Reference is made to Transfinancial Economics RS

Economic theory continues to evolve as it always has. That is partly because the real world economy is itself continuously evolving. But it is also partly because economic theories are far from perfect, but are retained till something better comes along.

Monetary theory is a highly pertinent example right now, given the evolving role of money. As a means of exchange, it has long been reduced to the role of lubricant for relatively minor transactions, with further reduced usage of notes and coin being trialled during the coronavirus lockdown. As a store of value it has long been outperformed by many alternatives of varying security from property to financial speculation. And its lasting function as a unit of exchange is now largely maintained in electronic form enabling further possibilities.

Neoclassical economic theory emerged in mid 19th century as the inadequate but mathematical expression of self-interest maximising humans, profit maximising businesses and efficient markets free from government regulation which the theory promised would be no longer subject to booms and slumps.

That was the context in which monetary theory was given its first coherent expression by Irving Fisher in early 20th century. It was in the form of a simple equation of exchange: MV=PT, where M is the quantity of money, V the velocity of its circulation, P the overall level of prices and T the volume of transactions taking place in the given time period. While the equation is a truism and identifies macroeconomic quantities, their content is largely immeasurable and its various interpretations susceptible to simplistic political debate.

Fisher became notorious for his repeated assertion that the stock market had reached ‘a permanently high plateau’. That was just before the 1929 Wall Street Crash, which was followed by the Great Depression, imposed and prolonged by the continued focus on M with policies of austerity. That was only ended by Roosevelt’s relaxing austerity and focusing on V with publicly funded New Deal job creation schemes aimed at putting money into the hands of the poor, who had no choice but to spend it immediately for their survival, thus increasing V and so generating further economic recovery.

The 1970s stagflation was observed by Piatier as having been caused by OPEC’s 400% oil price rises and the stagnation arising from the maturing and decline of 2nd industrial revolution industries.[i] But neoclassical theorists argued stagflation to be the failure of Keynesian economics, thus enabling monetary theorists to resume control. But after two decades of application, even leading quantity advocate Milton Friedman admitted the theory had largely failed.[ii]

