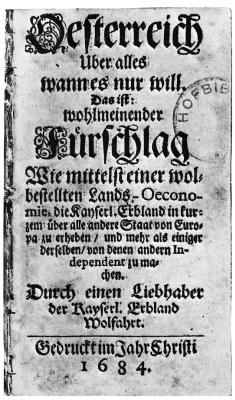

[edit] Philipp von Hörnigk

Philipp von Hörnigk (1640–1712, sometimes spelt

Hornick or

Horneck) was born in

Frankfurt am Main and became an Austrian civil servant writing in a time when his country was constantly threatened by

Ottoman invasion. In

Österreich Über Alles, Wann es Nur Will (1684,

Austria Over All, If She Only Will) he laid out one of the clearest statements of mercantile policy. He listed nine principal rules of national economy.

To inspect the country's soil with the greatest care, and not to leave the

agricultural possibilities of a single corner or clod of earth unconsidered... All commodities found in a country, which cannot be used in their natural state, should be worked up within the country... Attention should be given to the population, that it may be as large as the country can support...

gold and silver once in the country are under no circumstances to be taken out for any purpose... The inhabitants should make every effort to get along with their domestic products... [Foreign commodities] should be obtained not for gold or silver, but in exchange for other domestic wares... and should be imported in unfinished form, and worked up within the country... Opportunities should be sought night and day for selling the country's

superfluous goods to these foreigners in manufactured form... No

importation should be allowed under any circumstances of which there is a sufficient supply of suitable quality at home.

Nationalism, self-sufficiency and national power were the basic policies proposed.

[12]

[edit] Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) was Minister of Finance under King

Louis XIV of France. He set up national

guilds to regulate major industries. Silk, linen, tapestry, furniture manufacture and wine were examples of the crafts in which France specialised, all of which came to require membership of a guild to operate in. These remained until the

French revolution. According to Colbert, "It is simply, and solely, the abundance of money within a state [which] makes the difference in its grandeur and power."

[citation needed]

[edit] British enlightenment

Britain had gone through some of its most troubling times through the 17th century, enduring not only political and religious division in the

English Civil War, King

Charles I's execution and the

Cromwellian dictatorship, but also the

plagues and

fires. The monarchy was restored under

Charles II, who had catholic sympathies, but his successor

King James II was swiftly ousted. Invited in his place were Protestant

William of Orange and

Mary, who assented to the

Bill of Rights 1689 ensuring that the

Parliament was dominant in what became known as the

Glorious revolution. The upheaval had seen a number of huge scientific advances, including

Robert Boyle's discovery of the

gas pressure constant (1660) and Sir

Isaac Newton's publication of

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), which described the three laws of motion and his

law of universal gravitation. All these factors spurred the advancement of economic thought. For instance,

Richard Cantillon (1680–1734) consciously imitated Newton's forces of inertia and gravity in the natural world with human reason and market competition in the economic world.

[13] In his

Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General, he argued rational self-interest in a system of freely adjusting markets would lead to order and mutually compatible prices. Unlike the mercantilist thinkers however, wealth was found not in trade but in human

labour. The first person to tie these ideas into a political framework was

John Locke.

[edit] John Locke

John Locke (1632–1704) was born near Bristol and educated in London and Oxford. He is considered one of the most significant philosophers of his era mainly for his critique of

Thomas Hobbes' defense of absolutism in

Leviathan (1651) and the development of

social contract theory. Locke believed that people contracted into society which was bound to protect their rights of property.

[14] He defined property broadly to include people's lives and liberties, as well as their wealth. When people combined their labour with their surroundings, then that created property rights. In his words from his

Second Treatise on Civil Government (1689),

God hath given the world to men in common... Yet every man has a property in his own person. The labour of his body and the work of his hands we may say are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.

[15]

Locke was arguing that not only should the government cease interference with people's property (or their "lives, liberties and estates") but also that it should positively work to ensure their protection. His views on price and money were laid out in a letter to a

Member of Parliament in 1691 entitled

Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money (1691). Here Locke argued that the "price of any commodity rises or falls, by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers", a rule which "holds universally in all things that are to be bought and sold."

[16]

[edit] Dudley North

Dudley North argued that the results of mercantile policy would be undesirable.

Dudley North (1641–1691) was a wealthy merchant and landowner. He worked as an official for the

Treasury and was opposed to most mercantile policy. In his

Discourses upon trade (1691), which he published anonymously, he argued that the assumption of needing a favourable trade balance was wrong. Trade, he argued, benefits both sides, it promotes

specialisation, the

division of labour and produces an increase in wealth for everyone. Regulation of trade interfered with these benefits by reducing the flow of wealth.

[edit] David Hume

David Hume (1711–1776) agreed with North's philosophy and denounced

mercantile assumptions. His contributions were set down in

Political Discourses (1752), later consolidated in his

Essays, Moral, Political, Literary (1777). Added to the fact that it was undesirable to strive for a favourable

balance of trade it is, said Hume, in any case impossible.

Hume held that any surplus of

exports that might be achieved would be paid for by imports of gold and silver. This would increase the

money supply, causing prices to rise. That in turn would cause a decline in exports until the balance with imports is restored.

[edit] Francis Hutcheson

Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) was teacher to

Adam Smith during 1737-1740,

[17] and is considered to be at the end of a long tradition of thought on economics as "household or family (

οἶκος) management",

[18][19][20] stemming from Xenophon's work

Oeconomicus.

[21][22]

[edit] The circular flow

Main article:

Physiocrats

Similarly disenchanted with regulation on trademarks inspired by mercantilism, a Frenchman name

Vincent de Gournay (1712–1759) is reputed to have asked why it was so hard to

laissez faire, laissez passer (free enterprise, free trade). He was one of the early physiocrats, a word from Greek meaning "government of nature", who held that agriculture was the source of wealth. As historian

David B. Danbom wrote, the Physiocrats "damned cities for their artificiality and praised more natural styles of living. They celebrated farmers."

[23] Over the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century big advances in

natural science and

anatomy were being made, including the discovery of

blood circulation through the human body. This concept was mirrored in the physiocrats' economic theory, with the notion of a

circular flow of income throughout the economy.