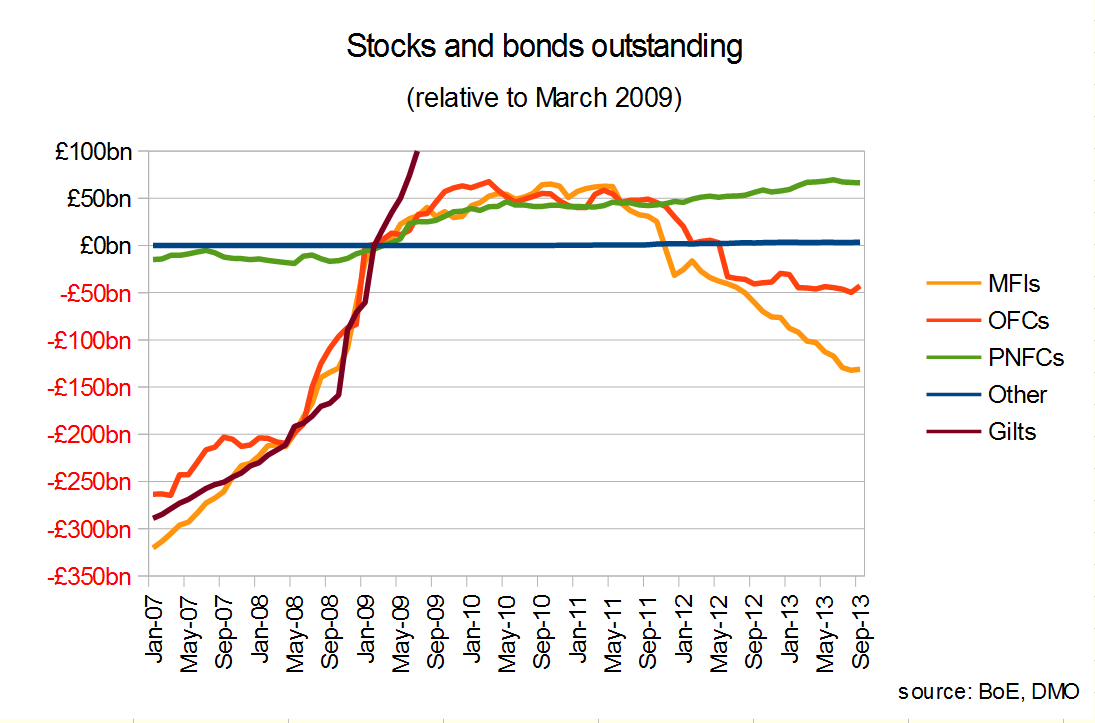

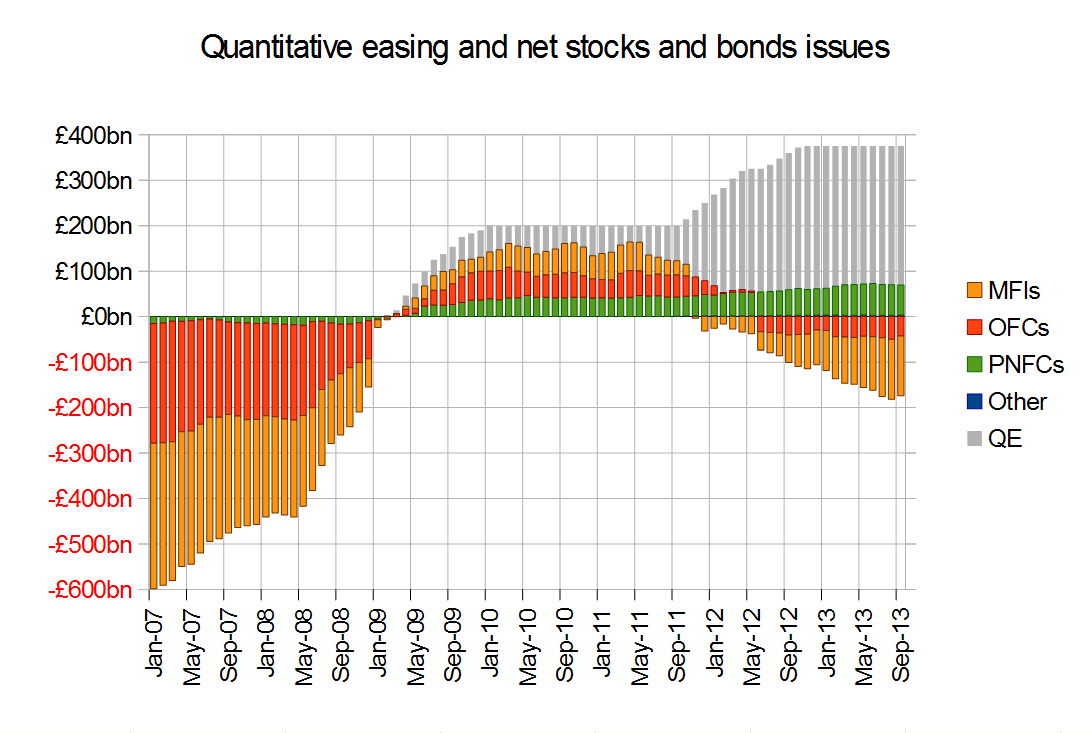

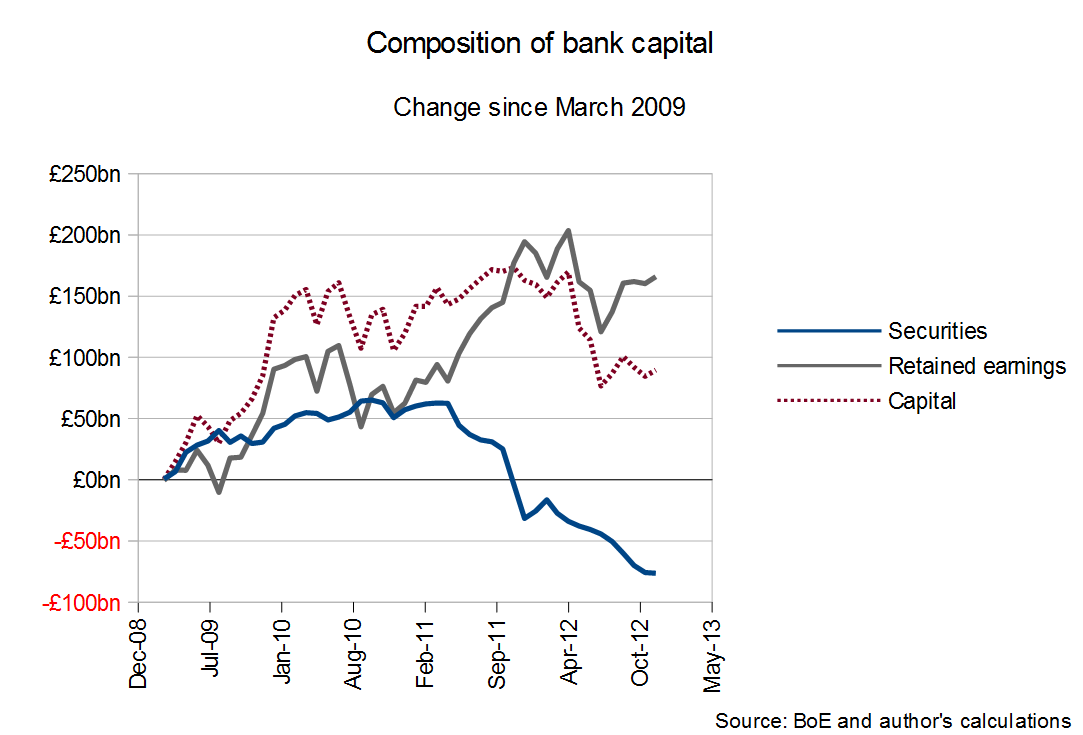

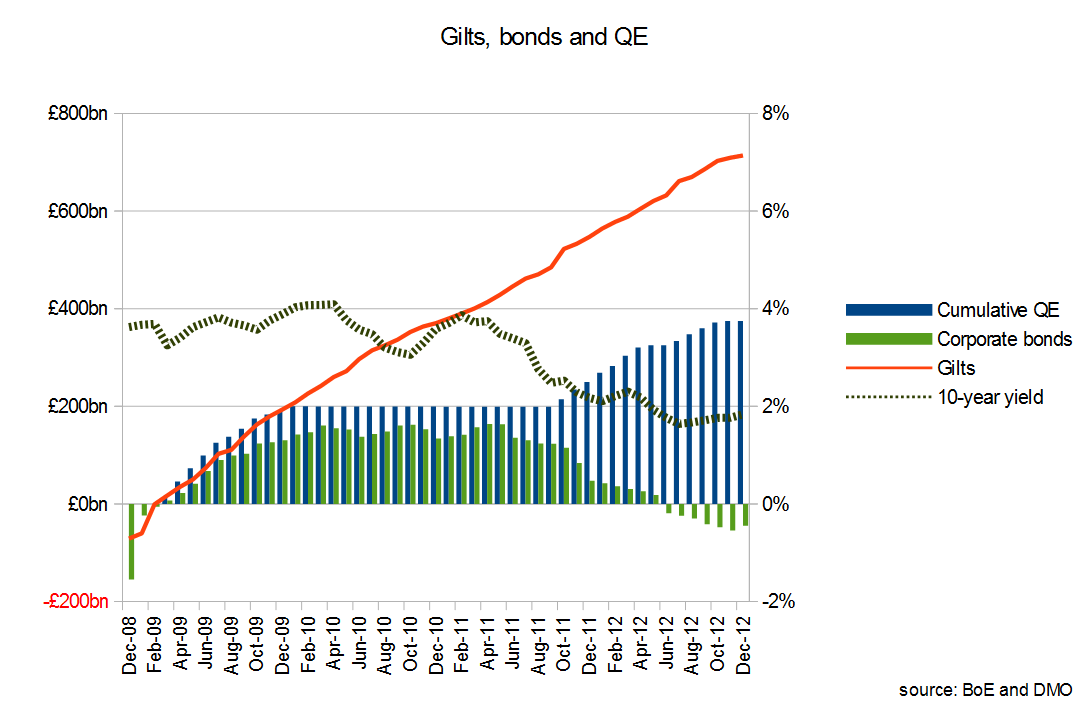

The lessons of 1929 had been set aside and forgotten as demonstrated by the relearning experience of the early 21st century, a period referred to as ‘the great moderation’ for which both politicians and economists at the time took credit. That was just before the 2008 crash, which was followed by a decade of austerity in the real economy, which produced only disappointing results, despite massive Quantitative Easing (QE) for the financial economy banking sector – an estimated $14trillion worldwide. [iii]

That is the context in which Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) emerged, taking account of the limitations of the former theory as well as the evolving possibilities of money itself. MMT explains how a government that issues its own currency, can control and guide its economic growth absolutely without monetary constraint. That must be the holy grail of modern economy. It does so by promoting growth when needed by increasing the quantity of money in circulation. It could also slow growth by increasing taxation if inflationary pressures threatened to exceed what is advisable. Control of money supply and taxation can both be selective so that the direction of economic growth can also be set. The avoidance of booms and slumps is thus held to be firmly within the grasp of MMT competent governments. The validity of such assumptions will become apparent over the next few years and hopefully it won’t simply be a repeat of the 1929/2008 learning experiences.