François Quesnay (1694–1774) was the court physician to King

Louis XV of France. He believed that trade and industry were not sources of wealth, and instead in his book,

Tableau économique (1758, Economic Table) argued that agricultural surpluses, by flowing through the economy in the form of rent, wages and purchases were the real economic movers. Firstly, said Quesnay, regulation impedes the flow of income throughout all

social classes and therefore economic development. Secondly, taxes on the productive classes, such as

farmers, should be reduced in favour of rises for unproductive classes, such as

landowners, since their luxurious way of life distorts the income flow. David Ricardo later showed that taxes on land are non-transferable to tenants in his

Law of Rent.

Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) was born in Paris and from an old

Norman family. His best known work,

Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses (1766,

Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth) developed Quesnay's theory that

land is the only source of

wealth. Turgot viewed society in terms of three classes: the productive agricultural class, the salaried artisan class (

classe stipendice) and the landowning class (

classe disponible). He argued that only the net product of land should be taxed and advocated the complete freedom of

commerce and

industry.

In August 1774, Turgot was appointed to be Minister of Finance and in the space of two years introduced many anti-mercantile and anti-feudal measures supported by the King. A statement of his guiding principles, given to the King were "no

bankruptcy, no

tax increases, no borrowing." Turgot's ultimate wish was to have a single tax on land and abolish all other indirect taxes, but measures he introduced before that were met with overwhelming opposition from landed interests. Two

edicts in particular, one suppressing

corvées (charges from farmers to aristocrats) and another renouncing privileges given to guilds inflamed influential opinion. He was forced from office in 1776.

[edit] Adam Smith and The Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith (1723–1790) is popularly seen as the father of modern political economy. His publication of the

An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776 happened to coincide not only with the

American Revolution, shortly before the Europe wide upheavals of the

French Revolution, but also the dawn of a new

industrial revolution that allowed more wealth to be created on a larger scale than ever before. Smith was a Scottish moral philosopher, whose first book was

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). He argued in it that people's ethical systems develop through personal relations with other individuals, that right and wrong are sensed through others' reactions to one's behaviour. This gained Smith more popularity than his next work,

The Wealth of Nations, which the general public initially ignored.

[24] Yet Smith's

political economic magnum opus was successful in circles that mattered.

[edit] Context

William Pitt, the

Tory Prime Minister in the late 1780s based his tax proposals on Smith's ideas and advocated

free trade as a devout disciple of

The Wealth of Nations.

[25] Smith was appointed a commissioner of

customs and within twenty years Smith had a following of new generation writers who were intent on building the

science of political economy.

[24]

Smith expressed an affinity himself to the opinions of

Edmund Burke, known widely as a political philosopher, a

Member of Parliament.

Burke is the only man I ever knew who thinks on economic subjects exactly as I do without any previous communication having passed between us.

[26]

Burke was an established political economist himself, with his book

Thoughts and Details on Scarcity. He was widely critical of liberal politics, and condemned the

French Revolution which began in 1789. In

Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) he wrote that the "age of chivalry is dead, that of sophisters, economists and calculators has succeeded, and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever." Smith's contemporary influences included

François Quesnay and

Jacques Turgot whom he met on a stay in Paris, and David Hume, his Scottish compatriot. The times produced a common need among thinkers to explain social upheavals of the

Industrial revolution taking place, and in the seeming chaos without the feudal and monarchical structures of Europe, show there was order still.

[edit] The invisible hand

| "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages."[27] |

| Adam Smith's famous statement on self-interest |

Smith argued for a "

system of natural liberty"

[28] where individual effort was the producer of social good. Smith believed even the selfish within society were kept under restraint and worked for the good of all when acting in a competitive market. Prices are often unrepresentative of the true value of goods and services. Following

John Locke, Smith thought true value of things derived from the amount of labour invested in them.

Every man is rich or poor according to the degree in which he can afford to enjoy the necessaries, conveniencies, and amusements of human life. But after the

division of labour has once thoroughly taken place, it is but a very small part of these with which a man's own labour can supply him. The far greater part of them he must derive from the labour of other people, and he must be rich or poor according to the quantity of that labour which he can command, or which he can afford to purchase. The value of any commodity, therefore, to the person who possesses it, and who means not to use or consume it himself, but to exchange it for other commodities, is equal to the quantity of labour which it enables him to purchase or command. Labour, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities. The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it.

[29]

When the butchers, the brewers and the bakers acted under the restraint of an open market economy, their pursuit of self-interest, thought Smith, paradoxically drives the process to correct real life

prices to their just values. His classic statement on competition goes as follows.

When the quantity of any commodity which is brought to market falls short of the effectual demand, all those who are willing to pay... cannot be supplied with the quantity which they want... Some of them will be willing to give more. A

competition will begin among them, and the market price will rise... When the quantity brought to market exceeds the effectual

demand, it cannot be all sold to those who are willing to pay the whole value of the

rent, wages and

profit, which must be paid to bring it thither... The market price will sink...

[30]

Smith believed that a market produced what he dubbed the "progress of opulence". This involved a chain of concepts, that the

division of labour is the driver of economic efficiency, yet it is limited to the widening process of markets. Both labour division and market widening requires more intensive

accumulation of capital by the entrepreneurs and leaders of business and industry. The whole system is underpinned by maintaining the security of

property rights.

[edit] Limitations

Smith's vision of a free market economy, based on secure property, capital accumulation, widening markets and a division of labour contrasted with the mercantilist tendency to attempt to "regulate all evil human actions."

[28] Smith believed there were precisely three legitimate functions of government. The third function was...

...erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions, which it can never be for the interest of any individual or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain... Every system which endeavours... to draw towards a particular species of industry a greater share of the capital of the society than what would naturally go to it... retards, instead of accelerating, the progress of the society toward real wealth and greatness.

In addition to the necessity of public leadership in certain sectors Smith argued, secondly, that

cartels were undesirable because of their potential to limit production and quality of goods and services.

[31] Thirdly, Smith criticised government support of any kind of

monopoly which always charges the highest price "which can be squeezed out of the buyers".