Within that broad model, the explosion of new technologies is enabling governments and central banks access to many more detailed control mechanisms which MMT can accommodate. It is a highly dynamic situation in which MMT will continue to develop or could even be replaced by alternative theoretical approaches. One such, currently being promulgated, is Transfinancial Economics (TFE), which takes fuller account of the technological possibilities of developing QE for the global economy.

At this point in time, the possibilities of economic theory, notably of MMT, appear immense, but unpredictable. As always, the theory is underwritten by political considerations which were previously focused on the M-V dichotomy.

Now, the extreme possibilities of new technologies, make the Real and Financial economic divide absolutely crucial. The Real Economy is what could produce the needs and wants of everyday life for all people within an environmentally sustainable context. The Financial Economy was initially established to raise the finance for the canals, mills, factories and railways of the first industrial revolution. But since then it has found easier ways of making faster returns than paying for those Real Economy activities. So the Financial Economy has become predatory on the Real by a variety of means, including a process of increasingly sophisticated Merger and Acquisition (M&A) followed by systematic asset stripping and closure of Real Economy organisations.

It is a process which is ignored since the distinction between the Real and the Financial Economies is not made, a fact celebrated by the simultaneous combination of austerity and QE, symbolic of the global combinations such as tax haven corruptions and the climate crisis.

That Real-Financial dichotomy, so vital to Remaking the Real Economy, is completely ignored by economic theory, including MMT. In orthodox measures such as GDP, a $ is a $, whether it is earned through care home services, bets on the financial casino or prostitution.

However, MMT controls enable both money supply and taxation to be selective, so that the direction of economic progression could be focused on the Real Economy making the financial sector resume its former more restrained role as supportive provider of finance.

Moral philosopher Adam Smith started his inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations with observation of real economic activity (pin making), rather than theoretical argument. There was no theory at the time. Real economic activity clearly didn’t require a theory. Today, further progression without detruction might be better achieved if freed from theoretical constraints and diktats.

[i] Piatier, A., (1984), ‘Barriers to Innovation’, London: Francis Pinter.

[ii] Friedman, M., (2003), in interviews with Joel Bakan for the documentary film ‘The Corporation’, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y888wVY5hzw [accessed 10.January 2020].

[iii] Martin, F., (2014), Money: the Unauthorised Biography, London: Vintage Random House.