[32] The existence of

monopoly and the potential for

cartels, which would later form the core of

competition law policy, could distort the benefits of free markets to the advantage of businesses at the expense of

consumer sovereignty.

[edit] Classical political economy

The

classical economists were referred to as a group for the first time by

Karl Marx.

[33] One unifying part of their theories was the

labour theory of value, contrasting to value deriving from a

general equilibrium of supply and demand. These economists had seen the first economic and social transformation brought by the Industrial Revolution: rural depopulation, precariousness, poverty, apparition of a working class.

They wondered about the population growth, because the

demographic transition had begun in Great Britain at that time. They also asked many fundamental questions, about the source of value, the causes of economic growth and the role of money in the economy. They supported a free-market economy, arguing it was a natural system based upon freedom and property. However, these economists were divided and did not make up a unified current of thought.

A notable current within classical economics was

underconsumption theory, as advanced by the

Birmingham School and Malthus in the early 19th century. These argued for government action to mitigate unemployment and economic downturns, and was an intellectual predecessor of what later became

Keynesian economics in the 1930s. Another notable school was

Manchester capitalism, which advocated free trade, against the previous policy of

mercantilism.

[edit] Jeremy Bentham

Main article:

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham believed in "the greatest good for the greatest number".

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) was perhaps the most radical thinker of his time, and developed the concept of

utilitarianism. Bentham was an

atheist, a

prison reformer,

animal rights activist, believer in

universal suffrage,

free speech,

free trade and

health insurance at a time when few dared to argue for any. He was schooled rigorously from an early age, finishing university and being called to the bar at 18. His first book,

A Fragment on Government (1776) published anonymously was a trenchant critique of

William Blackstone's

Commentaries of the laws of England. This gained wide success until it was found that the young Bentham, and not a revered Professor had penned it. In

The Principles of Morals and Legislation (1791) Bentham set out his theory of utility.

[34]

The aim of

legal policy must be to decrease misery and suffering so far as possible while producing the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

[35] Bentham even designed a comprehensive methodology for the calculation of aggregate happiness in society that a particular law produced, a

felicific calculus.

[36] Society, argued Bentham, is nothing more than the total of individuals,

[37] so that if one aims to produce net social good then one need only to ensure that more pleasure is experienced across the board than pain, regardless of numbers.

For example, a law is proposed to make every bus in the city

wheel chair accessible, but slower moving as a result than its

predecessors because of the

new design. Millions of bus users will therefore experience a small amount of displeasure (or "pain") in increased traffic and journey times, but a minority of people using wheel chairs will experience a huge amount of pleasure at being able to catch public transport, which outweighs the aggregate displeasure of other users.

Interpersonal comparisons of utility were allowed by Bentham, the idea that one person's vast pleasure can count more than many others' pain. Much criticism later showed how this could be twisted, for instance, would the

felicific calculus allow a vastly happy dictator to outweigh the dredging misery of his exploited populus? Despite Bentham's methodology there were severe obstacles in measuring people's happiness.

[edit] Jean-Baptiste Say

Say's law, that supply always equals demand, was unchallenged until the 20th century.

Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) was a Frenchman, born in

Lyon who helped to popularise Adam Smith's work in France.

[38] His book,

A Treatise on Political Economy (1803) contained a brief passage, which later became orthodoxy in political economics until the

Great Depression and known as

Say's Law of markets. Say argued that there could never be a general deficiency of demand or a general glut of commodities in the whole economy. People produce things, said Say, to fulfill their own wants, rather than those of others. Production is therefore not a question of supply, but an indication of producers demanding goods.

Say agreed that a part of the income is saved by the households, but in the long term, savings are invested. Investment and consumption are the two elements of demand, so that production

is demand, so it is impossible for production to outrun demand, or for there to be a "general glut" of supply. Say also argued that money was neutral, because its sole role is to facilitate exchanges: therefore, people demand money only to buy commodities. Say said that "money is a veil".

To sum up these two ideas, Say said "products are exchanged for products". At most, there will be different economic sectors whose demands are not fulfilled. But over time supplies will shift, businesses will retool for different production and the market will correct itself. An example of a "general glut" could be unemployment, in other words, too great a supply of workers, and too few jobs. Say's Law advocates would suggest that this necessarily means there is an excess demand for other products that will correct itself. This remained a foundation of economic theory until the 1930s. Say's Law was first put forward by

James Mill (1773–1836) in English, and was advocated by

David Ricardo,

Henry Thornton[39] and

John Stuart Mill. However two political economists, Thomas Malthus and

Sismondi, were unconvinced.

[edit] Thomas Malthus

Malthus cautioned law makers on the effects of poverty reduction policies.

Main article:

Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) was a

Tory minister in the United Kingdom Parliament who, contrasting to Bentham, believed in strict government abstention from social ills.

[40] Malthus devoted the last chapter of his book

Principles of Political Economy (1820) to rebutting Say's law, and argued that the economy could stagnate with a lack of "effectual demand".

[41]

In other words, wages if less than the total costs of production cannot purchase the total output of industry and that this would cause prices to fall. Price falls decrease incentives to invest, and the spiral could continue indefinitely. Malthus is more notorious however for his earlier work,

An Essay on the Principle of Population. This argued that intervention was impossible because of two factors. "Food is necessary to the existence of man", wrote Malthus. "The passion between the sexes is necessary and will remain nearly in its present state", he added, meaning that the "power of the population is infinitely greater than the power in the Earth to produce subsistence for man."

[42]

Nevertheless growth in population is checked by "misery and vice". Any increase in wages for the masses would cause only a temporary growth in population, which given the constraints in the supply of the Earth's produce would lead to misery, vice and a corresponding readjustment to the original population.

[43] However more labour could mean more economic growth, either one of which was able to be produced by an accumulation of capital.

[edit] David Ricardo

Main article:

David Ricardo (1772–1823) was born in London. By the age of 26, he had become a wealthy stock market trader and bought himself a constituency seat in Ireland to gain a platform in the

British parliament's House of Commons.

[44] Ricardo's best known work is his

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, which contains his critique of barriers to international trade and a description of the manner the income is distributed in the population. Ricardo made a distinction between the workers, who received a wage fixed to a level at which they can survive, the landowners, who earn a rent, and capitalists, who own capital and receive a profit, a residual part of the income.

[45]

If population grows, it becomes necessary to cultivate additional land, whose fertility is lower than that of already cultivated fields, because of the law of decreasing productivity. Therefore, the cost of the production of the wheat increases, as well as the price of the wheat: The rents increase also, the wages, indexed to inflation (because they must allow workers to survive) too. Profits decrease, until the capitalists can no longer invest. The economy, Ricardo concluded, is bound to tend towards a

steady state.

To postpone the steady state, Ricardo advocates to promote international trade to import wheat at a low price to fight landowners. The

Corn Laws of the UK had been passed in 1815, setting a fluctuating system of tariffs to stabilise the price of

wheat in the domestic market. Ricardo argued that raising tariffs, despite being intended to benefit the incomes of farmers, would merely produce a rise in the prices of rents that went into the pockets of landowners.

[46]

Furthermore, extra labour would be employed leading to an increase in the cost of wages across the board, and therefore reducing exports and profits coming from overseas business. Economics for Ricardo was all about the relationship between the three "factors of production":

land,

labour and

capital. Ricardo demonstrated mathematically that the

gains from trade could outweigh the perceived advantages of protectionist policy. The idea of

comparative advantage suggests that even if one country is inferior at producing all of its goods than another, it may still benefit from opening its borders since the inflow of goods produced more cheaply than at home, produces a gain for domestic consumers.

[47] According then to Ricardo, this concept would lead to a shift in prices, so that eventually England would be producing goods in which its comparative advantages were the highest.

[edit] John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill, weaned on the philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, wrote the most authoritative economics text of his time.

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was the dominant figure of political economic thought of his time, as well as being a

Member of Parliament for the seat of

Westminster, and a leading political philosopher. Mill was a child prodigy, reading Ancient Greek from the age of 3, and being vigorously schooled by his father

James Mill.

[48] Jeremy Bentham was a close mentor and family friend, and Mill was heavily influenced by

David Ricardo. Mill's textbook, first published in 1848 and titled

Principles of Political Economy was essentially a summary of the economic wisdom of the mid nineteenth century.

[49]

Principles of Political Economy was used as the standard texts by most universities well into the beginning of the twentieth century. On the question of

economic growth Mill tried to find a middle ground between Adam Smith's view of ever expanding opportunities for trade and technological innovation and Thomas Malthus' view of the inherent limits of population. In his fourth book Mill set out a number of possible future outcomes, rather than predicting one in particular. The first followed the Malthusian line that population grew quicker than supplies, leading to falling wages and rising profits.

[50]

The second, per Smith, said if capital accumulated faster than population grew then

real wages would rise. Third, echoing

David Ricardo, should capital accumulate and population increase at the same rate, yet technology stay stable, there would be no change in real wages because supply and demand for labour would be the same. However growing populations would require more land use, increasing food production costs and therefore decreasing profits. The fourth alternative was that technology advanced faster than population and capital stock increased.

[51]

The result would be a prospering economy. Mill felt the third scenario most likely, and he assumed technology advanced would have to end at some point.

[52] But on the prospect of continuing economic growth, Mill was more ambivalent.

I confess I am not charmed with the ideal of life held out by those who think that the normal state of human beings is that of struggling to get on; that the trampling, crushing, elbowing, and treading on each other's heels, which form the existing type of social life, are the most desirable lot of human kind, or anything but the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress.

[53]

Mill is also credited with being the first person to speak of supply and demand as a relationship rather than mere quantities of goods on markets,

[54] the concept of

opportunity cost and the rejection of the

wage fund doctrine.

[55]

[edit] Capitalism and Marx

Just as the term "mercantilism" had been coined and popularised by its critics, like

Adam Smith, so was the term "capitalism" or

Kapitalismus used by its dissidents, primarily

Karl Marx. Karl Marx (1818–1883) was, and in many ways still remains the pre-eminent socialist economist. His combination of political theory represented in the

Communist Manifesto and the

dialectic theory of history inspired by

Friedrich Hegel provided a revolutionary critique of

capitalism as he saw it in the nineteenth century. The

socialist movement that he joined had emerged in response to the conditions of people in the new industrial era and the classical economics which accompanied it. He wrote his magnum opus

Das Kapital at the

British Museum's library.

[edit] Context

Robert Owen (1771–1858) was one industrialist who determined to improve the conditions of his workers. He bought textile mills in

New Lanark,

Scotland where he forbade children under ten to work, set the workday from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. and provided evening schools for children when they finished. Such meagre measures were still substantial improvements and his business remained solvent through higher productivity, though his pay rates were lower than the national average.

[56] He published his vision in

The New View of Society (1816) during the passage of the

Factory Acts, but his attempt from 1824 to begin a new utopian community in

New Harmony, Indiana ended in failure. One of Marx's own influences was the French anarchist/socialist

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. While deeply critical of capitalism and in favour of workers' associations to replace it, he also objected to those contemporary socialists who idolized centralised state-run association. In

System of Economic Contradictions (1846) Proudhon made a wide-ranging critique of capitalism, analysing the contradictory effects of machinery, competition, property, monopoly and other aspects of the economy.

[57][58] Instead of capitalism, he argued for a mutualist system "based upon equality, – in other words, the organisation of labour, which involves the negation of political economy and the end of property." In his book

What is Property? (1840) he argue that property is

theft, a different view than the classical

Mill, who had written that "partial taxation is a mild form of robbery".

[59] However, towards the end of his life, Proudhon modified some of his earlier views. In the posthumously published

Theory of Property, he argued that "property is the only power that can act as a counterweight to the State."

[60] Friedrich Engels, a published radical author, released a book titled

The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844[61] describing people's positions as "the most unconcealed pinnacle of social misery in our day." After Marx died, it was Engels that completed the second volume of

Das Kapital from Marx's notes.

[edit] Das Kapital

The title page of the first edition of

Capital in

German.

Karl Marx begins

Das Kapital with the concept of commodities. Before capitalist societies, says Marx, the mode of production was based on

slavery (e.g. in

ancient Rome) before moving to

feudal serfdom (e.g. in

mediaeval Europe). As society has advanced, economic bondage has become looser, but the current nexus of labour exchange has produced an equally erratic and unstable situation allowing the conditions for

revolution. People buy and sell their labour in the same way as people buy and sell goods and services. People themselves are disposable

commodities. As he wrote in the

Communist Manifesto,

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guildmaster and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another... The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones.

And furthermore from the first page of

Das Kapital,

The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails, presents itself as an immense accumulation of commodities,

[62] its unit being a single commodity. Our investigation must therefore begin with the analysis of a commodity.

Marx's use of the word "commodity" is tied into an extensive

metaphysical discussion of the nature of material wealth, how the objects of wealth are perceived and how they can be used. The concept of a commodity contrasts to objects of the natural world. When people mix their labour with an object it becomes a "commodity". In the natural world there are trees,

diamonds,

iron ore and people. In the economic world they become chairs,

rings,

factories and workers. However, says Marx, commodities have a dual nature, a dual value. He distinguishes the

use value of a thing from its

exchange value, which can be entirely different.

[63] The use value of a thing derives from the amount of labour used to produce it, says Marx, following the classical economists in the

labour theory of value. However, Marx did not believe labour only was the source of use value in things. He believed value can derive too from natural goods and refined his definition of use value to "

socially necessary labour time" (the time people need to produce things when they are not lazy or inefficient).

[64] Furthermore, people subjectively inflate the value of things, for instance because there's a

commodity fetish for glimmering diamonds,

[65] and oppressive power relations involved in commodity production. These two factors mean exchange values differ greatly. An oppressive power relation, says Marx applying the use/exchange distinction to labour itself, in work-wage bargains derives from the fact that employers pay their workers less in "exchange value" than the workers produce in "use value". The difference makes up the capitalist's

profit, or in Marx's terminology, "

surplus value".

[66] Therefore, says Marx, capitalism is a system of

exploitation.

Marx's work turned the

labour theory of value, as the classicists used it, on its head. His dark irony goes deeper by asking what is the socially necessary labour time for the production of labour (i.e. working people) itself. Marx answers that this is the bare minimum for people to subsist and to reproduce with skills necessary in the economy.

[67] People are therefore

alienated from both the fruits of production and the means to realise their potential, psychologically, by their oppressed position in the labour market. But the tale told alongside exploitation and alienation is one of

capital accumulation and

economic growth. Employers are constantly under pressure from market competition to drive their workers harder, and at the limits invest in labour displacing technology (e.g. an assembly line packer for a robot). This raises profits and expands growth, but for the sole benefit of those who have private property in these

means of production. The working classes meanwhile face progressive immiseration, having had the product of their labour exploited from them, having been alienated from the tools of production. And having been fired from their jobs for machines, they end unemployed. Marx believed that a

reserve army of the unemployed would grow and grow, fuelling a downward pressure on wages as desperate people accept work for less. But this would produce a deficit of

demand as the people's

power to purchase products lagged. There would be a glut in unsold products, production would be cut back, profits decline until capital accumulation halts in an

economic depression. When the glut clears, the economy again starts to boom before the next cyclical bust begins. With every

boom and bust, with every capitalist crisis, thought Marx, tension and

conflict between the increasingly polarised classes of capitalists and workers heightens. Moreover smaller firms are being gobbled by larger ones in every business cycle, as power is concentrated in the hands of the few and away from the many. Ultimately, led by the

Communist party, Marx envisaged a revolution and the creation of a classless society. How this may work, Marx never suggested. His primary contribution was not in a blue print for how society would be, but a criticism of what he saw it was.

[edit] After Marx

The first volume of

Das Kapital was the only one Marx alone published. The second and third volumes were done with the help of

Friedrich Engels, and Karl Kautsky, who had become a friend of Engels, saw through the publication of volume four.

Marx had begun a tradition of economists who concentrated equally on political affairs. Also in Germany,

Rosa Luxemburg was a member of the

SPD, who later turned towards the

Communist Party because of their stance against the First World War.

Beatrice Webb in England was a socialist, who helped found both the

London School of Economics (LSE) and the

Fabian Society.

[edit] Neoclassical thought

In the 1860s, a revolution took place in economics. The new ideas were that of the

Marginalist school. Writing simultaneously and independently, a Frenchman (

Léon Walras), an Austrian (

Carl Menger) and an Englishman (

Stanley Jevons) were developing the theory, which had some antecedents. Instead of the price of a good or service reflecting the labor that has produced it, it reflects the marginal usefulness (utility) of the last purchase. This meant that in equilibrium, people's preferences determined prices, including, indirectly the price of labor.

This current of thought was not united, and there were three main schools working independently. The

Lausanne school, whose two main representants were Walras and

Vilfredo Pareto, developed the theories of

general equilibrium and

optimality. The main written work of this school was Walras'

Elements of Pure Economics. The

Cambridge school appeared with Jevons'

Theory of Political Economy in 1871. This English school has developed the theories of the partial equilibrium and has insisted on markets' failures. The main representatives were

Alfred Marshall,

Stanley Jevons and

Arthur Pigou. The

Vienna school was made up of Austrian economists Menger,

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and

Friedrich von Wieser. They developed the theory of capital and has tried to explain the presence of economic crises. It appeared in 1871 with Menger's

Principles of Economics.

[edit] Marginal utility

Carl Menger (1840–1921), an

Austrian economist stated the basic principle of marginal utility in

Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre[68] (1871,

Principles of Economics). Consumers act rationally by seeking to maximise satisfaction of all their preferences. People allocate their spending so that the last unit of a commodity bought creates no more than a last unit bought of something else.

Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) was his English counterpart, and worked as tutor and later professor at

Owens College, Manchester and

University College, London. He emphasised in the

Theory of Political Economy (1871) that at the margin, the satisfaction of goods and services decreases. An example of the

theory of diminishing returns is that for every orange one eats, the less pleasure one gets from the last orange (until one stops eating). Then

Léon Walras (1834–1910), again working independently, generalised marginal theory across the economy in

Elements of Pure Economics (1874). Small changes in people's preferences, for instance shifting from beef to mushrooms, would lead to a mushroom price rise, and beef price fall. This stimulates producers to shift production, increasing mushrooming investment, which would increase market supply and a new price equilibrium between the products – e.g. lowering the price of mushrooms to a level between the two first levels. For many products across the economy the same would go,

if one assumes markets are competitive, people choose on self-interest and no cost in shifting production.

Early attempts to explain away the periodical crises of which Marx had spoken were not initially as successful. After finding a statistical correlation of

sunspots and business fluctuations and following the common belief at the time that sunspots had a direct effect on weather and hence agricultural output, Stanley Jevons wrote,

when we know that there is a cause, the variation of the solar activity, which is just of the nature to affect the produce of agriculture, and which does vary in the same period, it becomes almost certain that the two series of phenomena— credit cycles and solar variations—are connected as effect and cause.

[69]

[edit] Mathematical analysis

Alfred Marshall wrote the main alternative textbook to John Stuart Mill of the day,

Principles of Economics (1882)

Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923) was an Italian economist, best known for developing the concept of an economy that would permit maximizing the utility level of each individual, given the feasible utility level of others from production and exchange. Such a result came to be called "

Pareto efficient". Pareto devised mathematical representations for such a resource allocation, notable in abstracting from institutional arrangements and monetary measures of

wealth or

income distribution.

[70]

Alfred Marshall is also credited with an attempt to put economics on a more mathematical footing. He was the first Professor of Economics at the

University of Cambridge and his work,

Principles of Economics[71] coincided with the transition of the subject from "

political economy" to his favoured term, "

economics". He viewed maths as a way to simplify economic reasoning, though had reservations, revealed in a letter to his student

Arthur Cecil Pigou.

(1) Use mathematics as shorthand language, rather than as an engine of inquiry. (2) Keep to them till you have done. (3) Translate into English. (4) Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life. (5) Burn the mathematics. (6) If you can't succeed in 4, burn 3. This I do often.

[72]

Coming after the marginal revolution, Marshall concentrated on reconciling the classical labour theory of value, which had concentrated on the supply side of the market, with the new marginalist theory that concentrated on the consumer demand side. Marshalls graphical representation is the famous

supply and demand graph, the "Marshallian cross". He insisted it is the intersection of

both supply

and demand that produce an equilibrium of price in a competitive market. Over the long run, argued Marshall, the costs of production and the price of goods and services tend towards the lowest point consistent with continued production.

Arthur Cecil Pigou in

Wealth and Welfare (1920), insisted on the existence of

market failures. Markets are inefficient in case of

economic externalities, and the State must interfere. However, Pigou retained free-market beliefs, and in 1933, in the face of the economic crisis, he explained in

The Theory of Unemployment that the excessive intervention of the state in the labor market was the real cause of massive

unemployment, because the governments had established a minimal wage, which prevented the wages from adjusting automatically. This was to be the focus of attack from Keynes.

[edit] Austrian school

Carl Menger, founder of the Austrian school of economic thought.

[edit] Early Austrian economists

While the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth were dominated increasingly by mathematical analysis, the followers of

Carl Menger, in the tradition of

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, followed a different route, advocating the use of deductive logic instead. This group became known as the Austrian School, reflecting the Austrian origin of many of the early adherents.

Thorstein Veblen in 1900, in his

Preconceptions of Economic Science, contrasted neoclassical

marginalists in the tradition of

Alfred Marshall from the philosophies of the Austrian school.

[73][74]

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (1883–1950) was an Austrian economist and political scientist most known for his works on

business cycles and

innovation. He insisted on the role of the entrepreneurs in an economy. In

Business Cycles: A theoretical, historical and statistical analysis of the Capitalist process(1939), Schumpeter made a synthesis of the theories about business cycles. He suggested that those cycles could explain the economic situations. According to Schumpeter, capitalism necessarily goes through long-term cycles, because it is entirely based upon scientific inventions and innovations. A phase of expansion is made possible by innovations, because they bring

productivity gains and encourage entrepreneurs to invest. However, when investors have no more opportunities to invest, the economy goes into recession, several firms collapse, closures and bankruptcy occur. This phase lasts until new innovations bring a

creative destruction process, i.e. they destroy old products, reduce the employment, but they allow the economy to start a new phase of growth, based upon new products and new

factors of production.

[75]

[edit] Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig von Mises (left) and Friedrich von Hayek (right)

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) was a central figure in the Austrian school. In his treatise on economics,

Human Action, Mises introduced

praxeology, "The science of human action", as a more general conceptual foundation of the social sciences . Praxeology views economics as a series of voluntary trades that increase the satisfaction of the involved parties. Mises also argued that socialism suffers from an unsolvable

economic calculation problem, which according to him, could only be solved through

free market price mechanisms.

[citation needed]

[edit] Friedrich von Hayek

Mises' outspoken

criticisms of socialism had a large influence on the economic thinking of

Friedrich von Hayek (1899–1992), who, while initially sympathetic to socialism, became one of the leading academic critics of

collectivism in the 20th century.

[76] In echoes of Smith's "system of natural liberty", Hayek argued that the market is a "spontaneous order" and actively disparaged the concept of "

social justice".

[77] Hayek believed that all forms of collectivism (even those theoretically based on voluntary cooperation) could only be maintained by a central authority. In his book,

The Road to Serfdom (1944) and in subsequent works, Hayek claimed that socialism required central economic planning and that such planning in turn would lead towards

totalitarianism. Hayek attributed the birth of civilization to

private property in his book

The Fatal Conceit (1988). According to him,

price signals are the only means of enabling each economic decision maker to communicate

tacit knowledge or

dispersed knowledge to each other, to solve the

economic calculation problem. Along with his contemporary

Gunnar Myrdal, Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1974.

[edit] Murray Rothbard

Building on the Austrian School's concept of

spontaneous order, support for a

free market in

money production, and condemnation of

central planning,

Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) advocated abolition of

coercive government control of society and the economy.

[78] He considered the

monopoly force of government the greatest danger to liberty and the long-term well-being of the populace, labeling the

state as "the organization of robbery systematized and writ large" and the locus of the most immoral, grasping and unscrupulous individuals in any society.

[79][80][81][82]

[edit] Depression and reconstruction

Alfred Marshall was still working on his last revisions of his

Principles of Economics at the outbreak of the First World War (1914–1918). The new twentieth century's climate of optimism was soon violently dismembered in the trenches of the Western front, as the civilised world tore itself apart. For four years the production of Britain, Germany and France was geared entirely towards the

war economy's industry of death. In 1917 Russia crumbled into revolution led by

Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik party. They carried Marxist theory as their saviour, and promised a broken country "peace, bread and land" by collectivising the means of production. Also in 1917, the United States of America entered the war on the side of France and Britain, President

Woodrow Wilson carrying the slogan of "making the world safe for democracy". He devised a peace plan of

Fourteen Points. In 1918 Germany launched a spring offensive which failed, and as the allies counter-attacked and more millions were slaughtered, Germany slid into

revolution, its interim government suing for peace on the basis of Wilson's Fourteen Points. Europe lay in ruins, financially, physically, psychologically, and its future with the arrangements of the

Versailles conference in 1919.

John Maynard Keynes was the representative of

Her Majesty's Treasury at the conference and the most vocal critic of its outcome.

[edit] John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) was born in Cambridge, educated at

Eton and supervised by both

A. C. Pigou and

Alfred Marshall at

Cambridge University. He began his career as a lecturer, before working in the British government during the Great War, and rose to be the British government's financial representative at the

Versailles conference. His observations were laid out in his book

The Economic Consequences of the Peace[83] (1919) where he documented his outrage at the collapse of the Americans' adherence to the

Fourteen Points[84] and the mood of vindictiveness that prevailed towards Germany.

[85] Keynes quit from the conference and using extensive economic data provided by the conference records, Keynes argued that if the victors forced

war reparations to be paid by the defeated Axis, then a world financial crisis would ensue, leading to a second world war.

[86] Keynes finished his treatise by advocating, first, a reduction in reparation payments by Germany to a realistically manageable level, increased intra-governmental management of continental coal production and a free trade union through the

League of Nations;

[87] second, an arrangement to set off debt repayments between the Allied countries;

[88] third, complete reform of international currency exchange and an international loan fund;

[89] and fourth, a reconciliation of trade relations with Russia and Eastern Europe.

[90]

The book was an enormous success, and though it was criticised for false predictions by a number of people,

[91] without the changes he advocated, Keynes' dark forecasts matched the world's experience through the

Great Depression which ensued in 1929, and the descent into a new outbreak of war in 1939. World War I had been the "war to end all wars", and the absolute failure of the peace settlement generated an even greater determination to not repeat the same mistakes. With the defeat of

fascism, the

Bretton Woods conference was held to establish a new economic order. Keynes was again to play a leading role.

[edit] The General Theory

The title page to Keynes'

General Theory.

During the Great Depression, Keynes had published his most important work,

The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936). The depression had been sparked by the

Wall Street Crash of 1929, leading to massive rises in unemployment in the United States, leading to debts being recalled from European borrowers, and an economic domino effect across the world. Orthodox economics called for a tightening of spending, until business confidence and profit levels could be restored. Keynes by contrast, had argued in

A Tract on Monetary Reform (1923) that a variety of factors determined economic activity, and that it was not enough to wait for the long run market equilibrium to restore itself. As Keynes famously remarked,

...this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again.

[92]

On top of the

supply of money, Keynes identified the

propensity to consume, inducement to invest, the marginal efficiency of capital, liquidity preference and the multiplier effect as variables which determine the level of the economy's output, employment and level of prices. Much of this esoteric terminology was invented by Keynes especially for his

General Theory, though some simple ideas lay behind. Keynes argued that if

savings were being kept away from

investment through

financial markets, total spending falls. Falling spending leads to reduced incomes and unemployment, which reduces savings again. This continues until the desire to save becomes equal to the desire to invest, which means a new "equilibrium" is reached and the spending decline halts. This new "equilibrium" is a depression, where people are investing less, have less to save and less to spend.

Keynes argued that employment depends on total spending, which is composed of consumer spending and business investment in the

private sector. Consumers only spend "passively", or according to their income fluctuations. Businesses, on the other hand, are induced to invest by the expected rate of return on new investments (the benefit) and the rate of interest paid (the cost). So, said Keynes, if business expectations remained the same, and government reduces interest rates (the costs of borrowing), investment would increase, and would have a multiplied effect on total spending.

Interest rates, in turn, depend on the quantity of money and the desire to hold money in bank accounts (as opposed to investing). If not enough money is available to match how much people want to hold, interest rates rise until enough people are put off. So if the quantity of money were increased, while the desire to hold money remained stable, interest rates would fall, leading to increased investment, output and employment. For both these reasons, Keynes therefore advocated low interest rates and easy credit, to combat unemployment.

But Keynes believed in the 1930s, conditions necessitated public sector action. Deficit spending, said Keynes, would kick-start economic activity. This he had advocated in an open letter to U.S. President

Franklin D. Roosevelt in the

New York Times (1933). The

New Deal programme in the U.S. had been well underway by the publication of the

General Theory. It provided conceptual reinforcement for policies already pursued. Keynes also believed in a more egalitarian distribution of income, and taxation on

unearned income arguing that high rates of savings (to which richer folk are prone) are not desirable in a developed economy. Keynes therefore advocated both monetary management and an active fiscal policy.

[edit] Keynesian economics

During the Second World War, Keynes acted as advisor to

HM Treasury again, negotiating major loans from the US. He helped formulate the plans for the

International Monetary Fund, the

World Bank and an

International Trade Organisation[93] at the

Bretton Woods conference, a package designed to stabilise world economy fluctuations that had occurred in the 1920s and create a level trading field across the globe. Keynes passed away little more than a year later, but his ideas had already shaped a new global economic order, and all Western governments followed the Keynesian prescription of deficit spending to avert crises and maintain full employment.

One of Keynes' pupils at Cambridge was

Joan Robinson, who contributed to the notion that

competition is seldom perfect in a market, an indictment of the theory of markets setting prices. In

The Production Function and the Theory of Capital (1953) Robinson tackled what she saw to be some of the circularity in orthodox economics. Neoclassicists assert that a competitive market forces producers to minimise the costs of production. Robinson said that costs of production are merely the prices of inputs, like

capital. Capital goods get their value from the final products.

And if the price of the final products determines the price of capital, then it is, argued Robinson, utterly circular to say that the price of capital determines the price of the final products. Goods cannot be priced until the costs of inputs are determined. This would not matter if everything in the economy happened instantaneously, but in the real world, price setting takes time – goods are priced before they are sold. Since capital cannot be adequately valued in independently measurable units, how can one show that capital earns a return equal to the contribution to production?

Piero Sraffa came to England from

fascist Italy in the 1920s, and worked with Keynes in Cambridge. In 1960 he published a small book called

Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities, which explained how technological relationships are the basis for production of goods and services. Prices result from wage-profit tradeoffs, collective bargaining, labour and management conflict and the intervention of government planning. Like Robinson, Sraffa was showing how the major force for price setting in the economy was not necessarily market adjustments.

[edit] The "American Way"

After World War II, the United States had become the pre-eminent global economic power. Europe and the Soviet Union lay in ruins and the

British Empire was at its end. Until then, American economists had played a minor role. The

institutional economists had been largely critical of the "American Way" of life, especially regarding

conspicuous consumption of the

Roaring Twenties before the

Wall Street Crash of 1929. After the war, however, a more orthodox body of thought took root, reacting against the lucid debating style of Keynes, and re-mathematizing the profession. The orthodox centre was also challenged by a more radical group of scholars based at the University of Chicago. They advocated "liberty" and "freedom", looking back to 19th century-style non-interventionist governments.

[edit] Institutionalism

Thorsten Veblen came from a Norwegian immigrant family in rural mid-western America.

Thorsten Veblen (1857–1929), who came from rural mid-western America and worked at the

University of Chicago, is one of the best known early critics of the "American Way". In

The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) he scorned

materialistic culture and wealthy people who

conspicuously consumed their riches as a way of demonstrating success and in

The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904) Veblen distinguished production for people to use things and production for pure profit, arguing that the former is often hindered because businesses pursue the latter. Output and technological advance are restricted by business practices and the creation of monopolies. Businesses protect their existing capital investments and employ excessive credit, leading to depressions and increasing military expenditure and war through business control of political power. These two books, focusing on criticism first of

consumerism, and second of profiteering, did not advocate change. However, in 1911, Veblen joined the faculty of the

University of Missouri, where he had support from

Herbert Davenport, the head of the economics department. Veblen remained at

Columbia, Missouri through 1918. In that year, he moved to New York to begin work as an editor of a magazine called

The Dial, and then in 1919, along with

Charles A. Beard,

James Harvey Robinson and

John Dewey, helped found the New School for Social Research (known today as

The New School). He was also part of the

Technical Alliance,

[94] created in 1919 by

Howard Scott. From 1919 through 1926 Veblen continued to write and to be involved in various activities at The New School. During this period he wrote

The Engineers and the Price System (1921).[95]

John R. Commons (1862–1945) also came from mid-Western America. Underlying his ideas, consolidated in

Institutional Economics (1934) was the concept that the economy is a web of relationships between people with diverging interests. There are monopolies, large corporations, labour disputes and fluctuating business cycles. They do however have an interest in resolving these disputes. Government, thought Commons, ought to be the mediator between the conflicting groups. Commons himself devoted much of his time to advisory and mediation work on government boards and industrial commissions.

The

Great Depression was a time of significant upheaval in the States. One of the most original contributions to understanding what had gone wrong came from a

Harvard University lawyer, named

Adolf Berle (1895–1971), who like

John Maynard Keynes had resigned from his diplomatic job at the

Paris Peace Conference, 1919 and was deeply disillusioned by the

Versailles Treaty. In his book with

Gardiner C. Means,

The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932), he detailed the evolution in the contemporary economy of big business, and argued that those who controlled big firms should be better held to account.

Directors of companies are held to account to the

shareholders of companies, or not, by the rules found in

company law statutes. This might include rights to elect and fire the management, require for regular general meetings, accounting standards, and so on. In 1930s America, the typical company laws (e.g. in

Delaware) did not clearly mandate such rights. Berle argued that the unaccountable directors of companies were therefore apt to funnel the fruits of enterprise profits into their own pockets, as well as manage in their own interests. The ability to do this was supported by the fact that the majority of shareholders in big

public companies were single individuals, with scant means of communication, in short, divided and conquered. Berle served in President

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration through the depression, and was a key member of the so-called "

Brain trust" developing many of the

New Deal policies. In 1967, Berle and Means issued a revised edition of their work, in which the preface added a new dimension. It was not only the separation of controllers of companies from the owners as shareholders at stake. They posed the question of what the corporate structure was really meant to achieve.

Stockholders toil not, neither do they spin, to earn [dividends and share price increases]. They are beneficiaries by position only. Justification for their inheritance... can be founded only upon social grounds... that justification turns on the distribution as well as the existence of wealth. Its force exists only in direct ratio to the number of individuals who hold such wealth. Justification for the stockholder's existence thus depends on increasing distribution within the American population. Ideally the stockholder's position will be impregnable only when every American family has its fragment of that position and of the wealth by which the opportunity to develop individuality becomes fully actualized.

[96]

[edit] John Kenneth Galbraith

After the war,

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) became one of the standard bearers for pro-active government and liberal-democrat politics. In

The Affluent Society (1958), Galbraith argued voters reaching a certain material wealth begin to vote against the common good. He argued that the "

conventional wisdom" of the conservative consensus was not enough to solve the problems of social inequality.

[97] In an age of big business, he argued, it is unrealistic to think of markets of the classical kind. They set prices and use

advertising to create artificial demand for their own products, distorting people's real preferences. Consumer preferences actually come to reflect those of corporations—a "dependence effect"—and the economy as a whole is geared to irrational goals.

[98] In

The New Industrial State Galbraith argued that economic decisions are planned by a private-bureaucracy, a

technostructure of experts who manipulate

marketing and